![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Textiles

TOVE ENGELHARDT MATHIASSEN

To what extent can we talk about a fabric or dye as being “enlightened”? This intriguing question will be addressed here. From an art historical perspective, the years from 1650 to 1800, the Age of Enlightenment, encompass the baroque, the régence (French period of regency style), rococo, and the first neoclassical styles. When applied to fashion and fabrics, these stylistic approaches are different in almost every aspect, be it textile design, the preferred fibers used for dress, or the favored colors. Looking at deeper social and technical processes, during the 150 years in question, manufacturing methods and the lives of people involved in the production of these goods went through massive changes too. Closely related to these social conditions, access to fashionable fabrics and other materials used in garment construction changed conspicuously from 1650 to 1800.

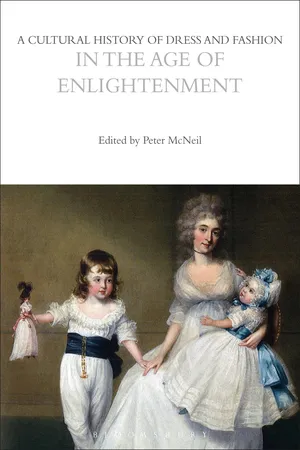

We will start at the end of the period, by considering what is perhaps the most obvious outcome of the Enlightenment when it comes to fashion, the neoclassical “robe en chemise.” In Denmark the classic and first-known example1 is the 1787 painting by the famous Danish painter Jens Juel (Figure 1.1).2

The story of its creation reveals interesting aspects of the link between morality and fashion towards the end of the eighteenth century. The painting is of Duchess Louise Augusta, half-sister of the later Danish king, Frederik VI. She was called “la petite Struensee,” even at court, because she was the result of a love affair between Queen Caroline Mathilde and the king’s personal physician, Johan Friedrich Struensee.3 She was born in 1771, her older half-brother in 1768. In spite of her paternity, Princess Louise Augusta held an elevated position at court and married the duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Sønderborg-Augustenborg in 1786. Her husband wanted his wife to be portrayed in the newly fashionable “robe en chemise.” This was a thin tubular dress with links to both juvenile and also Creole dressing. People were not used to seeing European women wearing such clothes. The artist Juel was very uneasy about the commission and the highest-ranking court official Johan Bülow was virtuously indignant, for to the contemporary eye this type of dress had very obvious connotations of being akin to underwear. Bülow recorded the awkward prelude in his diary, January 3, 1786:

Professor Juel, Court Painter, brought to me Esquisse for a Portrait of Princess L. Augusta painted as a Greek Nymph, I said that it was not a decent Dress, in which he agreed and wished that he was allowed to make it differently but that he has had express Commands from the Crown Prince and the Prince of Aug. to do it in this Way.4

Bülow tried to explain to the crown prince that it was improper to have his sister portrayed in her undergarments. The crown prince objected and got angry when Bülow commented: “You have just Actresses and your Mistress painted like that, but a Princess! and Juel has the same Idea as I and so certainly have many others.” HRH Frederik broke off the conversation and ordered that Bülow read from the dispatches. The case also brings to mind the famous scandal regarding Queen Marie-Antoinette, who was painted by Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun in the chemise à la gaulle or chemise à la reine (Figure 3.16), a fashionable muslin dress so scanty that the work was taken down at the Salon of 1783 and replaced with a new version in which the Queen wore a conventional silk dress with tightly fitted sleeves.

FIGURE 1.1: Duchess Louise Augusta in her “robe en chemise,” Jens Juel, 1787. The Museum of National History, Frederiksborg Castle, Denmark.

The loose-fitting dress, which pulled over the head, was indeed a daring example of the novel neoclassical garment for women of the late Enlightenment. The gown brought to mind a Greek nymph in thin, transparent fabrics that originally were likely “Coan” silks rather than cottons, but that for the late eighteenth century were either made of fashionable cottons like high-quality muslins as well as light dress silks.5 In Louise Augusta’s case, she also wore a fine, white gauze veil striped with closer-set warp threads along the edges in her coiffure, the same sort of edging to her collar, and had sleeves of very thin fabrics. In theory, such an outfit meant that she was able to dress herself without the help of a lady’s maid—a dramatic departure from the demands of earlier dress styles. She could also wear this dress without stays—a very risqué choice indeed in the eyes of her contemporaries, and again one that represented the beginnings of a massive shift in fashions and sensibility. Her “enlightened” dress, therefore, allowed her and other fashionable women to be self-reliant and to move without the bodily restraint of stays. Not only could they be independent while dressing, most women would possess the skills needed to sew such clothes themselves—if they so desired—without the help of professional tailors and dressmakers. It was indeed a revolution in fashion.

THE STORY OF FIVE TEXTILES

This chapter proceeds by “unpacking” some of the myriad textile terms familiar to an eighteenth-century consumer, but little known outside expert circles today. Established in 2004, the objective of the Danish research project Textilnet is to make a historical and contemporary digital dictionary or term base available (at www.textilnet.dk) to preserve and communicate the cultural heritage of concepts for dress and textiles. The hand written and typed records of two Danish researchers, Dr. Erna Lorenzen and Ellen Andersen, were the starting point of the project. From 1959 to 1979, Erna Lorenzen was curator of dress and textiles at Den Gamle By, the National Open Air Museum of Urban History and Culture,6 and from 1936 to 1966, Ellen Andersen held a similar position at the National Museum of Denmark. Every term in the database based on their research is supported by evidence from scientific literature, dictionaries and other such handbooks.7 When compiled from these sources, the terms for textiles dated before 1807 number around 1,000. It would be impossible in the scope of this volume to publish or describe all of them. Instead, I will discuss five textiles from Textilnet that are significant for, or typical of, the period under study, and complement their discussion with the evidence of material artifacts in the collections of Den Gamle By as well as some comparative material. Doing so will give an impression of the abundance of fabric types available to the “enlightened costumer,” and also of the place of textiles within the economy and within networks of trade. Through these five different examples, therefore, we can glimpse the global connections in the dress and fashion of this period, the social conditions that shaped their production and use, and also the key changes in textiles at this time.

It is important to underline that in the eighteenth century, every textile was made of either plant or animal fibers, or, as was quite often the case, of mixed fibers, including also metal threads of different kinds. The fabrics for discussion are, using the names by which they were known in Denmark: Abat de Macedoine (a coarse woolen), Drap d’or (a luxurious cloth), flandersk lærred (flax), chintz (printed cotton), and kastorhår (felted beaver). Between them they cover the main textile types of the long eighteenth century: woolens, silk, linen, cottons, and prepared fur.

In the textile Abats or Abat de Macedoine8 we find embedded the history of slavery and global networks in a condensed form. The term is found in two Danish encyclopedias of merchandise: Juul, dated 1807,9 and Rawert, dated 1831.10 Both encyclopedias are examples of the Enlightenment drive to order phenomena in categories, and to systematize and diffuse knowledge. Rawert’s definition runs as follows:

Abat de Macedoine, a sort of coarse, woolen fabric for clothing of poor people; furthermore for wrapping, especially of tobacco. Considerable amounts were earlier sent from Smyrna [now called Izmir] via Marseilles to West India to use for clothing of negroes (p. 2).

In stating that the same coarse fabric was suitable both for the wrapping of tobacco and for the clothing of slaves and poor people, this example makes it abundantly clear that the world of textiles was always integrated with social history. While a technical explanation of the fabric is not available in this example—and neither Florence Montgomery nor Elisabeth Stavenow-Hidemark11 give a definition or analysis of Abat de Macedoine—it nevertheless emerges clearly that this term has a French origin, which is common in Danish eighteenth-century expressions for dress and textiles.12 Rawert further informs us that abats are a sort of coarse fabric from Macedonia, sold in Turkey, Italy, and partially in France; he then gives the information about clothing the slaves in the West Indian colonies. Until they were sold to USA in 1917, Denmark owned the West Indian islands of Saint Croix, Saint John and Saint Thomas, and some uninhabited smaller islands. Abats could not be defined as fashionable fabrics in the sense that people of fashion would wear them, but considering the economic system of their production, abats show us how the expenses of clothing the cheap labor force were kept as low as possible, and that it was seen as profitable in a global network of trade to weave coarse, low-quality fabrics in southeastern Europe and transport them across the Atlantic Ocean. Abats were not alone in being sold in the West Indies. Cheaper cotton goods, as for example Guinea cloths and chelloes—rough fabrics that were either striped or checked—also found a market (Figure 1.2).13

“Guinea cloths,” too, played a somewhat grim role in the global market and consumption of textiles, and in the history of humans as cheap labor in the colonies. Guinea cloths and other types of cotton fabrics were purchased in India and resold in West Africa in exchange for slaves, who were then forced to travel across the Atlantic to work in the plantations in the Americas.14 In a grim irony, some of these plantations were producing cotton.15

While Abat de Macedoine was a low-quality woolen fabric, already in the pre-modern period Europe was producing exquisite fabrics made of wool. Fragments of textiles from the northern part of Europe indicate an organized production of woolen cloth as early as the Hallst...