eBook - ePub

Local Environmental Movements

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Local Environmental Movements

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Perspectives on Local

Environmental Movements

Chapter 1

Local Environmental Movements

An Innovative Paradigm to Reclaim the Environment

The environment is under siege nearly everywhere. Residential, commercial, and industrial development threatens national parks, streams, wildlife habitats, tidal flats and coral reefs, urban landscapes, and farmland in both Japan and the United States. No single private or public entity can counter this trend; the answer lies in a creative partnership involving local people, citizens’ groups, and governments at all levels. Strengthening local environmental groups and local governments can help protect and preserve the environment as a whole.

There are many local movements organized to pursue through collective action a variety of goals. The focus of this volume, however, is on those movements in Japan and the United States organized in response to environmental problems. These local environmental movements have geographic attributes. They originate in particular places. Their planning processes and subsequent campaigns occur in specific locales. The very existence of a local organization is rooted in notions of space and place—particularly of place. People develop strong emotional attachments to their local environments (Tuan 1974; Buttimer and Seamon 1980). Their sense of place is often especially acute when beloved environments—rivers, tidal flats, traditional urban landscapes, natural landscapes, or farmlands—are threatened or under attack. The chapters in this volume argue that local activism (1) creates a new focus on environmental concerns and ecosystem protection, (2) integrates a complex set of local issues that contextualize local movements, making it easier for such movements to coalesce with and strengthen national and regional environmental organizations, and (3) starts a process of local mobilization that propels future activism and appears to be effective in redirecting development policies toward both protecting the environment and enhancing social opportunities.

Local communities in Japan and the United States are facing a number of similar environmental issues, including the loss of farmland, the disposal of chemical waste, the problems associated with the use of nuclear power, and the preservation of historical-cultural landscapes and wildlife habitats. All these issues are being tackled by local groups, as evidenced, for example, by myriad local newspaper reports and, more specifically, a recent guidebook of citizens’ movements in Japan’s Miyagi Prefecture that includes contact details for seventy-five environmental groups (Sendado Kurabu 1991). The environmental movements discussed in this volume represent very diverse networks of people. Some of them are relatively loosely organized and some very highly organized. Most of them promote a holistic view emphasizing the preservation of nature and the restraint of unsustainable development. Many had their origins in the 1970s and 1980s.

Environmental issues are no longer the preserve of a few visionaries or intellectuals, having begun to engage the consciousness of the millions in the United States and Japan who fear the excessive cost of uncontrolled development, which non-Western countries other than Japan began to see in the 1980s as whole ecosystems came under threat. Transnational companies, forbidden from polluting their own backyards, used developing countries as dumping grounds for their industries’ most poisonous by-products and rode roughshod over attempts to regulate their destructive practices. As a result, local environmental movements in Asia and Africa have allied themselves with anti-imperialist movements.

Grassroots movements with local priorities should be distinguished from such worldwide movements with global priorities as the Green Movement. Local, grassroots movements engage thousands of people by offering them the opportunity to participate, whether in consensus decisionmaking, media events, focus groups, or nonviolent protests. The issues raised by the grassroots movements are, and will remain, of genuine concern for local communities. For example, when it turned out that neither market forces nor government bureaucracies were willing or able to step up and do anything about environmental degradation—first noticed in the early 1970s and the result of the postwar boom in both the United States and Japan—citizens’ groups in both countries emerged to take up the fight. In general, such groups have shown that the problem of environmental degradation can be tackled in the same manner as the problems of sustainable development and human rights.

Despite the fact that, in this first decade of the twenty-first century, national and international groups have dominated the headlines, local environmental movements are among the most vibrant, diverse, and powerful social movements on the planet. Their global distribution allows us a window on the multitude of ways in which different cultures mobilize. This volume is based on the premise that there is no one, single environmental movement and that the differences between the many environmental movements far outweigh their similarities.

In contrast to large nonprofit organizations, which represent national constituencies, grassroots support and advocacy groups represent local constituencies. And the accountability relations within these grassroots organizations flow from the bottom up rather than from the top down. The balance of power between the leadership and the rank and file often ebbs and flows over time, the two not necessarily seeing eye to eye at all times. Still, in order to maintain its control, the leadership must make sure that, by and large, it represents group members’ wishes.

There are, of course, top-down influences on local movements as well. Often, such movements address problems that are global in scope and attempt to implement solutions that were first proposed in the international activist arena. And they are also affected by their own national political and economic cultures. The United States in particular has proved to be fertile ground for environmental protest, particularly with regard to uncontrolled development. But this should come as no surprise to anyone since the time of Alexis de Tocqueville, the French political thinker and historian who more than two hundred years ago interpreted protest movements as the products of the politics of hope. That is, there must be, as there is in the United States, the assumption in place that certain rights do, in fact, exist before people will protest attempts to curtail those rights (Pakulski 1991, xxi).

Social movements, by their very definition, are amorphous political forms, living entities often undergoing rapid change and, therefore, often unable to be characterized by the methods of traditional institutional history. Social movements focusing on the environment are especially difficult to characterize because they so often function extra-institutionally, beyond the realm of government and nongovernment organizations, churches, and corporations. It is this latter factor that makes researching environmental social movements fascinating. What is revealed is politics in the raw, the nature of power relations and decisionmaking processes at the beginnings of issue cycles, before formalization. It was within environmental movements that a modern environmental sensibility was born in the 1960s in both Japan and the United States.

Studying local networks, informal groups, and developing movements demands somewhat different methodological techniques than does studying established institutions and corporate bodies. That is, while both primary and secondary sources on grassroots activism have been compiled and collected, much of the relevant research material has not, necessitating more than the usual amount of ethnographic fieldwork and ferreting out of supporting documentation. All the case studies in this collection are, thus, premised on the need to find better ways to engage the reality of environmental politics and, thus, it is hoped, better ways to resolve, even if only partially, environmental issues/problems.

While discussing specific movements, the essays deal with four key features identified by Offe (1985): (1) the actors in those movements (e.g., farmers, fishermen, women, the general public); (2) the goals of the movements (e.g., the protection of environmental interests); (3) the values of the movements (e.g., an ecological view of place); and (4) the mode of action undertaken (e.g., the advocation of local self-determination). Often, the movements are in conflict with technocrats, private entrepreneurs, and governments. Most of the essays reveal that integrating multiple objectives without losing track of the initial ground-level protests is vital to a movement’s success.

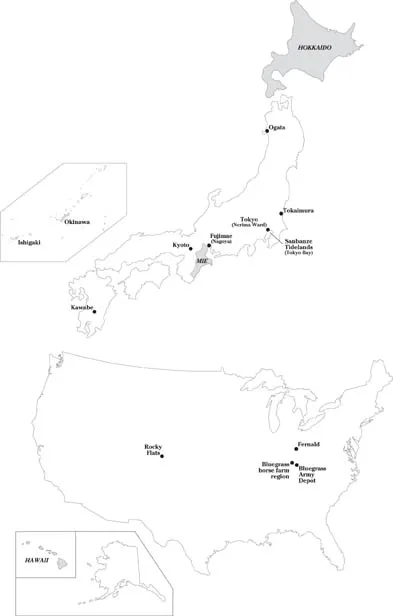

The movements discussed in this volume (see figure 1.1) fall into four categories: those protesting the effects of nuclear radiation and chemical weapons; those seeking to preserve rural and urban landscapes; those seeking to preserve the natural environment; and those protesting the effect of military activity. The strength and popularity of these movements can be attributed to their long history, objectives, committed leaders, and stature at the local and regional levels. It is especially to their credit that, in the face of the serious challenges presented by the popularity of the backers of development among the media and international agencies, they have kept concern for the environment and awareness of environmental issues alive at the grassroots level.

Perspectives on Local Environmental Movements

As background and context for case studies of local environmental movements in Japan and the United States, Richard Forrest, Miranda Schreurs, and Rachel Penrod, the authors of chapter 2, analyze the context and history of local environmental movements in the two countries, contrasting the movements themselves as well as the cultural, religious, political, legislative, and technological influences that have made environmentalism distinctive in both countries. The environmental movement in Japan is in some ways different from those in the United States and other Western nations. Japanese movements are victim oriented, concerned more with the negative impact on people than with the impact on the natural environment (McKean 1981). The goals of the movement are, therefore, very focused, the solution of specific local problems. American environmentalism is, by contrast, more broadly concerned with the preservation of the environment in its natural state, even when specific local issues are involved. Japanese environmental groups use a variety of methods—for example, direct action, petitioning, and filing lawsuits—in their effort to save the local environment. Unlike American groups, these groups are not hierarchically structured, which makes them more difficult to integrate into existing power structures. As a result, the Japanese environmental movement is far less unified than is that of the United States. Yet some Japanese movements have had a striking and unique impact on policymaking in Japan.

Figure 1.1. Location of case studies in Japan and the United States.

The last quarter of the twentieth century was a time of fertile intellectual activity, and many of the leading environmental thinkers developed ideas and skills during this period that shaped the modern environmental movement. The National Geographic Society is one example. It developed a powerful theory—fully articulated in many articles in National Geographic, the society’s monthly magazine—that humans and nature are interdependent but that humans have the power to cause irreversible damage to nature. The images of landscape published in the magazine helped make millions of people aware of the need for environmental protection. National Geographic photographs played a powerful role in the modern environmental movement by introducing readers worldwide to the beauty of nature and, subsequently, the need to preserve it. The photographs became concrete manifestations of the objects of environmental protection. In chapter 3, Stanley D. Brunn analyzes the role of the National Geographic Society in promoting environmental awareness among the readers of National Geographic.

By the beginning of the 1990s, environmental NGOs had become increasingly important actors in national and global environmental politics. They began routinely attending and influencing conferences dealing with environmental issues. They have found points of leverage that they can often bring to bear to help resolve problems. Flexible groupings of NGOs, local, national, and international, have proved crucial for progress. The complementary roles played by different types of NGOs can add more to an environmental movement than mere members of participating groups. In chapter 4, Kim Reimann explores the emergence and growth of local environmental movements in Japan and the connection between local and global social movements, showing how grassroots activists and NGOs in Japan were influenced by global trends and seized new international support to advance their cause.

The Case Studies

Protesting the Effects of Nuclear Radiation and Chemical Weapons

Nuclear power plants and their reactors dot the American and Japanese landscapes. In the United States, there are also several chemical weapons storage facilities. In fact, the United States and Japan are the first- and third-ranked countries in the world in terms of number of nuclear reactors (including those producing weapons in the United States). There were 118 reactors in the United States in 2000 and 55 in Japan in 2006. The 55 reactors in Japan—which generate a little more than 30 percent of that country’s electricity—are located in an area the size of California, many within 150 kilometers of each other, and almost all built along the coast (where seawater is available to cool them). Many of the reactors in Japan and a few of those in the United States have been sited on active seismic faults. Those so situated in Japan are located in the subduction zone along the coast, where major earthquakes (magnitude 7 or greater on the Richter scale) occur frequently. There is almost no geologic setting in the world more dangerous for nuclear power than Japan.

The performance of Japan’s nuclear power plants has been exemplary during earthquakes; either they have sailed through unruffled, or reactors have shut down automatically. Nonetheless, human error and cover-ups have generated unease. Japan’s Monju reactor, located in Tsuruga, Fukui Prefecture, has been shut down since it caught fire following a sodium coolant leak on December 8, 1995. An accident on September 30, 1999, at a nuclear processing plant in Tokai Village, Ibaraki Prefecture—caused by employee carelessness—killed two workers and exposed more than 660 nearby residents to radiation. In 2002, details of falsified inspection and repair reports forced the temporary closure of seventeen plants. And, in 2004, steam from a broken pipe that had not been inspected for two decades killed five workers in western Japan. In April 2006, the governor of Aomori Prefecture approved the location of Japan’s first commercial nuclear fuel reprocessing plant in the prefecture. In the town of Rokkasho at the northeastern tip of Honshu Island, Japan is working to get around the limits of the uranium supply. Inside a new $20 billion complex, workers service cylindrical centrifuges for enriching uranium and a pool partly filled with rods of spent fuel. Spent fuel is rich in plutonium and leftover uranium—valuable nuclear material that the plant is designed to salvage and reprocess into a mixture of enriched uranium and plutonium that can be burned in some modern reactors and could stretch Japan’s fuel supply for decades or more. Due to start in 2007, the Rokkasho complex includes housing for the inspectors from international agencies whose job it is to ensure that the plant is put to entirely peaceful purposes. Such a safeguard does not satisfy the opponents of nuclear energy. Deep suspicion of nuclear energy and its regulation remains in the country. Local opposition has, since 2003, forced three ut...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations and Tables

- Preface

- Part I: Perspectives on Local Environmental Movements

- Part II: Protesting the Effects of Nuclear Radiation and Chemical Weapons

- Part III: Seeking to Preserve Rural and Urban Landscapes

- Part IV: Seeking to Preserve the Natural Environment

- Part V: Protesting the Effect of Military Activity

- List of Contributors

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Local Environmental Movements by Pradyumna P. Karan, Unryu Suganuma, Pradyumna P. Karan,Unryu Suganuma in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Environmental Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.