![]()

1

China’s Development

as a World Power

Objective Conditions, Strategic

Opportunity, and Strategic Choices

Following the revival of China, four kinds of objections have been raised to the idea of its becoming a world power.

The elephant mentality. According to this viewpoint, it is unrealistic to believe that China can achieve its objective of becoming a world power. “It is impossible for China to catch up with the West, not to mention surpassing it, in the twenty-first century. There is no way to tell whether it will even be able to do so in the twenty-second century. Thus, we ought to jettison the unrealistic objective of overtaking the West.” Internationally, China should not pick fights with the world, and it should not try to become a superpower on a par with the United States. There is no need for it to seek to become a “tiger” like the United States; indeed, since it lacks the capability, this is impossible. Nor should it join the company of the “wolves,” namely, Russia, Japan, and India. Of course, China cannot act like a sheep that others devour. It should be like a gentle elephant that stands apart from the tigers, wolves, and sheep, having no conflict with them, and not contending with them for food.1

The theory of natural growth. This view is that it does not matter whether China wants to develop into a world power. The crucial point is that it needs to develop; its status as a world power will follow naturally. It should not struggle to achieve the status of a world power. When it develops to the level of a world power, sooner or later it will achieve world power status.2

The theory that conditions are lacking. The core argument from this perspective is that China has so many domestic problems and is backward in so many aspects that it presently lacks, and will continue to lack, the qualifications to be a world power. Therefore, there is no point in it even trying. Though it has made great achievements in economic reform since the late 1970s, further reflection indicates that, in spite of its rising status, China lacks three decisive elements necessary to becoming a world power: a favorable security environment, hard military and economic power, and the soft power of politics, society, and ideology.

The theory that China will collapse. In his book The China Dream, Joe Studwell, the editor-in-chief of the U.S. journal The Chinese Economy, stated that the Chinese economy is a mansion constructed on sand.3 Probably the best example of this doom-and-gloom genre is The Coming Collapse of China, by Gordon Chang, who believes that China’s entry into the WTO in 2001 was the starting point of its impending collapse.

None of these viewpoints stands up to scrutiny. Rather, China possesses both the objective conditions and the historical prerequisites necessary to become a world power.

THE OBJECTIVE CONDITIONS AND HISTORICAL PREREQUISITES NECESSARY FOR CHINA TO BECOME A WORLD POWER

China Possesses the Objective Conditions to Become a World Power

We may consider the attributes of a great power with respect to natural geography and economic potential under the following headings:

China is the third largest country in area. Some scholars think that being a world power requires a special sort of territorial foundation; that is, countries aspiring to world power status must be continent-sized powers like Russia, the United States, and China. France, on the fringe of a continent, and island nations like the United Kingdom and Japan do not meet this criterion. This viewpoint is somewhat overstated since history has witnessed a number of world powers—including the earliest world power, the Roman Empire, and the Spanish and Ottoman empires—that were not, in fact, continent-sized land powers. Nevertheless, it remains true that an extensive territory is an important prerequisite to becoming a world power.4

Countries with territories of more than 1 million square kilometers are the largest in the world. There are twenty-eight such countries whose total land mass of 99,680,000 square kilometers represents 74 percent of the world’s total 133,480,000 square kilometers. Among them there are twelve would-be great powers, including Russia (17,070,000), Canada (9,970,000), China (9,600,000), the United States (9,360,000), Brazil (8,510,000), Australia (7,710,000), India (3,280,000), Mexico (1,950,000), Indonesia (1,930,000), Iran (1,640,000), South Africa (1,220,000), and Egypt (1,000,000). Other countries with large territories include Argentina (2,760,000), Kazakhstan (2,710,000), Saudi Arabia (2,150,000), Sudan (2,500,000), Algeria (2,380,000), Libya (1,750,000), Mongolia (1,560,000), Peru (1,280,000), Chad (1,280,000), Niger (1,260,000), Angola (1,240,000), Mali (1,240,000), Columbia (1,130,000), Bolivia (1,090,000), Ethiopia (1,090,000), and Mauritania (1,020,000). The territorial expanses of some large economic powers are as follows: Turkey (770,000), Japan (370,000), Germany (350,000), the United Kingdom (240,000), France (550,000), Italy (300,000), and South Korea (99,000).

China is the most populous country in the world. Countries with populations exceeding 50 million as of 1995 may be counted among those with the largest populations in the world. There are twenty-three such countries, accounting for 4.168 billion, or 74 percent, of the total global population of 5.673 billion. Among them are China (1.3 billion), India (1 billion), the United States (263 million), Indonesia (200 million), Brazil (159 million), Russia (148 million), Japan (125 million), Mexico (92 million), Germany (82 million), Iran (64 million), the United Kingdom (58.5 million), France (58 million), Egypt (58 million), and Italy (57 million). Other countries with large populations include Pakistan (130 million), Bangladesh (120 million), Nigeria (112 million), Vietnam (74 million), the Philippines (69 million), Turkey (61 million), Thailand (58 million), and Ethiopia (56 million). The populations of some economically powerful countries are as follows: Australia (18 million), Canada (29.6 million), Spain (39 million), and South Korea (45 million).

China is the world’s sixth largest economy in terms of GDP. Any country with a GDP that exceeds US$200 billion has the potential to become a world economic power. There were twenty-two such countries in 1997, accounting for US$25.8 trillion of the world’s total GDP of US$29.9 trillion, or 86 percent. These countries are the United States (US$7.69 trillion), Japan (US$4.77 trillion), Germany (US$2.32 trillion), France (US$1.53 trillion), the United Kingdom (US$1.22 trillion), Italy (US$1.16), China (US$1.06), Brazil (US$773 billion), Canada (US$583.9 billion), Spain (US$570.1 billion), South Korea (US$485.3 billion), Russia (US$403.5 billion), the Netherlands (US$402.7 billion), Australia (US$380 billion), India (US$373.9 billion), Mexico (US$348.6 billion), Switzerland (US$313.5 billion), Argentina (US$305.7 billion), Belgium (US$268.4 billion), Sweden (US$232 billion), Austria (US$225.9 billion), and Indonesia (US$221.9 billion).

According to World Bank data published on April 2, 2002, the first twenty-one countries in terms of GDP in the year 2000 are as follows: the United States (US$9.84 trillion), Japan (US$4.84 trillion), Germany (US$1.87 trillion), the United Kingdom (US$1.41 trillion), France (US$1.294 trillion), China (US$1.08 trillion), Italy (US$1.074 trillion), Canada (US$687.8 trillion), Brazil (US$595.4 billion), Mexico (US$574.5 billion), Spain (US$558.5 billion), South Korea (US$457.2 billion), India (US$456.9 billion), Australia (US$390.1 billion), the Netherlands (US$364.8 billion), Argentina (US$284.9 billion), Russia (US$251.1 billion), Switzerland (US$239.7 billion), Sweden (US$227.3 billion), Belgium (US$226.6 billion), and Turkey (US$200 billion). (Austria and Indonesia, which made the list in 1997, had GDPs of US$189 billion and US$153.2 billion, respectively, in 2000.) These twenty-one countries generated US$26.93 trillion of the global GDP of US$31.49, or some 85 percent.5

China is a country with significant political and military power. China is one of five countries to hold permanent seats on the UN Security Council. The other four countries are the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and Russia. These are also the five big nuclear powers. What is more, China has become the third country capable of sending manned craft into outer space.

China Has Sufficient Comprehensive National Strength to Develop into a World Power

The concept of a world power is based on comprehensive national power, not just one or two indicators. Deng Xiaoping pointed out that comprehensive national strength should be viewed in an all-around way. According to research by Chinese and foreign scholars, comprehensive national strength is composed of the following elements. It is the power of a sovereign country, including both hard power, such as economic and military power, and soft power, such as spiritual culture, national historical tradition, and national cohesiveness. National power also includes both present power and potential power.

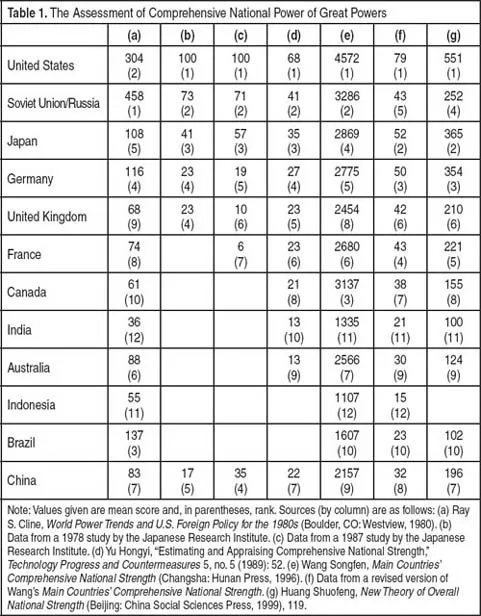

The German scholar William Fuchs of Berlin University, a professor of theoretical physics, is perhaps the earliest Western scholar to study international relations from the perspective of comprehensive national strength. His National Power Equation (1965) incorporated the results of extensive research and computation with various complicated formulas.6

Other scholars before and after him also advanced similar concepts. The U.S. scholar Ray S. Cline is one of the better-known figures in this field. He served as deputy director of the CIA, the head of the Bureau of Intelligence and Research in the State Department, and the director of the Center for Strategic and International Studies at Georgetown University for a long time. He published two books: World Power Assessment in 1975 and World Power Trends and U.S. Foreign Policy for the 1980s in 1980.7 Cline divides national strength into physical and spiritual elements. The physical element is composed of population, territory, GDP, energy, minerals, industrial production, food supplies, trade, and military power. The spiritual element includes strategic intentions and national willpower.

According to a report issued by the Japan Comprehensive Planning Bureau commissioned by the Economic Planning Department, national strength is composed of three capacities: international capacity, survival capacity, and coercive capacity. International capacity includes the economy, monetary power, science and technology, fiscal power, and mobility. Survival capacity includes area, population, resources, national defense, national will, and relations with allies. Coercive capacity includes military power, strategic resources and technology, economic power, and diplomatic power.

The U.S. scholar Nicholas John Spykman listed ten elements of comprehensive national strength: territory, border characteristics, population, raw material, economy and technology, financial power, national homogeneity, social homogeneity, political stability, and public morale. Another prominent international relations specialist, Hans J. Morgenthau, pointed out nine elements of comprehensive national strength: geography, natural resources, industrial capacity, military preparedness, population, national character, national morale, diplomatic skill, and quality of government. Yet other U.S. scholars, Robert Cox and Robert H. Jackson, emphasize five elements: GDP, per capita GDP, population, nuclear capacity, and international prestige.8

Joseph Nye, a former U.S. deputy undersecretary of state and dean of the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, argues that national power is composed of both hard power and soft power. Hard power is the power to control others; it includes basic resources and military, economic, and scientific and technological power. Soft power includes national cohesion, culture, international legitimacy, and participation in the international system.9

Chinese scholars have also expressed their views on this fundamental question. They believe that comprehensive national power means the organic total of all the strength of a sovereign country, including population and natural resources and soft power and hard power. There are several variants of this view.

In the first variant, there are seven elements, namely, natural power, manpower, economic power, scientific and technological power, educational power, national defense power, and political power. In the second variant, there are four elements: basic power (population, resources, national cohesion), economic power (industry, agriculture, science and technology, finances, and business capacity), defense power (strategic resources, technology, military, and nuclear power), and diplomatic power (foreign policy, approaches to dealing with international affairs, fundamental positions, and foreign exchanges and aid). In a third variant, there are eight elements: basic national indicators (territory, geographic location, natural resources, climate, terrain, strategic territory), population, economy, science and technology, defense power, political power, spiritual power, and foreign relations. In a fourth variant, there are seven elements: politics, economy, science and technology, national defense, culture and education, diplomacy, and resources. In a fifth variant, there are ten elements, distributed between hard power and soft power. Hard power here comprises economic power (the foundation), military power (the means of enforcement), and scientific-technological power (the leading force). Soft power is composed of open, stable, enduring, and adaptive domestic political, social, and economic systems; strong cultural, political, moral, and cohesive power; theoretical guidance; strategic insight and diplomatic skill; effective domestic and international management, including effective mobilization of domestic and international resources; well-educated and culturally advanced citizens; and high living standards.10

As may be seen, there are many common elements within these varying definitions of what constitutes comprehensive national strength. Table 1 presents a guide to the views of a number of the aforementioned authors.

My own view is that it is more productive to understand so-called comprehensive national strength as comprising a country’s survival ability, development capacity, and international influence.

Different countries have different requirements for comprehensive national power. If a small country adopts the strategy of allying with a big power, it may be inclined to think that it is not necessary to possess its own military forces because, if something happens, it may not be able to defend itself by relying on its own forces. If it does try to build up its own military to defend itself, it is likely to discover that it lacks the wherewithal to do so. Moreover, if it is attacked by a larger neighbor, it may still be unable to defend itself. For these reasons, I do not propose to discuss the comprehensive national power of middle and small countries.

Furthermore, comprehensive national power has, of necessity, different requirements in different times. Formerly, natural resources, such as land, and the basic necessities of life, including food and minerals, were the basic conditions of comprehensive national power. Nowadays, human resources, that is, women and men with a higher education, have become the decisive element in a country’s total power. For example, combat effectiveness used to be measured by the number of troops and the level of morale. Now, the most important element is the quantity of high-tech weapons and equipment.

Whether a country has the will to achieve global influence is also important in assessing the likelihood of its achieving that influence. If a country lacks the will, it may not regard the possession of such influence as important to it. In the 1920s and 1930s, few Americans put much stock in membership in the League of Nations. In the 1960s, Mao Zedong stated that it did not matter whether China was a member of the United Nations since China itself was like a United Nations of many nationalities. At the time, China was disinclined to take part in or play an active role in international activities. In some cases, the conditions for its participation were lacking; in others, it lacked the will to participate.

Therefore, in this discussion, greater emphasis is placed on what sort of comprehensive national power a would-be or potential great power must possess.

The three dimensions that constitute the comprehensive national strength of any given country can be elaborated as follows.

Survival capacity. The necessities for national survival include territory, geographic location, natural resources, climate, topography, strategic territory, population, national cohesion, nationality structure, economic power, military power, etc. Theorists of the realist school assert that all countries must give top priority to national security. Therefore, each country must possess the necessary survival capacity, including territory, population, natural resources, and requisite economic strength (a certain level of GDP and per capita GDP). The survival capacity requirements of a would-be world power with global influence are much greater than they are for ordinary countries. For example, a country with only 3 or 4 million people and a territory of only several thousand square kilometers cannot become a world power no matter how hard it may try. We can summarize the prerequisites for becoming a world power as follows: a population greater than 50 million, total territory (including territorial waters) of no less than 1 million square kilometers, a GDP ranking within the top thirty, total foreign trade among the top thirty, per capita GDP based on purchasing power of over US$3,000,...