![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Setting the Stage: The Glass Menagerie

The Glass Menagerie marked Tennessee Williams’ critical and popular breakthrough in his home country. After acclaimed productions in Chicago and New York in 1945, the play quickly proceeded to have an international impact. The memories of the narrator Tom who recalls the constant fights with his mother Amanda, an ageing Southern belle, and his struggles to shake off his guilty conscience for having abandoned his fragile sister Laura whose life revolved around her collection of glass animals, also appealed to theatre artists and audiences in Sweden and France. This chapter briefly traces the opening productions of The Glass Menagerie in Stockholm (8 February 1946) and in Paris (23 April 1947). While the play provoked neither sexual anxieties nor racial fantasies, it nevertheless proves important to understand initial processes of production, reception and cultural translation of Williams. Of particular relevance are the divergent values attached to stage realism as well as the critical interpretation of Laura’s femininity. Finally, the chapter also explains agent Lars Schmidt’s savvy business strategies to establish Williams’ name throughout Sweden within less than a year.

Stockholm 1946: European opening

Judging from the audience’s mixed reactions on opening night at the Royal Dramatic Theatre (Dramaten), Glasmenageriet provided little indication of Williams’ future popularity. The applause was sparse and the Dramaten’s experimental studio stage was far from sold out. A review in the morning paper Dagens Nyheter scolded the jaded attitude of the Stockholm audience, asking it not to be so ‘stingy with applause’ especially when offered a play of such a high quality (Gamson 1946). Critics were generally impressed by the play’s mixture of realistic aesthetics and symbolistic techniques and its fragile characters and poetic language, which is why some drew a comparison to Henrik Ibsen’s The Wild Duck (Barthel 1946; Siwertz 1946). Svenska Dagbladet, one of the country’s most respected newspapers, deemed Williams to be ‘the most promising among those American authors who seek to replace the conventionally realistic theatre with a freer and more imaginative dramatic poetry’ (Selander 1946).

While many reviewers welcomed the arrival of a new American playwright and were intrigued by Williams’ idea to let one of the characters’ memories propel the plot, their assessments of the merits of the actual mise en scène were mixed. Director Stig Torsslow respected Williams’ elaborate stage directions and infused his production with a dreamlike and non-realistic atmosphere, but also added several components that were deemed ‘unnecessarily harsh’ (Almqvist 1946). Transparent curtains and lighting effects helped establish the contrast between past and present. Whenever Tom stepped into the present, a spotlight was directly on him. In order to mark the passing of time between scenes, the stage was completely dark while a single violin played a sad tune and slowed down the rhythm of the production considerably. Dance music offstage suggested life beyond the claustrophobic surroundings of the shabby, depressing apartment which was framed by a dirty brick wall. Morgon-Tidningen wrote that the director could not decide between ‘unadulterated dream play with bold stylisation or realistic theatre’ (Beyer 1946), hence why the production ended up somewhere in-between.1

Torsslow conceptualized the main action of the play as filtered exclusively through Tom’s memories of his dysfunctional family, and he directed the actors accordingly. As a result, Mimi Pollak’s interpretation of Amanda did justice to Tom’s memories of a dominant and overbearing mother (Figure 1). Her telephone calls achieved the desired comical effect, but Torsslow also turned her into a ‘caricatural showpiece’ (Beyer 1946) that induced ‘Strindbergian shudders’ (Siwerts 1946) and was ‘as pleasurable for the nerves as a dental drill’ (Svensson 1946).2 For his part, Uno Henning seemed too old to play the part of Tom despite his undeniable talent. Having a 50-year-old sailor act as narrator addressing the audience directly caused no immediate problem, but whenever Tom stepped through the transparent curtains back into the past, the age difference between him and his sister Laura (played by 24-year-old Nancy Dalunde) became too strikingly apparent. Moreover, Expressen’s reviewer criticized him for speaking with ‘the voice of a communist-expressionist Berlin actor from the 1920s’. The same reviewer, however, was impressed by the long scene between Laura and Jim and exclaimed: ‘[T]his is what the art of theatre looks like’ (Harrie 1946).

FIGURE 1 Mimi Pollak in Glasmenageriet, Royal Dramatic Theatre (1946), and Jane Marken in La Ménagerie de verre, Théâtre du Vieux Colombier (1947). Photo: Sven Järlsås, © Kungliga Dramatiska Teatern; © Studio Lipnitzki/Roger-Viollet/The Image Works.

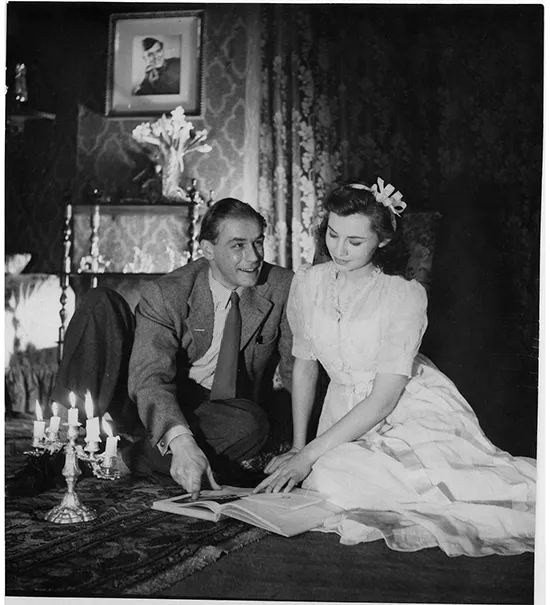

Laura and her presumed gentleman caller indeed became the focal points of the production (Figure 2). Dalunde’s genuine portrayal of Laura’s innocence and naïveté was deemed to be a highlight of the production by many reviewers, one of whom noted that ‘[s]he created something infinitely beautiful of this inhibited girl with her large anxiety, her ailing foot and her inferiority complex’ (Beyer 1946). Even more enthusiastic was Svenska Dagbladet: ‘One rarely gets to see the absolute, naive and touching virginity presented onstage in such a perfect way’ (Selander 1946).3 Olof Bergström also received positive reviews for his performance as Jim and was ‘magnificent in his self-confidence, splendid and irresistible – until he just as convincingly switched over to a decent and lumpy boyish despair’ (Harrie 1946) once he realized how much he had hurt Laura.

FIGURE 2 Olof Bergström and Nancy Dalunde in Glasmenageriet, Royal Dramatic Theatre (1946). Photo: Sven Järlsås, © Kungliga Dramatiska Teatern.

The majority of the leading theatre critics were middle-aged men, suggesting that by the time Williams arrived, they were already well established and respected as cultural arbiters. They largely came from a middle-class background and were equipped with a university education, sometimes with a major in literature studies or languages. Theatre reviews were a respected genre in their own right and reports from an opening night held significant news value. Importantly, critics were aware of their pedagogical assignment to introduce new playwrights and explain and contextualize new artistic currents or theatrical genres to their readers (Helander 2003: 178–87).

Ebbe Linde (1897–1991) serves as a recurring example of a critic who greatly facilitated the cultural translation of Williams in Sweden. Apart from having a background as a university professor in electrochemistry and working as a translator of classical and modern drama, Linde was also the author of satirical and erotic poetry. During Williams’ heydays, he was the main theatre critic for the literary journal Bonniers Litterära Magasin (1941–53) and Dagens Nyheter (1948–65), one of the largest and most influential morning papers in Sweden. Fascinated by psychoanalysis, internationally minded and with political attitudes shaped by anti-authoritarian convictions, his work was distinguished by ‘a resistance to the normative and fascination of the transgressive, be it sexuality or the literary canon’ (Granqvist und.). All of these characteristics explain why he always treated Williams and his plays with respect, even when he did not agree with certain artistic choices. When reviewing Glasmenageriet, he drew a comparison to Anton Chekhov and highlighted how a good drama should be reminiscent of a good short story, whose strengths and merits lie less in the actual plot and more in ‘the revelations about life it is capable of shedding over an environment and a group of characters’. He concluded: ‘Tennessee Williams really is a poet’ (Linde 1946; emphasis in original), a statement that would be echoed by many artists and critics in both Sweden and France over the following two decades.

The day after: Conquering the nation

Although hardly an undisputed success, the opening of Glasmenageriet at the Dramaten set an important precedent that spoke to Lars Schmidt’s talents as a negotiator, publisher and agent. A mere twenty-four hours after the Stockholm production, Gothenburg City Theatre presented its own interpretation of the play. This pattern of introducing the same play into the repertoire of multiple theatres during the same season or calendar year became a defining characteristic of Schmidt’s publishing tactics and promotional endeavours, all of which served to increase both the public’s interest in the stage work and his own financial profits. In Sweden, Williams was launched and marketed as a popular and commercial playwright who had mass appeal for the entire country well before his plays were turned into successful movies. In October 1946, both Helsingborg and Malmö City Theatre in the South of Sweden presented two further productions of Glasmenageriet. Meanwhile, the national touring company Riksteatern went on tour with the Dramaten production to offer audiences in more remote parts of the country the opportunity to see one of the most discussed plays of the year. Without engaging in a detailed study of each of these productions, suffice to say that directors were most inventive in their stage solutions for the various temporal threads of the play, playing with lights and curtains or letting Tom step forward onto an apron stage for his narrative monologues. The play itself was received in very favourable terms and critics consistently singled out the scene between Laura and Jim as a highlight (D. 1946; Lostell 1946; Perlström 1946; Söderhjelm 1946). GT called Williams a ‘poet’ and applauded him for striking the right balance between ‘bitterness’ and ‘tenderness’ (Thorén 1946); Social-Demokraten praised the play for being ‘melancholic and wonderfully charming’ (Tom 1946); and Ny Tid raved about Williams’ ability to show how life’s cruelties were destroying the frail and singled out the play as a representative example of the artistic values and innovative qualities provided by ‘the seemingly inexhaustible flow of new American drama’ (E.W. 1946).

An interesting document is a relatively short notice in Aftonbladet that reported on the progress of Riksteatern’s tour throughout the small towns. At first, audiences seemed intimidated by the visit of the reputable ensemble, but warmed up once they realized that the play on offer was quite entertaining. This, in turn, led to valuable word-of-mouth praise. One night, a firefighter who was assigned for security reasons volunteered to be scheduled for a second shift the following day, because he was so impressed by the play and wanted to see it again (‘Landsorten’ 1946). This seemingly unimportant anecdote reveals Williams’ popular appeal and, by extension, commercial viability that extended beyond the middle-class audiences at the Dramaten in Stockholm to broader segments of the population in every corner of the country.

The commercial instincts of Schmidt cannot be underestimated to explain how Williams, in the span of nine short months, was on his way to becoming the most popular international playwright of the post-war era in Sweden. Thanks to his shrewd acquisitions and innovative marketing as well as his good relationships with managing directors, Schmidt’s publishing house enjoyed a nearly complete monopoly of new American plays produced in the Nordic region within a decade after the company’s founding. A brief comparison with neighbouring Finland puts this into perspective and further highlights the unique position that Sweden held in introducing and spreading post-war American theatre. Not only did Finland have significantly different linguistic conditions due to the split between Finnish-speaking and Swedish-speaking Finns but the country also felt the devastating effects of the Second World War more acutely than Sweden did. In 1952, theatre scholar William Randel highlighted the popularity that American theatre enjoyed in Finland since the mid-1920s. Statistics showed that compared to the considerably larger number of Finnish-speaking theatres, the Swedish-speaking theatres of Helsinki (Swedish name: Helsingfors), Turku (Åbo) and Vaasa (Vasa) produced American plays much more frequently. Swedish translations were more readily available and language ties facilitated cultural exchanges with Swedish theatres or tours to the Scandinavian countries. Further elaborating on contextual aspects, Randel concluded his article with a harsh criticism of the post-war distribution of royalties, which he believed fostered the larger presence of American plays in Finland’s Swedish-speaking repertoire:

New York agents currently sell most acting rights to Swedish middlemen who add 2 or 3 percent in passing them on to Finland. Swedo-Finn producers may use translations already made for theaters in Sweden, but the Finnish Theatre Association must not only pay the extra royalty but have a Finnish translation made. This purely financial consideration may account for the greater number of American plays presented by Swedish-language theaters. (1952: 300)

While this criticism stands as another example of how economic conditions factored into the cultural translation of American plays into the Nordic market, Randel also tacitly underscored the business practices of Schmidt, who figured as the head of the operation of those ominous, unnamed ‘Swedish middlemen’. Step by step, Schmidt widened his sphere of influence and methodically increased his income by first conquering neighbouring Nordic countries and eventually, as we shall see in Chapter 3, continental Europe and France.

Paris 1947: A truly foreign import

The first time French audiences were exposed to Williams was not through a domestic production, but a guest stint in April 1947 by the Geneva-based ensemble La Compagnie des Masques co-founded by Claude Maritz and Giorgio Strehler who, by this point, had left the company. In the previous season, Maritz had staged Thornton Wilder’s Our Town in Geneva and when the production visited Paris it became a big success with over 200 performances,4 a springboard that Maritz attempted to use and, ultimately unsuccessfully, forge a career for himself in France (Bengloan 1994: 147). In 1947, the Compagnie des Masques was invited to produce La Ménagerie de verre at the illustrious Théâtre du Vieux-Colombier. Founded in 1913 by the avant-garde theatre artist Jacques Copeau, the Vieux-Colombier quickly became a haven for artistic experimentation far removed from naturalistic aesthetics and the commercial ethos and exaggerated acting style of many boulevard theatres. It is noteworthy that Williams’ intimate memory-play had its French opening at such a renowned playhouse, lending it impressive cultural cachet and providing for potentially excellent conditions to make an impression on both audiences and critics.

The décor was simple: the house right side of the stage was dominated by the gramophone player and Laura’s collection of glass animals; house left was occupied by the sofa bed and fire staircase. A curtain upstage indicated the remaining rooms of the Wingfield apartment and the famous photograph of the absent family father hung on a wall in this area. Maritz not only directed the play but also designed the lighting and performed the part of Tom. He emphasized the dialogue’s humoristic dimensions and used the recurring rants by Amanda, played by Jane Marken, and her numerous confrontations with Tom to great comedic effect (Figure 1).5 To mark the various temporal layers of the play, Maritz worked with dramatic lighting effects, which proved to be rather unsubtle. For example, he lit up the portrait of the absent father every time the character was mentioned, a device deemed ‘puerile’ (Alter 1947) and ‘childish’ (Augagneur 1947). Reviewers were also unimpressed by Maritz’s acting talents and complained about his ‘false simplicity [and] pretentions’ (Gaillard 1947). They further ridiculed his Swiss accent, flawed diction and struggle with diphthongs (Gaillard 1947; Kemp 1947b) as well as his tone of voice, said to be reminiscent of a ‘funeral director’ (Augagneur 1947).6

Critical reaction to the play was significantly more mixed than it had been in Sweden – an early sign that it would be harder for Williams to conquer the French market. The weekly newspaper Les Nouvelles littéraires appreciated the acting, but dismissed the actual drama as a minor effort (Marcel 1947). Les Lettres françaises found the first act to be positively boring and unfavourably compared the character Tom to the narrator in Our Town. The second act was reviewed in a more favourable light, in particular the long scene between Laura and the gentleman caller played by Daniel Ivernel (...