![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Frontiers—Then and Now

One meaning of the word frontier is a border between places. But those borders can be very different at different times.

Astronaut Dr. Story Musgrave of Kentucky first went into space in 1983. Though he was born outside the state, he learned to fly in Lexington and considered Kentucky his home. He flew on the space shuttle a total of six times, during which he helped repair a space telescope and even walked in space. When he retired, no other person had taken more space flights.

Musgrave was not the only astronaut from Kentucky. Born in Russellville, Terry Wilcutt went to high school in Louisville and got a college degree in Bowling Green. He taught math in high school for a time, then became a space shuttle pilot and participated in four flights. On one, he linked up with the space station.

Both Musgrave and Wilcutt traveled thousands of miles in just a few days. Both saw things that few others had seen. Both experienced a sense of wonder as they left their world for the unknowns of space. But when they faced that unknown future and the frontier of space, they were simply doing what humans have done for thousands of years.

Astronaut Terry Wilcutt. (Courtesy of the Kentucky Library, Western Kentucky University)

How did the first human who stepped on the soil of what is now Kentucky feel? Exactly when that event happened, and who that person was, are unknown. But that first person (one of a group called Indians or Native Americans) started the process of people living in Kentucky—and it still goes on. The first Kentuckian could travel only a few miles on foot each day. Yet as that person looked out over the untouched land, he or she likely felt much the same way those astronauts felt many thousands of years later. That person saw a new place that no one else had ever seen. That man or woman faced a new frontier. That person looked to a fresh future.

Many, many centuries later, people from Europe arrived at what, to them, was the New World, and they called it America. Think of how it would be today if astronauts in a space shuttle suddenly came upon a new, previously unknown planet and found that humans were already living on it. Such feelings of discovery and awe the Europeans experienced in America. They found humans they did not know even existed. The Indians, of course, had the same reaction, for these people from across the ocean were new to them too.

European explorers soon made their way to Kentucky and found a land that filled them with excitement. Like the Indians before them, they wanted to live there. They also sought a new life on this new frontier. Although living thousands of years apart, the first Indians, the first European explorers, and even the present-day astronauts from Kentucky all shared the same human feelings about the places they saw.

Today, if people want to travel to places that no one has seen before, they may have to go into space, as astronauts Musgrave and Wilcutt did. But many frontiers still exist on earth, and the spirit of those earlier people remains alive today. After all, change happens all the time. Our future may involve another meaning of the word frontier. It can also mean discovering new learning and the outer boundaries of knowledge. Our future frontiers may be frontiers of the mind. People may make discoveries in science or medicine, invent new ways of doing things, write books that cause people to think in different ways, or so much more. New frontiers still await present-day explorers.

The Past

People who study the past are explorers too. Similar to those who came to Kentucky many years ago, historians want to discover new things. Like detectives trying to solve the mysteries of history, they seek to uncover the hidden past.

But why? Why is history important? First of all, knowing what other people did means that current generations do not have to relearn everything. They do not have to repeat earlier mistakes and can follow the example of what worked for others. In the end, the historical record remains the only guide to how humans acted.

If people got up each morning and did not know where to go or what to eat, they would have to learn those things over and over again. They would not get much done and would make many mistakes before discovering what they needed to know. If the people living in a state or a nation do not know their history, they have to relearn all of life's lessons. That is why history is important.

History is about real people and real events. Sometimes individuals make mistakes; sometimes they act heroically and courageously in matters big and small. Those actions and those lives can be models for today. History is not just about the past; it is also about the future.

Writing about the Past

Everyone can be a historian. If you wanted to write a history of your grandparents, for example, you might first talk to them and let them tell the story of their lives—an oral history. Then you could ask other people what they know about your grandparents. You might go through family photographs or even old letters that had been saved. Reading historical city and county newspapers might reveal stories about your grandparents' past. School yearbooks could provide additional information about them. Any land or houses they bought would be listed in records in the courthouse. Finally, everything you found out could be written down as their history, their record of life on this earth. In doing those things, you would be acting as a historian, solving mysteries and explaining your grandparents' lives to others. And in the end, you would likely learn things you did not know before—about your grandparents and about yourself.

But what happens when no letters, newspapers, or other written sources are available? How can people re-create the elusive past in that case? In fact, that is the situation for most of the years that humans have lived in Kentucky. Trying to tell the story of those times becomes much more difficult. Without written records and people to interview, how can we find out about the people of the past?

Archaeologists try to find answers by studying ancient people and looking at what they left behind—stone tools, bits of pottery, pieces of clothing, burial places, skeletons, and even trash pits. If someone looked at a modern family's trash, what could they find out about them? By examining the trash of the past, archaeologists can discover what people ate, based on the animal bones or shells they threw away. They could uncover bits of broken jars and be able to determine how the people stored food and other things. They might find old pieces of arrows and understand how the ancient people made weapons. Such records can suggest how people lived thousands of years ago. What, then, do we know about the first people in Kentucky?

Native Americans in Kentucky

Native Americans (or American Indians) are not really native to America. They, too, came as immigrants. Thousands of years ago, when the land and oceans had different configurations, people from Asia could walk across a land bridge to Alaska. From there they slowly spread over America. It is possible that some also came by small boats across the Pacific Ocean. Native Americans traveled to America, then, just as other people did much later.

These new people found themselves in a new land filled with animals that they could hunt—and animals that could hunt them, too. Eventually, one Indian—or perhaps a whole family—came to what we now call Kentucky, and the first humans walked this land. That event probably happened at least 12,000 years ago. If one generation covers 20 years, then 600 generations of American Indians lived and died here before the first European explorers even arrived in America. In contrast, only a dozen or so generations have lived in Kentucky since written histories have existed. To put it another way, if every inch on a six-inch line stands for 2,000 years of history, then Europeans have been in Kentucky only one-eighth of an inch on that scale—not very long.

Change takes place over time, and archaeologists have divided those 12,000 years into four different periods, each with its own characteristics.

Paleo-Indians, 10,000 to 8000 B.C.

Paleo-Indians came to Kentucky some 12,000 years ago, in 10,000 B.C. or earlier. At that time, ice covered most of the northern part of the United States, and Kentucky had a much colder climate than it does today. Its trees resembled those in the far north today, and large lakes covered parts of the land.

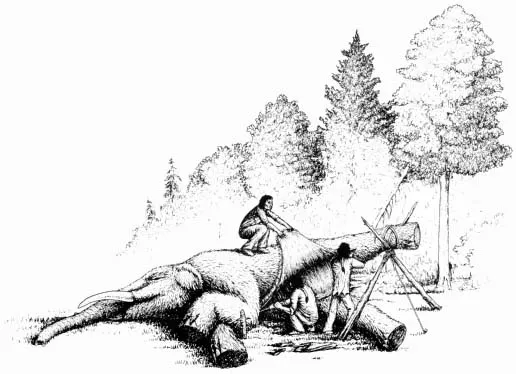

Little is known about the Native Americans who walked the land then. Now-extinct animals, including huge mammoths and mastodons, roamed nearby. The Indians hunted some for food, using sharpened stone points on spears. They stayed in small camps of a few dozen people but built no houses; they used rock shelters or anything else they could find in nature. Overall, they lived hard, simple, short lives. Probably no more than 5,000 people called Kentucky home during this period.

Native Americans hunted the mammoths that roamed Kentucky, using the skin for protection from the cold and the meat for food. (Kentucky Heritage Council poster titled “Kentucky before Boone”)

Although their lives differed greatly from ours, they had the same human feelings. They saw people being born and others dying. They loved and hated; they understood pleasure and pain. They laughed and cried, and they knew happiness and sorrow. They were not all alike; individual differences existed, just as today. Some had different ideas or spoke different languages. Sometimes they lived at peace with one another; at other times they fought. Not much is known about them, but they did start the process of humans living in Kentucky.

Archaic Period, 8000 to 1000 B.C.

The Archaic period, which lasted about 7,000 years, represents the longest period of Native American life in Kentucky. During that time, the land changed as the ice age ended. Inland seas disappeared, modern rivers flowed, the population increased, and people moved less. For food they killed deer, elk, beavers, birds, and turtles. They also gathered nuts and ate river mussels.

The Archaic people invented new weapons for hunting. The atlatl allowed them to throw their spears a greater distance. They made stone axes as well and used them to build dugout canoes.

Near the end of the Archaic period, a small shift took place, but it was one that would mark a major change over the years. When the American Indians in Kentucky began to grow squash—both for food and as containers—that marked the beginning of farming and a new way of life.

Woodland Period, 1000 B.C. to A.D. 1000

For 2,000 years, change took place gradually. People still mostly hunted for food and added only sunflowers and a few other plants to what they grew. But two major inventions did occur—pottery and a new weapon.

Woodland Indians in the eastern and central parts of Kentucky began making pottery around 1000 B.C. Having bowls and pots allowed them to cook directly over a fire. In that simple society, however, it took another 500 years for pottery making to reach parts of western Kentucky. Later, around A.D. 800, a new weapon arrived: the bow and arrow. Use of the bow and arrow spread rapidly, and Native Americans were soon utilizing it for both fighting and hunting.

During this time, the Indians' lifestyle grew increasingly complex. They used axes to cut trees and clear land, which changed their environment. Objects found in burial mounds show that they also had a strong belief in life after death. But the biggest change came at the end of the Woodland period, when Native Americans began to grow maize (corn). Corn, potatoes, tobacco, and tomatoes—all American crops unknown to Europeans—led to the creation of a new farming lifestyle in the next era.

Kentucky Lives: An Indian's Story

His name, if he had one, is lost to history. But more than 2,400 years ago, a Native American man entered Mammoth Cave to dig minerals, unaware that he was working in one of the largest cave systems in the world.

The man got up in the morning, put on a skimpy piece of clothing, and left camp for the cave. He was about fifty-four years old and stood five feet, three inches tall. Perhaps he saw his mate making barrel-shaped pots as he was leaving. Perhaps others who were tending sunflowers in the fields watched him go. That is not known. What is known is that he lit some reeds to use as torches and went three miles into the darkness of Mammoth Cave. He was high on a ledge, digging out minerals and placing them in a pouch, when a rock fell and crushed him. The cool air in the cave preserved his body for centuries. About seventy years ago, some people found his mummified remains. He is a reminder of the present's link to those who lived and died in the past.

Late Prehistoric Period, A.D. 1000 to 1750

Corn-based farming produced more food, which caused a rapid increase in the number of Indians. They built larger villages and formed towns ruled by powerful chiefs. Trade expanded all the way to the Great Lakes. But such growth meant that different groups had more contact with one another, and violence increased.

Differences between the Native Americans within Kentucky became greater as well. In the west, the Mississippian culture consisted of large, walled villages of more than 1,000 people. Tall, flat-topped earthen pyramid platforms and a central, open plaza for sports and other events dominated these v...