- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Reading Graphic Design in Cultural Context

About this book

Reading Graphic Design in Cultural Context explains key ways of understanding and interpreting the graphic designs we see all around us, in advertising, branding, packaging and fashion. It situates these designs in their cultural and social contexts.

Drawing examples from a range of design genres, leading design historians Grace Lees-Maffei and Nicolas P. Maffei explain theories of semiotics, postmodernism and globalisation, and consider issues and debates within visual communication theory such as legibility, the relationship of word and image, gender and identity, and the impact of digital forms on design. Their discussion takes in well-known brands like Alessi, Nike, Unilever and Tate, and everyday designed things including slogan t-shirts, car advertising, ebooks, corporate logos, posters and music packaging.

Drawing examples from a range of design genres, leading design historians Grace Lees-Maffei and Nicolas P. Maffei explain theories of semiotics, postmodernism and globalisation, and consider issues and debates within visual communication theory such as legibility, the relationship of word and image, gender and identity, and the impact of digital forms on design. Their discussion takes in well-known brands like Alessi, Nike, Unilever and Tate, and everyday designed things including slogan t-shirts, car advertising, ebooks, corporate logos, posters and music packaging.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART ONE

On message and off message

1

Branding as sign system: Semiotics in action

Grace Lees-Maffei

Semiotics, the analysis of signs, was an extremely influential method of understanding words and images developed in the twentieth century, from the publication in 1915 of Ferdinand de Saussure’s lectures on semiotic approaches to linguistics (Saussure 2013), to the early work of Roland Barthes in the middle of the century, such as his ‘An Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narrative’ of 1966 (Barthes 1977: 79–124). Structuralists sought to understand the underlying structures by which societies and cultures are organized. Structuralism and semiotics have been criticized for being too static, for taking insufficient account of the fact that societal structures and the meanings of signs are subject to constant change. Barthes’ thinking and writing shifted towards influential and dynamic post-structuralist understanding of meaning in culture in order to better recognize the constantly changing nature of cultural meanings. Post-structuralism as a name implies what comes after structuralism, as both a rejection of, and a continuation of structuralism. Semiotics continues to offer many useful techniques to graphic designers including the model of the sign, distinguishing connotation from denotation, and the mutually constitutive relationship between langue (a system of language) and parole (an individual utterance). Like the shift from modernism to postmodernism in design, examined in Chapter 5, the move from semiotics and structuralism to post-structuralism and deconstruction in cultural analysis is not only of historical interest, it informs the way design and culture are understood in our own century. This chapter introduces semiotics and structuralism, and the notion of branding as a sign system. It therefore paves the way for the following chapters 2 to 5, which take up the story of the move to post-structuralism through various case studies.

Introducing semiotics

In the modern period, which extends from the introduction of the printing press into Europe in the sixteenth century to the last days of the industrial period in the West, Western culture has prized originality of thought. At the same time, in the industrializing, industrialized and post-industrial phases of our societies, invention and innovation have been lauded, and in many cases rewarded. So, when two or more people make similar innovations, it is remarked upon as surprising, even though the very notion of originality is questionable and much innovation occurs collaboratively. Concorde, for example, was the product of collaboration between British and French engineers, while the paper clip, the light bulb, and even the Coca-Cola bottle (launched in 1915, the same year that Saussure’s Cours de linguistique générale – Course in General Linguistics – was first published) have contested origin stories (Lees-Maffei 2014). Semiotics, the study of signs (aka ‘semiology’), derives from linguistics and was developed by two original thinkers, Charles Sanders Peirce (United States, 1839–1914) and Ferdinand de Saussure (Swiss, 1857–1913). Saussure’s term ‘semiology’, and ‘semiotics’ which is used to refer to the Peircean tradition, are nowadays often bundled under the term ‘semiotics’ (Nöth 1990: 14).

Peirce was a polymath who made significant contributions to a number of fields including philosophy and mathematics as well as semiotics. Peirce’s theory of the sign, published in 1867, is complex, extensive and remains important in the field of linguistics (Pierce 1992). However, Saussure’s structural linguistics has exerted more influence in the study of cultural production and specifically design because his writings in French influenced the French structuralists, chiefly Roland Barthes, and the community of French theorists of literature and culture including such towering figures as Michel Foucault (1926–84). It is therefore understandable that in seeking to chart the development of Modern Criticism and Theory in his anthology of that name, a leading English Literature scholar, David Lodge, begins his chronological arrangement of texts with Saussure (although a subsequent edition put Marx before Saussure), while Peirce is represented not by his writings but rather by a couple of mentions in passing in the work of others (Lodge 1988; Lodge and Wood 2013).

Peirce proposed three categories of signs: iconic, indexical and symbolic. The iconic sign is a resemblance or representation, such as a drawing, a map, a photograph or a pictogram. Pictograms are the oldest form of writing, while contemporary examples are seen in road signs and other public places. Pictograms are distinct from the more abstract ideograms, which are indexical signs. The indexical sign has a physical connection to its referent (to which it refers), such as metonymy (the part representing the whole) as in the use of smoke to represent fire, and the pen to represent writing, learning and reason as in ‘The pen is mightier than the sword’. Ideograms are learnt signs; examples are found in Egyptian hieroglyphics and Chinese writing. Peirce’s symbolic sign stands for, or represents, something else and relies entirely on convention for its meaning. Examples include the Christian cross and the warning triangle traffic sign. Symbols entail suggestive and subjective interpretations: an image may mean different things to different people. Peirce’s sign categories overlap; an image may present a naturalistic figure with a secondary conceptual or symbolic meaning.

We can apply these ideas to the notional example of a greetings card designed to mark the birth of a baby. The card might feature a dummy, or pacifier, and two different cards might be available, one pink and one blue, based on a learnt, conventional association with girls and boys, respectively. The image of the dummy is iconic. It functions as a metonymical symbol of the baby who may suck the dummy. The baby is therefore indexically implied. The card’s symbolic message is one of welcoming a new baby and wishing her or his parents well.

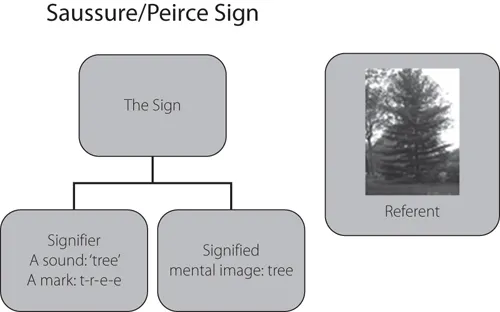

For Saussure, each instance of language, called parole, forms part of the langue, or system of language, and must be understood in that context. A sign is made up of a signifier (a word, whether written or spoken, or an image), a signified (the idea put into the mind of the receiver when contemplating the denotation) and a referent (the thing referred to). (Figure 1.1) Breaking the sign down into constituent parts in this way is useful for comprehending the difference between denotation (words or sounds in messages) and connotation (the meanings indicated by the messages). The relationship between a thing and its sign is learnt and arbitrary, not natural or innate. However, through familiarization and habit, signs can come to seem natural or inevitable. In English, trees are indicated by the letters t-r-e-e, forming the word ‘tree’, and by the sound ‘tree’. In France the same tree would be indicated by the name ‘arbre’ or the sound of that word. The fact that different languages have different words for the same things serves to highlight the arbitrary nature of the connection between word or image, sign and the thing it indicates.

Figure 1.1 Diagram of the Saussure / Peirce sign.

Saussure posited two ways of understanding language, the syntagmatic and the paradigmatic. In the former, combinatory relationships are explored, so that individual phonemes or sounds are seen to work in combination with others, as in ‘c-a-t’, for the word ‘cat’, and individual words combine with other for the meaning of phrases, as in ‘cat-sat-on-mat’ for the phrase ‘The cat sat on the mat’. Paradigmatic approaches emphasize difference; we understand words through their difference from others in the same language system. We understand ‘cat’ because it is not ‘sat’, ‘mat’ or ‘bat’. Saussure’s work has been criticized by some for its use of a synchronic approach, which takes a slice of time, the contemporary moment, and examines the evidence available in the present, rather than a diachronic approach which considers development over time. Synchronic models do not take account of the fact that language, culture and meaning change over time.

But what about signs, which resemble the thing, or concept, to which they refer? Onomatopoeia is the term for a word mimicking the sound of the thing it denotes, such as ‘sizzle’, ‘bang’, ‘miaow’ or ‘squeak’. Again, the existence of different onomatopoeic words in different languages points to their arbitrary nature. The dominance of English as a global language means that English onomatopoeic words are increasingly found in other languages. However, these loan words accompany indigenous onomatopoeic words which are often quite aurally distinct, such as the Turkish ‘hev hev’ or the Russian ‘gav gav’ (гав-гав) for ‘woof woof’. Saussure compares a ‘French dog’s ouaoua and a German dog’s wauwau’ to illustrate that ‘onomatopoeia is only the approximate imitation, already partly conventionalised, of certain sounds’ and that, furthermore, ‘onomatopoeic and exclamatory words are rather marginal phenomena, and their symbolic origin is to some extent disputable’ (Saussure in Lodge 1988: 13).

How does this apply to visual resemblance? Wouldn’t a drawing of a tree, for example, have a more natural or inevitable connection with the thing it represents, because it resembles a tree? Again semiotic distinctions are useful. A visual signifier, in the form of a drawing of a tree, might prompt the signified of a generic tree, and the category of vegetable matter that we group together as trees. This would be the case however individuated the drawing of the tree might be, even if it was drawn from life or a photograph of a specific tree, unless the recipient knew the tree in question, in which case the signifier would communicate the signified of that specific tree. In certain contexts, a drawing of a tree might connote home, England (for an oak tree, perhaps), Canada for a maple tree, roots, family trees, mother, father, friend, nature, specific gardens or gardeners, and so on.

Peirce’s notion of indexical signs is useful here. An indexical sign indicates a thing (or idea) and the connection between the sign and the thing is learnt. For example, a sign showing smoke affords a learnt indexical connection with fire. Smoke is not fire, but as we know proverbially, there is no smoke without fire. Smoke is therefore a sign for fire. An exception would be the group of ‘No smoking’ signs which show smoke in order to debar its production via cigarettes.

Semiotics and structuralism

Saussure’s structuralist linguistics formed the basis of a structuralist approach to understanding society and culture. Structuralists have sought to explain the underlying structures by which diverse societies have been organized, and the myths devised to understand and explain those structures. A key exponent was the anthropologist/ethnologist Claude Levi-Strauss (Belgian, 1908-2009). In works such as the first volume of his Mythologiques, called The Raw and the Cooked, which appeared in French in 1964 and in an English translation in 1969, Levi-Strauss examined 187 indigenous American myths, noting convergence around repeated binary oppositions such as raw and co...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title

- Title

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Reading graphic design in the expanded field: An introduction

- PART ONE On message and off message

- PART TWO On legibility and ambiguity

- PART THREE On paper and on screen

- Index

- Plates

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Reading Graphic Design in Cultural Context by Grace Lees-Maffei,Nicolas P. Maffei in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Design & Design General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.