![]()

1

Early Struggles and Foundations for Success

1875–1910

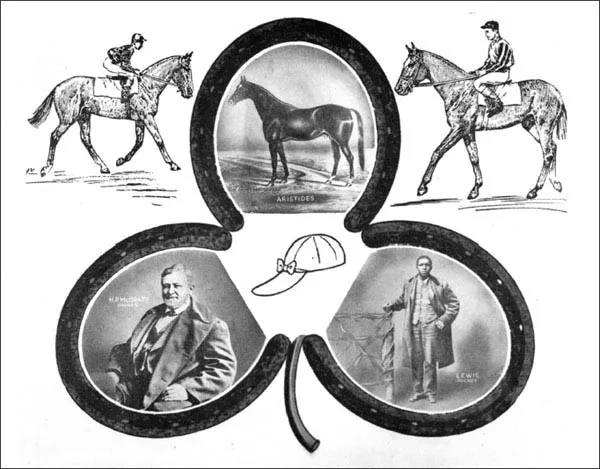

“Today will be historic in Kentucky annals as the first ‘Derby Day’ of what promises to be a long series of annual turf festivities of which we confidently expect our grandchildren, a hundred years hence, to celebrate in glorious rejoicings,” the Louisville Courier-Journal boldly predicted on May 17, 1875.1 That afternoon ten thousand curious and enthusiastic spectators filled the brand-new Louisville Jockey Club and Driving Park and witnessed history under a cloudless sky. Fashionable ladies and gentlemen from all parts of America were seated in the grandstand, and the clubhouse veranda was dotted with parasols, rocking chairs, and black waiters in white coats carrying trays of frosted silver cups. Wagons and carriages of all descriptions filled with locals from all walks of life were scattered across the infield. All had come to see the first running of the Kentucky Derby. The second of four races that afternoon, the inaugural Derby did not disappoint. Entered as a “rabbit” to set a fast pace for his favored stable mate, come-from-behind specialist Chesapeake, Aristides was sent to the lead early as planned by jockey Oliver Lewis, but saved enough energy to survive a late challenge from Volcano, thus achieving a surprising two-length victory. The crowd erupted in applause for the little red colt and his game jockey, who wore the orange and green silks of winning owner H. P. McGrath as horse and rider made their way to the winner’s circle—champions of the first Kentucky Derby.

Aristides, winner of the first Kentucky Derby, ridden by jockey Oliver Lewis, and owned by H. P. McGrath. (Keeneland Library, Lexington, Kentucky.)

Horse racing had been popular in Louisville since the late 1700s, but the city had been without organized Thoroughbred racing since the Woodlawn race course had closed five years earlier, a testament to the fact that while commercial breeding was already an established part of the state’s agricultural economy, Kentucky was by no means the undisputed capital of the American Thoroughbred industry that it would later become. In fact, in the mid-1870s, much of Kentucky’s identity to outsiders was based on its reputation as a hotbed of lawlessness and violence. Nine months before the first Kentucky Derby, the New York Times described the Commonwealth as “a land which produces more beautiful women, unrivaled horses, fine whisky, and blue grass than any other section of the universe.” But, the Times continued, “Some classes of its inhabitants . . . think it no harm to kill a man or two yearly to keep their senses of honor keen and their weapons bright.”2

For Meriwether Lewis Clark Jr., the first Derby marked the culmination of years of effort to create a world-class racecourse in Louisville. The series of events that led to the establishment of the Kentucky Derby was set in motion when the recently married twenty-six-year-old Clark (a grandson of famous American explorer William Clark and scion of one of Louisville’s oldest families) traveled with his wife to Great Britain and continental Europe in 1872, where he was introduced to many leading members of the English and French racing establishments. He toured their top racing facilities and was particularly impressed with English racing. Upon his return to Kentucky, Clark led an effort to build an upscale facility in the mold of Epsom Downs, one of England’s oldest and most famous racecourses, complete with a signature race modeled after the English Derby, a one-and-a-half-mile race for three-year-olds contested annually at Epsom. Clark convinced a group of 320 local sportsmen and business leaders to invest $100 apiece to fund the construction of a racetrack and grandstand for the Louisville Jockey Club and Driving Park Association, to be located on eighty acres of land owned by Clark’s uncles Henry and John Churchill (with whom Clark had lived for part of his childhood after the death of his mother). Within a decade the track would be known colloquially as Churchill Downs, destined to become the most famous racetrack in America.3

M. L. “Lutie” Clark, a dapper and physically imposing man with slicked-down hair and a flower habitually in his lapel, imagined the Kentucky Derby as an event on a grand scale from the beginning. He did not live to see the full fruition of his vision, but from the very first running the event received attention from national print media and racing fans across the country.4 Only twenty-nine years old when the track opened, Clark had already acquired cosmopolitan tastes for food and drink, and was known for hosting lavish parties in the clubhouse apartment that served as his residence during race meets. He hoped that the Louisville track would become a place for the city’s fashionable crowd to socialize, but he also offered free admission to the infield for all on Derby Day. Ladies were encouraged to attend the races but were segregated from the betting shed, which was considered an “inappropriate” environment for women. Clark wanted the track, the clubhouse, and the grounds to be well manicured and top class, even if that required expenditure of his personal wealth, which it often did. Clark’s Derby night parties at Louisville’s posh Pendennis Club were legendary: one year the dinner tables were arranged around an indoor pond filled with moss, ferns, a fountain, and live baby swans. Above all, Clark promoted the Kentucky Derby as a signature race and showcase for the racetrack.

Early journalistic prognostications for the Derby demonstrate that the race was special from its inception. To say that it reached lofty levels of popularity and cultural significance in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries from a starting point of complete national insignificance would be inaccurate, but the path toward the special place in American culture that the Derby eventually achieved was often bumpy and uneven. In an era when racing was conducted for the sake of sport as much as for profit, Churchill Downs struggled to survive financially in the early years, but the Derby was popular with race fans and high society, and its significance crossed state and regional boundaries. New York millionaire William B. Astor Jr. won the second Derby with a gelding named Vagrant he had purchased only weeks before. Among the ten rivals Vagrant defeated was Parole, owned by another New York millionaire, tobacco-manufacturing heir Pierre Lorillard IV (who would later become the first American owner to win the English Derby). In 1881 major New York owners Michael F. and Phillip J. Dwyer won the Derby with heavily favored Hindoo, one of the best horses of his era and part of the inaugural class of inductees at the National Racing Hall of Fame. The Dwyer brothers had been butchers in New York City before making a fortune in the meatpacking industry as suppliers of area restaurants and hotels. They would become major players in the eastern racing scene as racetrack operators and racehorse owners, though Mike Dwyer would also gain notoriety as one of the country’s heaviest and most reckless gamblers.

The following year the Dwyer brothers owned another of America’s top three-year-olds, Runnymede. Despite Lutie Clark’s efforts to recruit the colt to the Derby, the Dwyers were hesitant because they had been frustrated the previous year by their inability to find a bookmaker in Louisville to take their bets on Hindoo. The brothers told Clark that they would return to the Derby only if Clark would provide bookmakers to service their bets. When Clark told the Dwyers that none existed in the city, the parties reached a compromise: the Dwyers would be allowed to bring their own bookies. After securing their bets with the bookies at odds of 4-5, the Dwyers watched Runnymede find clear running room late in the race only to be caught deep in the stretch by a lightly regarded gelding named Apollo, who prevailed at the wire by a half length, becoming the first, and to date only, horse to win the Derby without making a start as a two-year-old. The Dwyers lost their bets with their bookies, but Louisville race fans gained a new and popular gambling option, and bookmakers would remain a fixture at the Derby for the next quarter century.

Another prominent American attracted early on to the Kentucky Derby was Berry Wall, a New York bon vivant, who was at least indirectly responsible for the creation of the important connection between the Derby and roses. Early in 1883 Wall was in Lexington, Kentucky, visiting a friend, when he met leading Thoroughbred owner and breeder Jack Chinn, who invited Wall to his farm thirty miles away in Harrodsburg the following day. At the farm, Wall was captivated by Chinn’s three-year-old colt Leonatus and asked to buy him. Chinn initially accepted, but quickly had second thoughts and cancelled the deal. Wall’s disappointment did not prevent him from betting on Leonatus to win the Derby with anyone who would take his money in New York in the weeks leading up to the race. Wall attended the Derby as a guest of Clark. After Leonatus easily bested his six rivals to win the ninth Derby, Wall refused to divulge the exact amount of his winnings but acknowledged, “I have a lot of money to spend.”5 He did just that by sponsoring a dinner at the Pendennis Club for thirty couples and a subsequent gathering later that night at the Galt House Hotel for sixty couples. The lavish decorations at the parties included American Beauty roses which, developed in France under a different name, had made their way to the United States only three years earlier. No one in Kentucky had seen this type of rose before and they earned rave reviews. Clark was particularly impressed and began presenting the Derby’s winning jockey with a bouquet of roses the following year, a tradition that would eventually evolve into the ceremonial blanket of roses worn by the winning horse today.

The Derby’s allure for the rich and fashionable, local and national, helped it to gain a reputation by 1886 as “undoubtedly the greatest annual event of the American turf,” according to the New York Times.6 On Derby Day that year the Courier-Journal evinced considerable enthusiasm: “The widespread interest in the meeting has attracted people from all over the country, and the city will be crowded today. That there will be a crowd at the races goes without saying. Everybody goes to the Derby; it is a Kentucky, almost a national, institution, and people who do not know one horse from another for the remainder of the year feel an intense interest in the colt of the year.”7 Anticipation was high, with record attendance expected.

The 1886 Derby proved to be a high point from which its national significance would fall for close to a quarter century. One of many threats to the Derby’s stature stemmed from hostilities between gold-rush millionaire James Ben Ali Haggin and Churchill Downs officials that year. Haggin was born in Harrodsburg, Kentucky, in 1822, the grandson of an early Kentucky settler. He practiced law in Shelbyville before heading west in 1849, where he made a fortune in mining. His sizeable land-holdings included part of the Anaconda copper mine in Montana, which he owned as a member of a partnership that included George Hearst, father of newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst. At one time, Haggin’s mine holdings were unsurpassed by any in the world. In 1880 he began a Thoroughbred operation in California that would soon become one of the largest and most successful in the country.

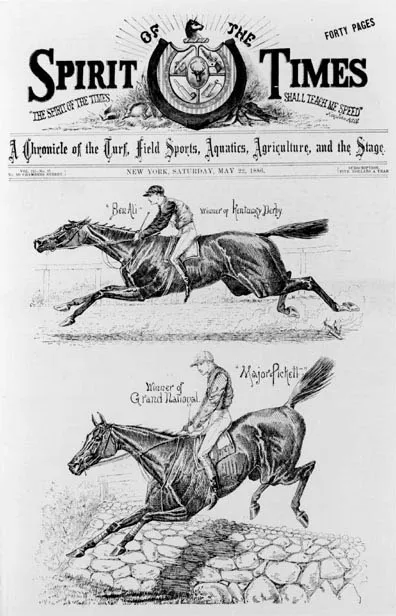

On Derby Day, 1886, Haggin became incensed at his inability to find a bookmaker to take a bet on his colt, Ben Ali, the favorite for that afternoon’s big race. Track officials had locked out the bookmakers over a contract dispute. After watching Ben Ali take the Derby by a half length, Haggin announced that if the bookmakers were not welcomed back to the track, he would leave Churchill Downs and never return. This was no small threat, as Haggin was ridiculously wealthy and one of the world’s leading owners of Thoroughbreds. The crisis seemed to have been averted when the bookies and track officials reached an agreement allowing for their return to business the following day. However, after harsh words were exchanged between the winning owner and a track official, Haggin left Louisville, vowing never to return to Churchill Downs and promising to see to it that his wealthy friends likewise boycotted the races.8 Haggin purchased Elmendorf Farm outside Lexington in 1897, which served as home base for his world-class breeding operation, but true to his threat, he would never again start a horse in the Derby.

Though the fracas between Haggin and Churchill officials certainly did not enhance the Derby’s reputation, the precise amount of damage it caused is difficult to measure, as major eastern owners were more concerned with the increasingly lucrative and prestigious racing scene in and around New York by that time anyway. Although major New York owners largely stayed away, the Derby nevertheless attracted horses from across the country for the remainder of the decade. In 1887 Elias Jackson “Lucky” Baldwin, founder of the original Santa Anita Park racetrack on his Southern California ranch and nicknamed for his uncanny success in various nineteenth-century mining ventures, sent his colt Pendennis from California to start in the Derby. Though the horse finished last, the presence of Pendennis at the Derby in 1887 shows that Haggin’s boycott of the Derby did not keep all the top national owners away from Louisville. In fact, the winners of the four Derbies immediately after Haggin’s departure were won by non-Kentuckians. In 1888 Macbeth II won the Derby for owner George V. Hankins, the “King of Chicago Gamblers.” The following year a colt named Spokane, bred and trained in Montana, narrowly nipped heavily favored Proctor Knott at the finish line and was declared the winner after a long deliberation by the placing judges (a decision that reportedly netted notorious outlaw Frank James a sizeable payoff on a bet placed on the winner). In 1890 “Big” Ed Corrigan, a Kansas City industrialist and Chicago racetrack operator, won the Derby with Riley, a horse he owned and trained.

Ben Ali, Spirit of the Times cover art, 1886. Ben Ali won the Derby in 1886, but his owner, James Ben Ali Haggin, had a greater long-term impact on the race. Following a dispute over access to bookmakers, Haggin told Churchill Downs brass that he would no longer race at the track and that he would see to it that his fellow top eastern owners did likewise. (Keeneland Library, Lexington, Kentucky.)

The appeal of the Kentucky Derby had never been based solely upon its significance in the world of horse racing; thus, the dearth of wealthy eastern owners would not necessarily have caused a noticeable downturn in the popularity of the race. But their absence, combined with the increasing popularity of new races for three-year-olds like Chicago’s American Derby and the proliferation of racing in and around New York City, indicated tough times ahead for the ...