![]()

PART ONE

Discourses

![]()

1

The retro problem:

Modernism and postmodernism in the USSR

Richard Anderson

From its first emergence in Soviet architectural discourse, ‘postmodernism’ was a highly contested term. It was unclear whether postmodernism referred to a broad reorganization of professional conventions that could adequately describe parallel developments in the capitalist and socialist worlds, or whether postmodernism was merely an expression of late capitalist ideology – and therefore foreign to Soviet theory. The early Soviet debates on this concept, which unfolded from the late 1970s roughly to the announcement of Mikhail Gorbachev’s program of Perestroika in 1985, betray a tension between a clear enthusiasm for the theories and projects emerging in Western Europe and North America and an awareness of the specificity of Soviet architectural culture and production. Occurring in the decades Leonid Brezhnev called ‘developed socialism’, the debates on postmodernism register the theoretical and practical development of the Soviet profession in an era commonly described as one of ‘stagnation’, for postmodernism served as a catalyst for Soviet architects to conceptualize an enriched, humanized, and communicative architecture appropriate to the growing needs of a mature socialist society. Yet some critics suspected that the alleged permissiveness and dependence on historical forms characteristic of Western postmodernism might correspond to a desire among an older generation of Soviet architects to return to the formal ‘excess’ of the Stalin era. Postmodernism would thus become entangled with the so-called retro problem that confronted Soviet architects. Ultimately, the debates that enveloped postmodernism precipitated a theory of Soviet architecture’s historical development that not only questioned the validity of the term as a description for Soviet production, but also cast doubt on the applicability of ‘modernism’ as such to the Soviet context.

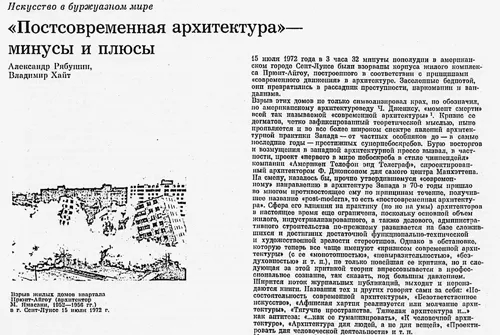

The first sustained discussion of postmodernism in architecture appeared in Soviet discourse in 1979. In October of that year, the journal Dekorativnoe iskusstvo SSSR (Decorative Art of the USSR) published an essay entitled ‘Post-Contemporary Architecture – Minuses and Pluses’ co-authored by Aleksandr Riabushin and Vladimir Khait (Figure 1.1).1 The very title of the essay – ‘post-contemporary’ (postsovremennaia) as opposed to ‘postmodern’ (postmodernistskaia) – registered the novelty of the concept of postmodernism in Russophone discourse. It also highlighted the fact that Soviet architects consciously avoided the term ‘modern’ when discussing architecture of the Soviet period. The latter was typically described as ‘contemporary’ (sovremennaia) architecture. Both the venue of publication and the status of the authors lent authoritative weight to the essay. Dekorativnoe iskusstvo SSSR was a widely read journal published by the Union of Artists of the USSR. Khait was a well-known architect and critic who had written extensively about the architecture of Brazil while also serving as a director of the Department of Contemporary Foreign Architecture at the Institute for the History and Theory of Architecture.2 Riabushin commanded even greater authority. A doctor of architecture, Riabushin had risen to the heights of professional leadership in the 1970s. In 1975 he was elected to the executive committee of the Union of Soviet Architects, for which he served as chairman of the ‘Theoretical Club’. In 1981, he would become a secretary of the Union’s executive committee, ensuring that his ideas would shape official architectural discourse in the USSR.3

FIGURE 1.1 Aleksandr Riabushin and Vladimir Khait, ‘Post-Contemporary Architecture – Minuses and Pluses’. Source: Dekorativnoe Iskusstvo SSSR, October 1979 [Courtesy of Richard Anderson].

Riabushin and Khait began their essay of 1979 with a description of a well-known moment in the genealogy of postmodern architecture: ‘On July 5, 1972 at 3:32 pm in the American city of St. Louis the slab blocks of the Pruitt-Igoe housing estate, which were constructed in accordance with the “modern movement”, were blown up.’4 This appeal to the famous opening statement of Charles Jencks’s The Language of Post-Modern Architecture – which would itself be published in Russian translation in 1985 – served as a preface to a wide-ranging discussion of recent trends in the architectural production of the capitalist world. Following the American critic Paul Goldberger, Riabushin and Khait described the absence of utopian ambitions as a characteristic feature of postmodern architecture.5 Among the other elements of the new trend, they noted a desire for a rich formal language, in opposition to the alleged symbolic poverty of what they vaguely referred to as ‘functionalism’; a typical orientation towards ‘upper-middleclass’ consumers; and an interest in historical citation. Riabushin and Khait wrote that although postmodernism was ‘to a certain extent a foreign phenomenon’, they maintained that it was the task of Soviet architectural criticism to observe ‘strict objectivity’ in criticizing both the architecture of the modern movement and the emergence of postmodernism. In their analysis, the latter represented a ‘capitulation’ of the utopian aspirations of the ‘pioneers’ of the modern movement and a turn towards ‘submissive service to the client’.6

Such an assessment of the role of postmodern architecture in the West did not, however, mean that this work was not of fundamental interest to Soviet architects.7 On the contrary, Riabushin and Khait insisted that it was vitally important for Soviet architects to understand recent developments in the West, suggesting that they might have an impact on Soviet practice as well. To establish this point, while simultaneously enforcing the ideological gap separating Soviet architecture from that of the capitalist world, Riabushin and Khait were driven to difficult, but rhetorically necessary circumlocutions. Their most important statement of the value of postmodernism for Soviet practice was the following:

Of course, a significant part of the professional methods in the work of creative artists of the West prove to be linked with bourgeois ideology – owing to their existence [bytovanie] in the system of bourgeois society. [But] experience shows that in a different environment such techniques may be determined by fundamentally different ideological content. That is why it is important to clearly define their ideological content – to ‘cleanse’ [ochistit’] the new professional methods of work developing in architecture and building today.8

With this, Riabushin and Khait suggested that Soviet architects might assimilate practices derived from the work of architects in the capitalist world. These practices needed only to be ‘cleansed’ of their ideological content.

But as postmodernism emerged in Soviet architectural discourse in the late 1970s and early 1980s, it did so against the background of fundamental transformations in the aims and ambitions of Soviet architectural practice. The interest that Riabushin and Khait expressed in the ‘professional methods’ associated with postmodernism corresponded to a widespread interest among Soviet architects and critics in the ‘humanization’ of architecture. By the late 1970s, objections to the dominance of the material and technical qualities of architectural production had become a commonplace in Soviet architectural discussions. The emphasis on production had, many claimed, led to the impoverishment of the ‘emotional’ aspects of architectural design. Regional architectural forms from the Soviet Union’s republics often served as sources for emotionally communicative properties.9 The critic and historian Iulia Kosenkova, for example, described the assimilation of national forms as a method for the emotional enrichment of Soviet architecture. Writing in 1978 on the architecture of Tashkent, Kosenkova noted that ‘the birth of an emotional architecture that is directed at the human senses is one of the most characteristic features of today’.10

When Riabushin and Khait wrote of the need to ‘cleanse’ foreign methods for potential use by Soviet architects, they did so in full awareness of the widespread desire for a reorientation of Soviet practice towards national and communicative forms. In 1982, Riabushin, now serving as secretary of the executive committee of the Union of Soviet Architects, reiterated these themes at a conference on architecture and ideology held in Kiev. He urged his colleagues to ‘critically evaluate the state and new tendencies in our creative practice, giving attention to the real expectations of Soviet people, their desire for a varied, rich architecture that is nationally and historically inflected’.11 More importantly, he stated that Soviet architects ‘must evaluate the dogma of functionalism, our preoccupation with technological aspects of architecture, and the tendency of modernism in architecture’.12 This was a double imperative: to re-evaluate Soviet architecture’s relationship to modernism in an effort to achieve an architecture rich in historical and national inflections. Such statements indicate that whatever impact postmodern theory had on Soviet architecture, it did not initiate the reorientation of Soviet practice in the 1970s and 1980s; rather, it served as a catalyst for processes already underway.

The parallels between the USSR and the advanced capitalist world that became apparent at the turn of the decade provoked a range of reactions among Soviet critics. Some felt that postmodernism could aptly describe these shared interests. Others rejected the concept of postmodernism outright. The variable reception of American architecture by Soviet critics over the course of the 1970s provides evidence of these divergent views. This is particularly clear in the Soviet reception of Robert Venturi. As early as 1972, key portions of Venturi’s Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture had been translated into Russian and made widely available.13 The translation editor of Venturi’s text, Andrei Ikonnikov, offered a critique of this work, writing that ‘pessimism, born of social passivity, is the principal weakness of the theory and practice of Robert Venturi’.14 In 1979, the same year that Riabushin and Khait published their seminal essay on ‘post-contemporary’ architecture, Ikonnikov offered further condemnation of Venturi’s work in his book Arkhitektura SShA (Architecture of the USA).15 In this book, he interpreted Venturi’s position as a call for the architect to renounce an active position in society and avoid assigning professional architectural concerns to the user. The architect’s task, in Ikonnikov’s interpretation of Venturi’s theory, was to create a neutral structure – the decorated shed (zdanie...