![]()

ONE

MAN-ROOT

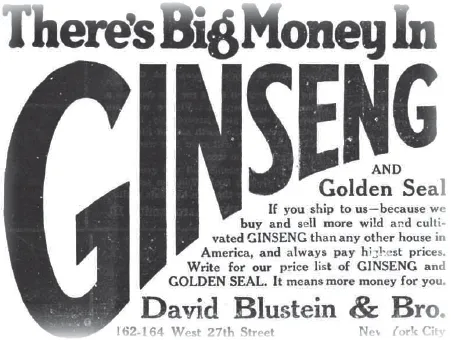

Previous page: This advertisement was published during the first great boom years of American ginseng, in the August 1916 issue of the Ginseng Journal and Goldenseal Bulletin. Courtesy of Lloyd Library and Museum.

In November of 1912, a peculiar little magazine made its first, unheralded appearance. It was the brainchild of an elderly man named Penn Kirk, the owner of a carpet-weaving business in Arrowsmith, Illinois. He served as its editor, publisher, sole reporter, desultory proofreader, subscription agent, advertising salesman, and chief promoter. He called it The Ginseng Journal.

A handful of farmers scattered around the eastern United States had begun experimenting with cultivating the valuable plant as much as thirty years earlier, and by now they figured they were getting it down to a science. Through endless trial and error, they had learned that the seeds needed a year and a half and the sharp cold of winter to germinate, and that the plant flourished best under the canopy of the forest but would grow, grudgingly, under artificial shade. The idea had traveled by word of mouth, until rumors of easy riches from ginseng growing spread from the forests of Maine to the mountains of California. This was when Penn Kirk decided to launch his magazine.

It wasn’t a very impressive debut. The cover of the Ginseng Journal, volume 1, number 1, is adorned only with the subscription price (“Six months 25 cents One year 50 cents”) and a list of advertising rates by the word, inch, or page. Its first two pages contain (crammed between ads for a “bottle clothes sprinkler,” asthma cures, and a magazine called Modern Electrics) recipes for invisible ink and sneezing powder. It isn’t until page five that we reach the heart of the matter. There we read how an Ohio farmer struck it rich: “George Wilson, of the East Pike, Wednesday received a check for $1,102 for the balance of his last crop of the medicinal root just marketed by him in China. Mr. Wilson says he spent only $25 in cultivating the roots sold for this sum. He secured 4,300 per cent on his investment.” With a 1912 dollar the equivalent of $19 today, the fortunate Mr. Wilson had just raked in over $20,000.

Of the sixteen pages in the magazine’s first issue, only two and a half concern ginseng. The rest are a three-page installment of a serial, floating in an ocean of ads for get-rich-quick schemes (compiling mailing lists, agents to sell a “household necessity,” and that perennial favorite, stuffing envelopes). Kirk’s “Talks on Ginseng Raising” are heavy on enthusiasm, though skimpy on facts: “Ginseng,” he declares, “is of slow growth, and therefore all the more valuable. A tree is also of slow growth, but timber is valuable anywhere you use it. When you consider how quickly you can begin to sell seeds from your seng, and how rapidly the price advances for the plants as they get older there is no time that they depreciate in value. Bankers will loan money on a growing crop of ginseng, and your credit is strengthened with them as soon as they know you are carefully growing it.” Logic and rhetoric were not his strong suits.

But the magazine took off. The second issue is printed on lovely pink paper, and its cover bears a photo of an enormous mound of harvested ginseng root and the slogan, “Devoted to the Interests of Ginseng and Golden Seal Growers” (goldenseal is a less valuable herb still cultivated alongside ginseng). In his Ginseng Talk, Kirk answers a couple of readers’ letters asking about preparing the soil (“First clean it well and next spade it well. Third drain it well.”) and the issue of starting from seed vs. buying plants (“Let me say that if you have ready money never think about spending the time fooling with seeds.”). The magazine discusses the process of stratifying seeds, before moving on to a page on goldenseal, an article on the history of the Christmas tree, two page-long poems, a short story, and the inevitable ads for “How to go on the Stage,” a home-study taxidermy course, starting one’s own tooth-powder manufacturing business, and something called the “Endless Dime Scheme” (for which, suspiciously, you are to send ten cents).

Penn Kirk lived in a vastly different America, one populated by fewer than 100 million people, a land in which many had never been farther from home than they could travel in a horse and wagon. Though automobiles were becoming more common—more than half a million of them were already on the road—there were very few places to drive them. Not a single mile of paved road existed outside the major cities, and the Lincoln Highway, the first all-weather road across the United States, was still nothing more than a very hypothetical line across the map. Covering a distance of ten miles could be a day’s work on the rutted, impassible roads, where auto and horse-cart alike could bury themselves to the axles in mud after a hard rain.

And yet, in the forests of Minnesota, in the hills and hollows of the Tennessee mountains, in backyard gardens in quiet Pennsylvania towns, farmers were growing a plant for export to a dimly known country halfway around the world—imperial China. How this came about is an implausible tale that depends, ultimately, on the scientific curiosity of two men in the early 1700s. They were both French Jesuit priests, and they never met each other.

The Society of Jesus, the official name of the Jesuit order, was founded in 1534 by St. Ignatius of Loyola to bring new life to the Catholic Church following the Protestant Reformation. These highly educated priests had as their mission education and scholarship, and often focused on converting the elite of the countries they visited to Christianity. One Jesuit strategy was to use Western science to perform services for the local rulers. It was with this aim that a group of Jesuits was dispatched to China to compile the country’s first accurate atlas for Emperor Kang Hsi. Among them was the French mathematician Father Pierre Jartoux. Along with his surveying work, Jartoux compiled reports on things Chinese for the use of his order. In 1711, he submitted a report to the Jesuits’ Procurator General entitled “The Description of a Tartarian Plant, called Gin-seng, with an Account of its Virtues.”

These virtues, he believed, were many. “Nobody can imagine that the Chinese and Tartars would set so high a value upon this root if it did not constantly produce a good effect. . . . It is certain that it subtilizes, increases the motion of, and warms the blood, that it helps the digestion and invigorates in a very sensible manner.” He tried it himself as a remedy for exhaustion, and found that “an hour later I was not the least sensible of any weariness.”

Jartoux, a meticulous scientist, went on to record in careful detail how the Chinese prepared the plant by slicing and boiling it. He described the soil and climate conditions that favor its growth, and the harsh life faced by wild ginseng hunters in Manchuria: “They carry with them neither tents nor beds, everyone being sufficiently loaded with his provision, which is only millet parched in an oven, upon which he must subsist all the time of his journey. So that they are constrained to sleep under trees, having only their branches and barks, if they can find them, for their covering.”

But most importantly, Jartoux gave a finely observed description of the plant’s appearance and growth habits, and accompanied it with a precise scientific drawing along with measurements. Though Europeans had been aware of ginseng since the time of Marco Polo’s first descriptions of China, no one knew the plant’s precise nature, what the Chinese used it for, or where it grew. Father Jartoux’s report was so invaluable that it was later translated and published in 1713 by the Royal Society of London, the preeminent scientific organization of the day.

But that was not where the second Jesuit learned of it. Father Joseph Francois Lafitau was a missionary to the Iroquois of Canada, likely a far less prestigious assignment than that of cartographer to the Chinese Emperor. He arrived in Quebec in 1715 to work at the Jesuit mission of St. Francis Xavier. Every year, his order would send out to its missionaries a collection of letters from their Jesuit brothers at work in other countries, containing practical and scientific information that could prove useful in their labors.

Father Lafitau was particularly interested in medicine. “In order to announce the truths of our religion to uncivilized nations,” he wrote in a memoir, “and make them taste of a morality very opposed to the corruption of their hearts, we first have to win them over, and to insinuate ourselves into their spirits by becoming necessary to them. Several of our missionaries have succeeded in different places because they have a certain talent for medicine. I know that while working to cure the ills of the body they have been lucky enough in some cases to open the eyes of the soul.” This, he decided, would be an excellent approach to use with the Iroquois, and he applied himself diligently to the study of medicine. When Father Jartoux’s report on ginseng arrived in his bundle of missionary letters, he decided it sounded very promising indeed. A plant that powerful could help win any number of souls for Jesus.

Studying Jartoux’s description of the soil and climatic conditions favorable to ginseng, he realized that his region of Canada, between Montreal and Ottawa, fit the bill perfectly. But the native people of the area didn’t recognize the plant from the picture he showed them, and he spent three months combing the woods for it with no success. Finally, in late summer, a cluster of crimson berries caught his eye in the woods near a house that he was building. He showed the plant to a woman at the mission, and she recognized it as one of their minor remedies.

Immediately, Lafitau sent some samples of ginseng off to a plant expert in Quebec City, who agreed that it must be a form of Jartoux’s plant. He then dispatched a report and samples to Paris. But saving souls with ginseng soon became a secondary consideration, as the French quickly grasped the commercial importance of the plant. Not long afterward, a trial shipment of ginseng roots was sent from Montreal to China. When the ship finally returned, after long months, the news was good. The Chinese had received the new form of ginseng enthusiastically, and deduced that its medicinal properties were somewhat different from those of the Asian root. Mission Indians were sent out in the woods to harvest the wild plant for shipment halfway around the world.

Father Lafitau returned to France in 1718 to attend to business, but he never went back to his mission in Quebec. Though he wanted to return to Canada, his superiors instead gave him the position of Procurator for all the missions in Canada. He later wrote several books about the Canadian Indians. It is not recorded whether ginseng ever brought any of their souls to the True Faith.

But why didn’t China simply grow its own ginseng? In a word, it couldn’t—and still can’t. Ginseng is native to cool, shady forests, and requires deep soil made of centuries of decomposed leaf litter. Without the nutrients from the leaves, ginseng fails to flourish, or simply won’t come up at all. More than a millennium ago, the pressure of China’s burgeoning population brought the destruction of its last remaining temperate forest. Wild ginseng’s habitat in China has been eradicated, and cannot be rebuilt, leaving them with no choice but to obtain it from Korea, Manchuria—or North America.

The ginseng trade in Canada quickly boomed. By 1720, ginseng was being exported to China on consignment by the Company of the Indies, a French trading company. Native Americans and white trappers combed the forests for it. Fur traders turned to it as a sideline, dealing in pelts in the winter and spring, and ginseng in the summer and fall—a pattern that continues in Appalachia to this day.

Gradually, the hunt for ginseng spread southward throughout the plant’s natural range, and on into what is now the United States. In colonial times, the Catskill and Allegheny Mountains were prime hunting grounds, and Albany, New York, was an important trading center.

Daniel Boone was one notable ginseng hunter. While exploring and hunting west of the mountains in the newfound frontier of Kentucky, he gathered ginseng roots, along with the furs that were the mainstay of his livelihood. But as with just about every other facet of his life, his ginseng hunting was dogged with almost relentless bad luck. By one account, Boone had spent a year amassing a huge stockpile of roots at a time when the price was quite favorable, and loaded it on a keel boat to take it to market on the Ohio River. While attempting the cross a strong current, the boat overturned, soaking its cargo. He had to wait for help to come from three miles away, by which time the roots were mostly ruined. He attempted to dry the ginseng quickly in the sun—further damaging it—and ended up selling the roots for a pittance.

Some of these early ginseng tales, however, have to be taken with a grain of salt. Most writers quote each other and claim that Boone’s boat carried “twelve tons” of ginseng—a staggering amount, enough to fill 3,000 barrels and outweighing all the wild ginseng collected by 8,977 diggers in the entire state of Kentucky in 2003. As folklorist Warren Roberts has pointed out, Boone was more likely transporting twelve tuns—an old name for a barrel.

But whatever the size of Boone’s cargo, it’s indisputable that large amounts of wild ginseng were shipped from North America. It was the continent’s first export to Asia, and after the independence of the United States, a mainstay of the new nation’s economy. In 1784 a ship called the Empress of China set sail for Canton, completely loaded with ginseng root. John Jacob Astor, the fur and land magnate, got his start in business in 1786 by buying every scrap of ginseng root he could find and chartering a ship to take it to China. From this venture he received $55,000 in silver coin—equivalent to $1,140,000 in our day, and the stake that founded a trading empire that stretched from New York to Oregon.

Ginseng expert Scott Persons believes that the plant’s key role in America’s westward expansion has yet to be appreciated. “As people began to settle the land,” he says, “from the Eastern Seaboard all the way out west, to Minnesota and Missouri and Iowa, in many areas ginseng was a very important part of that, because it provided immediate cash income to the settlers until they could get a crop going. They sold it in order to buy the shovel, to buy the flour.”

In the Big Woods region of Minnesota, Persons tells me, there was a punishing economic depression in the 1860s. Crops couldn’t be sold, and settlers were desperate for income. Just as the homesteaders were beginning to give up and move to Iowa in search of better times, a group of ginseng buyers from Virginia arrived. “People were going across the woodlands almost at arm’s length digging ginseng. And it saved that section of Minnesota.” For three years, out of the 350,000 pounds of American ginseng exported to China annually, about 250,000 came from Minnesota. “They had ginseng festivals, ginseng balls, somebody wrote a ginseng polka and they danced it. It was like the rain came after a drought. It saved these people.” It also led to some of the earliest ginseng-related laws, when the Minnesota legislature passed measures to control the digging, but these proved to be too late. Within four years, the green gold rush was over, moved to other locations where the plant was still plentiful.

In his 1908 treatise Ginseng and Other Medicinal Plants, A. R. Harding of Ohio records the desperate poverty that drove some of the early diggers. He recalls, a number of years earlier, his having seen “one party of campers where the women . . . had simply cut holes through calico for dresses, slipping same over the head and tied around the waist—not a needle or stitch of thread had been used in making those garments.” While some diggers traveled on horseback, “Others travel by foot carrying a bag to put ginseng in over one shoulder and over the other a bag in which they have a piece of bacon and a few pounds of flour.”

Throughout the nineteenth century, American ginseng remained a lucrative business. In 1841, clipper ships carried over 640,000 pounds of dry ginseng to Asia. It is estimated that more than 60 million pounds of fresh ginseng roots were dug between 1783 and 1900. But ginseng was gradually becoming harder to find. As America’s population grew and white settlers pushed westward, more and more forest was cleared for farming, and more and more hunters were out digging the roots, from Maine to the Mississippi and beyond. By the late 1800s, it was widely acknowledged that wild ginseng was on the verge of disappearing. “It is becoming very scarce, and, unless a method of cultivation becomes practical, bids fair to be exterminated,” stated the 1909 edition of King’s American Dispensatory, a pharmacy reference manual.

And so it was that a scattering of growers began trying to tame “nature’s wildest child,” attempting to persuade it to grow in neat rows under wooden screens. Penn Kirk, of Arrowsmith, Illinois, was hardly the first, or the most successful, but he was probably the most entertaining.

The back cover of every issue of the Ginseng Journal features a blurry photograph of “The KIRK Ginseng gardens at Arrowsmith, Illinois”—but what is clear is that it’s an enormous spread. Wooden poles and lath screens stretch off into the distance, and underneath them rows of plants flourish on curved, raised beds. “Ginseng raising is like the raising of any other crop,” Kirk proclaims. “It is the most economical of all crops, taking so little room and work. A well tended town lot of it would buy a farm. I sold $526.00 worth of it from a little space of 30x105 feet last year. Had it been left in the ground one year longer it would have doubled in weight. We learn by experience. . . . One man received $204.00 for one crop on a space sixteen feet square. He tended it well. It could have grown in the shade on the north side of his house. One acre thus tended would have yielded $33,000. See?”

We learn in the third issue that the Ginseng Journal’s endless pages of get-rich-quick ads (“Mink raising...