- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

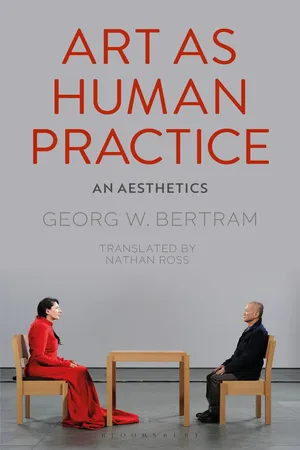

About this book

How is art both distinct and different from the rest of human life, while also mattering in and for it? This central yet overlooked question in contemporary philosophy of art is at the heart of Georg Bertram's new aesthetic. Drawing on the resources of diverse philosophical traditions – analytic philosophy, French philosophy, and German post-Kantian philosophy – his book offers a systematic account of art as a human practice. One that remains connected to the whole of life.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

A critique of the autonomy paradigm

Normally, the philosophy of art begins with the problem of what makes art special. This is a plausible place to start since we want to know what makes art what it is. The question ‘What is art?’ seems to call for an answer that isolates it from other objects and other practices. Thus, philosophical treatments of art seek to grasp the defining quality of art by analyzing what is special about aesthetic qualities, aesthetic experiences, aesthetic practices or aesthetic institutions. This way of proceeding hides a danger: It threatens to make the distinctiveness of art into the decisive feature of how we conceive of it. There is the danger that we take for granted that art can be defined by distinguishing it from other objects, experiences, practices, or institutions. On occasion, philosophers have used the notion of “aesthetic difference as a way of calling our attention to this very assumption.”1 By emphasizing exclusively the particularity of art, philosophy has sought the distinct nature or internal law of art. In short, one thinks of autonomy as the essential feature of art.

I introduce the notion of the autonomy paradigm to describe those approaches that share these assumptions in the broadest sense. Up to this point, I have not yet given a very sharp formulation of the assumptions that I have in mind, let alone a full explanation of them. This is why I will first treat this notion of the autonomy paradigm as a search term that I understand in the following way: All positions belong to the autonomy paradigm that seek to understand art by way of its particularity and by isolating it from other things. Such an approach is more pervasive than one might imagine. Many philosophical positions on art do not speak explicitly of aesthetic autonomy, of art’s internal laws, of separating art, and the like. One might thus think that only a small portion of the debates in philosophy of art and art theory center around this notion of autonomy. But that is not the case. There are many more positions indebted to the autonomy paradigm than just the ones that explicitly use the term autonomy or a related one. Many theories of art take it for granted that art is something particular, distinct, and I want to show that it is just this presumption that is problematic.

Now I do not propose that we can flatly reject the notion that art is autonomous, since it does contain a kernel of truth. But I claim that this kernel of truth does not get thought out in the proper manner, because one tends to understand autonomy from only one side. In critiquing the autonomy paradigm in the philosophy of art, we cannot simply take leave of the notion of autonomy altogether. Instead, it is a matter of taking leave of a one-sided notion of autonomy in order to be able to articulate the true core of this concept. This implies that art is no longer taken as something special and different because of its autonomy in relation to other things. Such a notion of autonomy must be rejected. Instead, I will demonstrate that we have to define what is distinctive about art in the context of human practice, and indeed, take this specificity as an essential aspect of the contribution that it makes to human practice. To put it abstractly: The autonomy of art is constitutively bound up with its heteronomy. This is exactly what I want to reveal through a critique of the autonomy paradigm.

Now it will not be possible here to give a comprehensive discussion of all those positions that belong to the autonomy paradigm. It would also have little sense, since such notions come up in so many different theoretical contexts. For this reason, it behooves us to proceed by way of a few exemplary cases. I will take two examples that are in many respects as far as thinkable from one another. The first position originates from debates about aesthetic education. Over the last thirty years, many, especially in the German-speaking world, have sought to understand the specific nature of art in terms of aesthetic experience, often taking Adorno as an inspiration. In doing so, these thinkers take Adorno’s notion of aesthetic autonomy for granted, and this includes Christoph Menke’s philosophy of art, which I will deal with as an exemplary case. Menke articulates, in an especially consistent way, the thought that the autonomy of art manifests itself in special kinds of experiences.

The second position that I will take as exemplary belongs to the tradition of analytic philosophy of language. Due to failures in both the anti-essentialist2 and the essentialist3 approaches to art, and under the influence of the pragmatic tradition,4 the analytic tradition has continuously sought to define art with recourse to its historic and cultural context. Arthur Danto is a prime example of someone who advocates for such an approach in a particularly well-thought-out manner. He defines art essentially in terms of artworks that represent a particular challenge to the institution, indeed to the very concept of art, such as Marcel Duchamp’s ready-mades or Andy Warhol’s pop-art. Danto has been especially critical toward any notion of art that defines it merely through a theory of the institution, as George Dickie had suggested.5 Danto brings to the fore the aspect of art that has meaning, as opposed to a narrowly pragmatic understanding of art, and explains its societal context in such a way. This requires him to make a distinction between artworks and other kinds of objects (such as signs) that have meaning. And for just this reason, I will argue that even he is an advocate of the autonomy paradigm.

Thus, by examining Menke and Danto and illuminating the underlying parallels in their seemingly very different positions, I will seek to illustrate what I mean by the autonomy paradigm so as to give an overview of the greater theoretical context from which my own approach will depart. I especially want to consider certain simplifications that result out of the autonomy paradigm. These simplifications will become apparent if we consider philosophies of art in terms of two determining factors that belong to each of them: that of art’s specificity and that of its value. By determinations of the value of art, I mean those that make art comprehensible as a valuable practice. Because of the way philosophy tends to pose problems, either it defines the value of art through its specificity or it makes the definition of art irrelevant to its value. Neither of these two approaches succeeds in seeing the specific nature of art as an aspect of its value, since they both take the essence of art as independent of its value. This diagnosis should make it possible to find an approach to art that does not oversimplify.

1.Art as a different good: Menke

If we ask what is specific to art, then one of the things that comes to mind is the special set of experiences that we have in dealing with artworks.6 These experiences seem to distinguish themselves from all other experiences in some respect. They thus seem to offer a good point of entry if we want to figure out what is special about art. Correspondingly, we can say: Art is a practice in which we have certain experiences, and artworks are the objects or events that make these specific experiences possible. If we follow this line of thought, then we can ask what is specific to aesthetic experiences in this sense. The answer might be: In dealing with artworks, we do not simply have an experience like any other. It is far more the case that the very process of experience comes into the foreground. A plausible reason for this is that something here does not function in such a frictionless manner as in other cases. Our everyday experiences are mostly marked by a frictionless interaction with various types of objects. We have command over many routines and habits that allow us to come to terms with objects. Precisely these habits and routines are what get called into question by art. This calling into question of habitual ways of dealing with things is what would make up the specific nature of aesthetic experience.

This argument might seem quite plausible. It is thus no wonder that this argument finds a very developed and convincing advocate in the philosophy of Christoph Menke. Since his monograph The Sovereignty of Art was first published in 1988, Menke has defended a position that understands aesthetic experience as leaving behind the ordinary and everyday way of dealing with things. With this explanation, he takes up Adorno’s negative dialectics7 and gives it a practical turn. Where Adorno understands artworks as objects that close themselves off to communication (as he articulates under the notion of the “enigmatic quality”—Rätselhaftigkeit—of art),8 Menke understands them as objects that initiate a kind of communication marked by irritation.

He describes this irritation in The Sovereignty of Art as one that occurs within the use of signs. The experiences that artworks make possible are, in Menke’s account, experiences of interacting with objects that have a meaning to us. This premise makes sense: We can very well conceive of artworks as objects that have a meaning for us. Menke goes on to say that what characterizes these objects is that we cannot reveal their meaning in a simple, straightforward manner. Artworks confront us with a material whose meaning is not accessible in a straightforward manner.9 The emergence of meaning comes to a standstill in them. Menke develops this notion of standstill through that of reading. In developing a “reading” of an artwork, we come upon aspects of the work that we cannot integrate. This entails that we constantly have to find new approaches. Recipients increasingly have the experience in dealing with artworks that they are dealing with a material whose meaning they cannot reveal. We are dealing, he argues, with the experience of a sign usage that does not function: Artworks suspend the automatic transition from sign to meaning,10 and in doing so, they leave space for a special experience that Menke calls “de-automatization.”11 As a special kind of sign, artworks interrupt the way in which we automatically interact with signs in our everyday life, and they reveal the conditions under which the use of signs normally stands. In later works, Menke elaborated on this approach from The Sovereignty of Art. In his study Force, he implicitly admits that we cannot fully explain the value of the aesthetic by taking it as a practice that reveals the conditions of how we ordinarily use signs. It is not at all clear what it means for the ordinary sign usage to have such an experience,12 and this means that it is necessary to elaborate on the specific provocation that is entailed by this experience. Menke provides such an elaboration by specifying that the value that accrues to aesthetic practice by suspending ordinary sign usage consists in the fact that it is an expression of force (Kraft). He argues that aesthetic practice is characterized by a particular kind of liveliness, that it is a particularly lively mode of action to attend to artworks and aesthetic events. And for this mode of action, he writes the following: “Human action, as living action, is not the realization of a purpose but the expression of force.”13 Menke understands the force that he has in mind here, with reference to Nietzsche and Herder, as the basis of life itself. When it manages to express itself, life is coming into its own in a special way, with a special vivacity that cannot be subjected to a particular end. For Menke it is thus characteristic of aesthetic practices and of the experiences gained from these practices that the purposiveness of ordinary actions gets suspended. This is how the notion of de-automatization comes into play again, as the rupture of the automatic elements of everyday life. In Force, he designates this as “not being able” (Nichtkönnen). For Menke, it is decisive for breaking out of ordinary automatization that practice not be governed, to use a theme from Adorno to explain Menke. This allows us to define aesthetic practice in yet another way: as a kind of nongoverned practice, as a practice of not being able. Correspondingly, he writes: “Artists are able to be not able” (können das Nichtkönnen).14

Menke nevertheless claims that art initiates a different mode of practice within the domain of human practical activity. He calls this new mode “aestheticization.”15 By being aestheticized, activities that are otherwise subject to routine and habit come to be carried out in a non-habitual and nonroutine way. This makes it clear that habits and routines give us a false semblance of being able to determine ourselves and determine the world. So aestheticizing rests on non-aesthetic practices, which it nevertheless transforms by bringing the forces to the fore on which these practices rest. Thus, aestheticizing infects everyday practice with another mode, and human practice becomes split within itself. When an act of aestheticizing takes place, then we see a gulf open up between normal human practices on the one hand that are mired in habit and routine, and those on the other hand that reveal those forces in which all habits and routines show themselves to be something different from what they appear to be. The determinateness of everyday life gets confronted with an indeterminate play of forces.

This short summary has not nearly exhausted Menke’s position. However, we can recognize its basic trajectory. It represents a very-well-thought-out attempt to define the specificity of aesthetic practice in and through the form of autonomy that realizes itself in this practice. This practice is autonomous as a practice of “not being able,” as a practice of indeterminacy, or to put it structurally, as a practice of rupture (in the sense of a transformation—Menke also speaks constantly of a “regression”16 ). He interprets this practical rupture as the basis of what makes aesthetic experiences special, and he also uses this to determine the value of art. In Force, he speaks of a special form of the good that gets realized in art: life in its liveliness. This good does not allow itself to be integrated into the goods of purpose-oriented action, but instead is supposed to serve as its basis. Purposiveness in human actions is only possible when human life is not completely determined from without, when there is a certain basic indeterminacy. To put it another way: All human abilities rest on a certain “not being able.” It is just this “not being able” that gets reinvigorated by aesthetic practices, and the aesthetic is thus revealed as a motor for new kinds of practice.

On the basis of all of this, we can say that Menke has two theoretical moves: First, he designates the specificity of art in terms of its autonomy. Then he introduces the idea that art has a special value in relation to other human practice. Before I transition to a critical account of this approach, I want to draw out these two basic moves and their underlying theses:

Menke’s Specificity Thesis: Art brings about a rupture with everyday practices by initiating a practice of “not being able.” This practice is autonomous, in distinction to those that take place in habits and routines.

Menke’s Value Thesis: The practice of “not being able” has the value i...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Dedication

- Also available from Bloomsbury

- Title Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 A critique of the autonomy paradigm

- 2 From Kant to Hegel and beyond

- 3 Autonomy as self-referentiality—the practical reflection of art

- 4 Art as practice of freedom

- Bibliography

- Copyright Page

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Art as Human Practice by Georg W. Bertram, Nathan Ross in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Art Theory & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.