![]()

Part I

Academic vocabulary

‘Academic vocabulary’ is a term that is widely used in textbooks on English for academic purposes and Second Language Acquisition (SLA) reference books. Nevertheless, it can be understood in a variety of ways and used to indicate different categories of vocabulary. In this section, my objectives are to clarify the meaning of ‘academic vocabulary’ by critically examining its many uses, and to build a list of words that fit my own definition of the term. Chapter 1 therefore tries to identify the key features of academic vocabulary and to clear up the confusion between academic words and other vocabulary. Chapter 2 proposes a data-driven methodology based on the criteria of keyness, range and evenness of distribution, and uses this to build a new list of potential academic words, viz. the Academic Keyword List (AKL). This list is very different from Coxhead’s Academic Word List and has already been used to inform the writing sections in the second edition of the Macmillan English Dictionary for Advanced Learners (see Gilquin et al., 2007b). The AKL is used in Section 2 to analyse EFL learners’ use of lexical devices that perform rhetorical or organizational functions in academic writing.

![]()

Chapter 1

What is academic vocabulary?

Academic vocabulary is in fashion, as witnessed by the increasing number of textbooks on the topic. Recent titles include Essential Academic Vocabulary: Mastering the Complete Academic Word List (Huntley, 2006) and Academic Vocabulary in Use (McCarthy and O’Dell, 2008). But what is academic vocabulary? The term often refers to a set of lexical items that are not core words but which are relatively frequent in academic texts. Examples of academic words include adult, chemical, colleague, consist, contrast, equivalent, likewise, parallel, transport and volunteer (cf. Coxhead, 2000). Unlike technical terms, they appear in a large proportion of academic texts, regardless of the discipline. Academic vocabulary is also sometimes used as a synonym for sub-technical vocabulary (e.g. mouse, bug, nuclear, solution) or discourse-organizing vocabulary (e.g. cause, compare, differ, feature, hypothetical, and identify). In this chapter, I set out to review the many definitions of academic vocabulary that have been given and to clear up the confusion between academic words, core words, technical terms, sub-technical words and discourse organizing words. I will show why a definition of academic vocabulary that excludes the top 2,000 words of English is not very useful for productive purposes in higher education settings and argue for a function-based definition of the term. The very existence of academic words has recently been challenged by several researchers in English for Specific Purposes (ESP) who advocate that teachers help students develop a more restricted, discipline-specific lexical repertoire. I will round off this chapter by situating the book in ongoing debates over generality vs. disciplinary specificity in teaching vocabulary for academic purposes.

1.1. Academic vocabulary vs. core vocabulary and technical terms

Numerous second language acquisition studies have investigated whether there is a threshold which marks the point at which vocabulary knowledge becomes sufficient for adequate reading comprehension. Laufer (1989; 1992) has shown that at least 95 per cent coverage is needed to ensure reasonable comprehension of a text. To achieve this coverage, it is commonly believed that students in higher education settings need to master three lists of vocabulary: a core vocabulary of 2,000 high-frequency words, plus some academic words, and technical terms. Some researchers, however, do not agree that vocabulary categories can be described as if they were clearly separable. In this section, the notions of core vocabulary, academic vocabulary and technical terms are described and illustrated. The criticisms levelled at the division of vocabulary into mutually exclusive lists are then reviewed.

1.1.1. Core vo cabulary

A core (or basic or nuclear) vocabulary consists of words that are of high frequency in most uses of the language. It comprises the most useful function words (e.g. a, about, be, by, do, he, I, some and to) and content words like bag, lesson, person, put and suggest. Stubbs describes nuclear words as an essential common core of ‘pragmatically neutral words’ (1986: 104) and lists five main reasons for their pragmatic neutrality:

1. Nuclear words have a ‘purely conceptual, cognitive, logical or propositional meaning, with no necessary attitudinal, emotional or evaluative connotations’ (ibid.).

2. They have no cultural or geographical associations.

3. They give no indication of the field of discourse from which a text is taken, i.e. its domain of experience and social settings.

4. They are also neutral with respect to tenor and mode of discourse: they are not restricted to formal or informal usage or to a specific medium of communication, e.g. written or spoken language.

5. They are used in preference to non-nuclear words in summarizing tasks.

The best-known list of core words is West’s (1953) General Service List of English Words (GSL),1 which was created from a five-million word corpus of written English and contains around 2,000 word families. Percentage figures are given for different word meanings and parts of speech of each headword. In a variety of studies, the GSL provided coverage of up to 92 per cent of fiction texts (e.g. Hirsh and Nation, 1992), and up to 76 per cent of academic texts (Coxhead, 2000). Next to frequency and coverage, other criteria such as learning ease, necessity and style were also used in making the selection (West 1953: ix–x). West also wanted the list to include words that are often used in the classroom or that would be useful for understanding definitions of vocabulary outside the list. The GSL has had a wide influence for many years and served as a resource for writing graded readers and other material.

A number of criticisms have, however, been levelled at the GSL, most particularly at its coverage and age. Engels (1968) criticized the low coverage of the second 1,000 word families. While the first 1,000 word families covered between 68 and 74 per cent of the words in the ten texts of 1,000 running words he analysed, the second set of word families in the GSL provided coverage of less than 10 per cent. In addition, because of changes in the English language and culture, the GSL includes many words that are considered to be of limited utility today (e.g. crown, coal, ornament and vessel) but does not contain very common words such as computer, astronaut and television (see Nation and Hwang, 1995: 35–6; Leech et al., 2001: ix–x; Carter, 1998: 207). However, several researchers have pointed out that, for educational purposes, it still remains the best of the available lists because of ‘its information on frequency of each word’s various meanings, and West’s careful application of criteria other than frequency and range’ (Nation and Waring 1997:13).

1.1.2. Academic vocabulary

A number of academic word lists have been compiled to meet the specific vocabulary needs of students in higher education settings (e.g. Campion and Elley, 1971; Praninskas, 1972; Lynn, 1973; Ghadessy, 1979; Xue and Nation, 1984). The Academic Word List (Coxhead, 2000) is the most widely used today in language teaching, testing and the development of pedagogical material. It is now included in vocabulary textbooks (e.g. Schmitt and Schmitt, 2005; Huntley, 2006), vocabulary tests (e.g. Schmitt et al., 2001), computer-assisted language learning (CALL) materials, and dictionaries (e.g. Major, 2006).

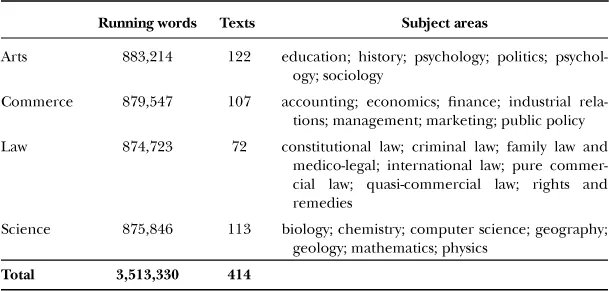

The Academic Word List (AWL) was created from a corpus of 414 academic texts by more than 400 authors and totals around 3.5 million words. The Academic Corpus includes journal articles, chapters from university textbooks and laboratory manuals. It is divided into four sub-corpora of approximately 875,000 words representing broad academic disciplines: arts, commerce, law and science. Each sub-corpus is further subdivided into seven subject areas as shown in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Composition of the Academic Corpus (Coxhead 2000: 220)

Like the General Service List, the Academic Word List is made up of word families. Each family consists of a headword and its closely related affixed forms according to Level 6 of Bauer and Nation’s (1993) scale, which includes all the inflections and the most frequent and productive derivational affixes. For example, the words presumably, presume, presumed, presumes, presuming, presumption, presumptions and presumptuous are all members of the same family.

Coxhead (2000) selected word families to be included in the AWL on the basis of three criteria:

1. Specialized occurrence: a word family could not be in the first 2,000 most frequent words of English as listed in West’s (1953) General Service List.

2. Range: a word family had to occur in all four academic disciplines with a frequency of at least 10 in each sub-corpus and in 15 or more of the 28 subject areas.

3. Frequency: a word family had to occur at least 100 times in the Academic Corpus.

The resulting list consists of 570 word families and covers at least 8.5 per cent of the running words in academic texts. By contrast, it accounts for a very small percentage of words in other types of texts such as novels, suggesting that the AWL’s word families are closely associated with academic writing (Coxhead, 2000: 225). It is divided into 10 sublists ordered according to decreasing word-family frequency. Some of the most frequent word families included in Sublist 1 are headed by the word forms analyse, benefit, context, environment, formula, issue, labour, research, significant and vary. Examples of the least frequent word families in Sublist 10 are assemble, colleague, depress, enormous, likewise, persist and undergo.

Academic words are likely to be problematic for native as well as non-native students as a large proportion of them are Graeco-Latin in origin and refer to ...