![]()

1

INTRODUCTION—WHY WRITE A BOOK ABOUT SUNGLASSES?

Sunglasses are a small thing. They are an accessory, an add-on to life. Some people might question whether such an apparently insignificant thing is worth such study. But Lars Svendsen says that “an understanding of fashion is necessary in order to gain an adequate understanding of the modern world” (2006: 10), and I would like to say something similar about sunglasses in particular. Or, at least, that it might be worth knowing why, in the twentieth century, so many eyes—in images as well as in the “real” world—have been shaded. Sunglasses are usually small in size, but the market for them is massive. At the time of writing, 70 percent of Britons own sunglasses (Mintel 2012: online), in fact since the 1940s it has been claimed that “most people” own a pair (Corson 1967: 225). Most people probably also own umbrellas, but widespread ownership is not the only factor making sunglasses especially significant. The Luxottica group, who own Ray Ban and Oakley, are currently a mighty force in the fashion industry and, perhaps most importantly, sunglasses (and images of them) are everywhere in contemporary popular culture; in fashion, in film, in popular music, in advertising and marketing. Whether “subcultural”, “avant-garde”, or even aimed at children; the use of sunglasses, certainly in these images, goes way beyond any justification based on a need for protection against dangerous levels of light.

The reason for this is obvious, isn’t it? People want to look cool! But if this assumption is right, why do they want to be cool and what have sunglasses got to do with it?

This study was partly inspired by a very everyday incident, quite some time ago; on my way home after decorating what was to be my new flat, I stopped at a supermarket to get a pint of milk. I hurriedly got out of the car, grabbing my sunglasses. As I slipped them on, I wondered to myself why I had bothered—it wasn’t that sunny, and I really only had a few steps to go. I quickly realized that somehow the sunglasses had made me feel more presentable, and feel less embarrassed about my “scruffy” decorator’s appearance. As I approached the entrance, my reflection confirmed to me that, not only was I “more presentable;” to my amusement I actually looked “quite cool”... but of course whether or not I looked cool to anyone else is highly questionable, because cool is well known to be a slippery thing—subjective, elusive, and ever-changing. Whether I am cool (or ever was, with or without sunglasses) is irrelevant. This incident got me thinking about how often I had seen sunglasses used in popular culture in just this way, as a sign of some powerful, elusive, desirable quality.

Sunglasses in contemporary culture

As a lecturer in visual culture in a fashion department, I had observed that sunglasses have also been remarkably resilient to changes in fashion and indeed in the sartorial languages of cool. Since sunglasses became fashionable in the early twentieth century, they have remained a powerful component of the fashionable or cool image; in fact, it seems sunglasses are almost synonymous with fashion, underscored by the iconic images of fashion elite like Anna Wintour and Karl Lagerfeld, both recognizable by their tendency to wear shades indoors (film of Lagerfeld even shows him selecting fabrics and evaluating samples in them). Popular frame/lens combinations do get replaced by other styles; and occasionally they have been less ubiquitous, but even then, quite often, other intrusions on the eye (like fringes or hat brims) hold their place. Moments without any form of eye-shade in fashion certainly seem to be short-lived. Every level of the market, every season, every year, from subcultures and street fashion, to couture and luxury branding as well as now the focus of numerous blogs and online articles, sunglasses are an obvious sign of cool which seems to have incredible staying power.

Similarly in film sunglasses have become a cliché of film promotion, for example Lolita (1962), Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1998), The Matrix (1999), Leon (1994), The September Issue (2009) to name a paltry few. Reaching for an image to signify not just the fashion industry but also Hollywood, America, or indeed rock music, hip hop, pop culture, tourism, western culture more generally, sunglasses are a fall-back device in countless graphic designs. Why do sunglasses have such appeal across such wide cultural categories? Could there be something about the shared conditions of modern life that makes the appearance of shaded eyes generally—and desirably—meaningful? On T-shirts, necklaces, birthday cakes, children’s snacks, and Christmas cards, sunglasses have appeared as a key signifier guaranteeing desirability, an affirmation of desirable social distinction for a mass audience.

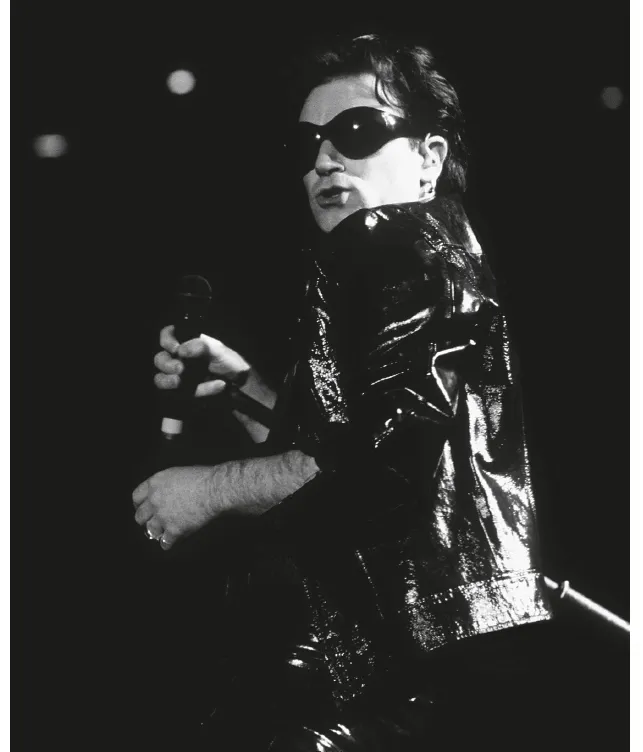

Evidently many notorious and beloved twentieth and twenty-first century figures have been known for wearing them, from Miles Davis to Lady Gaga. But the curious potency of sunglasses in contemporary social life can also be found in news stories about high-profile people who have been unexpectedly photographed wearing sunglasses. A snap of the teenage Prince William “cavorting in wraparound sunglasses” (Greenslade 1999) prompted a debate about “inappropriate” images and, indeed, about the entire role and position of the “modern royals.” Quite serious discussions about authenticity and identity were sparked off when the rock “legend” Bono suddenly—and uncharacteristically—began wearing very obvious sunglasses in the 1990s (Sawyer 1997), as they were when the Pope playfully donned the pair given to him by Bono while being filmed for the Jubilee 2000 campaign to write off Third World debt. This moment was allegedly “hastily cut” from the “live” TV coverage from the Vatican (Jelbert 2000). The list goes on but, in all these cases, wearing sunglasses was equated with displaying new or different values, controversial by virtue of their ability to make someone “good” look “bad.” On the cover of The Face magazine Bono was described as being “defrocked” when he took up the sunglasses, having previously been known for being “messianic,” earnest, and depicted as such.

Figure 1.1 Bono of veteran rock group U2, taking up sunglasses initially for his persona as “The Fly” on stage, 1993. (Photograph by Graham Wiltshire. © Getty Images.)

However, these journalistic discussions revealed that, maybe, it was good to look bad, and that this was a complex business. Were the sunglasses an ironic statement of “badness?” Or, did they (embarrassingly) represent “too much effort” to look cool? There was talk of loose morals, hedonism, insincerity, superficiality, but also of “inability to carry off” the cool demeanor. Even more complex was the idea that the sunglasses might reveal a more modest or self-conscious approach to “truth” appropriate to the postmodern world. For some the sunglasses said, “Yes, I know, all I am is a stupid rock star”, which somehow made Bono’s earnest persona more convincing. William’s wraparounds helped him “get down with the kids”; but also suggested a “louche, flash” lifestyle too close to fashion and celebrity to be suitable for a respectable future king. When Kanye West and Pdiddy offered Princes William and Harry a try of their “ghetto-fabulous” shades at the Concert for Diana several years after the furore over William’s wraparounds, they showed caution and “jokingly declined” (Daily Mail 2007), knowing the “bad visual copy” this could create. These complexities show there is something interesting here to study.

Figure 1.2 Princes William and Harry at the Concert for Diana in 2007 with Kanye West and Sean Coombs (aka Pdiddy). They “jokingly declined” West’s offer to try on some shades, but were happy to be snapped with what the Daily Mail called “rap royalty.” (© Tim Graham Picture Library, Getty Images.)

The book provides a brief history of the emergence of sunglasses specifically as a fashion accessory, but also of the development of their significance within popular culture more broadly, and, most importantly, a detailed investigation of the special relationship between sunglasses and that slippery concept of cool. Often regarded a bit suspiciously by serious fashion writers, cool is nevertheless in common use in popular fashion discourse, and some social theorists have claimed that cool is moving from its roots in black African American culture and the European aristocracy, to become the dominant ethic in western society, supplanting the Protestant work ethic (Pountain and Robins 2000; Poschart in Mentges 2000: 28). Theories of cool will be used along the way to question the meaning and appeal of sunglasses. But perhaps looking at the cultural expressions of cool which make use of sunglasses will also provide further insight into the more general question of what cool might be and why it seems to matter so much.

Existing studies

Some writing and research about sunglasses does already exist; to start with, extensive commentary in fashion blogs and by journalists testifies to their curious power. There are also some useful, heavily illustrated general histories of spectacles and eyeglasses which reference some sunglasses, offering dates and good visual information (although there tends to be a lack of distinction between sunglasses and spectacles). Sunglasses are sometimes treated as a fun but frivolous side-issue in these works; the major exceptions being Handley’s Cult Eyewear (2011), which details some sunglass-specific brands, and gives more attention to the cultural contexts in which certain brands and models developed their potential meanings; and Moss Lipow’s Eyewear (2011), which gives some historical context for the invention and development of sunglasses. How and why sunglasses were even invented is often unclear, partly because their current type-form emerged from a variety of reference points (corrective spectacles were in fact often tinted, used to disguise blind or disfigured eyes, and a plethora of goggles and other devices were in use before “sunglasses” became the dominant form). Being “mere accessories” with a technical element, sunglasses have often fallen through the gap between fashion and science; ignored by optical history as too frivolous, by fashion history as somehow not quite the main object of study.

Some short, mainly visual essays by Evans (1996) on sunglasses and Mazza (1996) aspects of the history and poetics relevant to sunglasses have set out brief—but telling—summaries of aspects of the history and poetics of sunglasses, looking at some of the cultural meanings and associations of different styles and forms and their status as “modern metaphors for sight” (Mazza 1996: 19). Sunglasses have also been studied in a number of psychological investigations (for example Edwards 1987; Terry 1989; Terry and Stockton 1993), many of which explore the impact of glasses on physical attractiveness as perceived by others, generally concluding that sunglasses make people more attractive, as opposed to a tendency for corrective glasses to make people seem more intelligent but less sexy (especially female wearers). Another theme emerging from these studies is the perception of authority and honesty, with corrective specs increasing it and sunglasses decreasing it.

None of these studies specifically address these contradictions or attempt to relate them to cool, although sunglasses do often get mentioned by those investigating cool (Pountain and Robins have called them “the sartorial emblem of cool”, for example, 2000: 9). Carter and Michael’s 2004 essay “Here Comes the Sun” usefully considers sunglasses specifically in terms of their “material-semiotic” relationship to the “cultural body”—identifying some complex potential meanings of the gaze mediated by shades. Influential twentieth century thinkers like Barthes, Goffman, Huxley, McLuhan, and Reyner Banham have also all paused to question the power of shades, but frustratingly none of them have really allowed sunglasses to be a focus.

Studying sunglasses

There are many ways to approach the study of sunglasses, and this book perhaps opens the field for scholars from a variety of disciplines. In this project, my goal was to investigate sunglasses as a signifier in popular culture. Although this project has a design-historical dimension, methodologically it sits within visual and material culture, inspired by the tradition of writers like Walter Benjamin, Siegfried Kracauer, and Georg Simmel, who analyzed the seemingly insignificant “fragments” of modern culture as a way of revealing a complex web of underlying cultural, economic, and ideological values. This tradition is echoed by recent developments in visual and material culture. Where meaning comes from, and how we interpret it, is not located in one place. It is more like a cloud of magnetic dust (which might look different from different angles). The meaning of sunglasses in an advertising or fashion image today is the culmination of decades of design development, technological change, use, representation, and the accumulation of myth in further representations and uses. This necessitates a multi-disciplinary and, in my opinion, a somewhat intuitive approach. This project is informed by some consideration of the material and social “realities” of sunglasses, but it is focused on what sunglasses allow people to dream of being, whether they wear them in real life or consume images of them. The focus of my research was therefore in the collection and analysis of pop cultural imagery featuring sunglasses (mainly from film, advertising, fashion), because these are reproductions of desire and aspiration targeted at the many. Documentary photographs and memoirs indicated how sunglasses were worn by potentially influential figures, and the British Optical Association’s archive of British and American journals of the optical industry from the 1890s to the 1960s provided evidence of how products developed and how they were marketed.

The choice of historical and theoretical material was determined by two major things—first the connection with cool suggested a number of starting points (e.g. jazz, other sub-cultures) and secondly, the generic types of sunglass designs and images which suggested certain contexts and connotations (e.g. aviators, novelty frames for beachwear). I looked at hundreds of images initially just seeking patterns and departures, considering the historical and discursive context for them. Themes emerged as starting points for historical or theoretical questions. For example, speed was an important theme both in terms of the “content” of sunglasses’ design (many obviously “aerodynamic” forms, e.g. the wraparound) and in the context of imagery featuring them (in cars, on motorcycles, etc.). Based on the assumption that sunglasses seem to signify cool, I investigated the relevant theory of speed for possible connections with cool and vision. The important thing was to create a conversation between the objects and images and the theory and history, enabling the objects and images to “speak”, revealing deeply felt concerns which may otherwise remain unconscious. Studying sunglasses tells us more than their own “biography;” here it reveals a novel way to think about coolness, which I hope will be useful to those interested in culture more generally.

The book begins with the cultural context for sunglasses’ eventual arrival in visual culture—modernity. Then it proceeds in thematic, roughly chronological chapters about key ideas for the meaning of sunglasses and their connection with cool: speed, technology, light, darkness, shade, and the eclipse. These categories link to a range of cultural and historical contexts in which sunglasses accrued (and continue to accrue) their meanings. The book concludes with a chapter summarizing the development of sunglasses’ relationship with cool and concluding on what this might reveal about cool more generally.

Finally, I must state clearly that I am not saying the meaning of sunglasses is fixed. That should be obvious. Neither does this book claim that sunglasses are always perceived as cool by everyone; not now, nor in the past. Indeed, as much popular commentary of sunglass-wearing shows, sunglasses are now a cliché of attempts to look cool—and since making any effort to look cool implies a distinct lack of cool, the person who wishes to look cool should proceed with caution where sunglasses are concerned, paying careful attention to the details of form and context ... Unless of course, they are using the signifiers of being “uncool” as a means to demonstrate their complete lack of concern for others and their rules about cool, which of course, has the potential to make them much cooler than the sort of person who might be afraid of making a sartorial mistake. Ironic and, perhaps, post-ironic forms of...