This is a test

- 184 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

How are love and emotion embodied in material form? Love Objects explores the emotional potency of things, addressing how objects can function as fetishes, symbols and representations, active participants in and mediators of our relationships, as well as tokens of affection, symbols of virility, triggers of nostalgia, replacements for lost loved ones, and symbols of lost places and times. Addressing both designed 'things with attitude' and the 'wild things' of material culture, Love Objects explores a wide range of objects, from 19th-century American portraits displaying men's passionate friendships to the devotional and political meanings of religious statues in 1920s Ireland.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Love Objects by Anna Moran, Sorcha O'Brien in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Design & Design generale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

SECTION 1

The Lives of Objects

1

‘I Love Giving Presents’

The Emotion of Material Culture

Introduction: a given thing

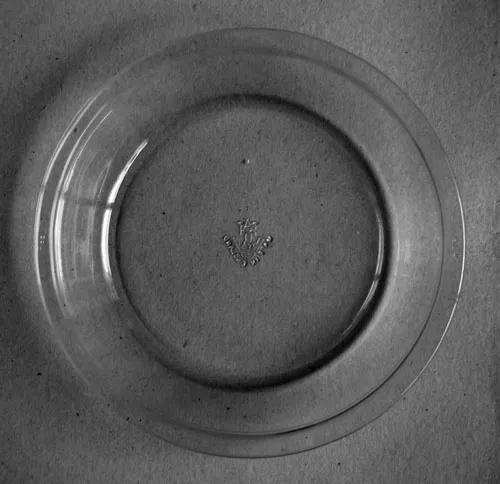

People become attached to things. ‘All my presents hold fond memories for me’, wrote a retired Post Office worker of the wedding gifts she received in 1954. Indeed, she held onto her gifts in order to remember. ‘I love to take things out of a cupboard and think back to the donor, relative or friend, many long gone’ (M1571).1 The desire to have wedding gifts near at hand is also expressed by a former nurse, married in 1963: ‘I am very attached to my remaining wedding presents and if I have to move to a smaller place because of old age I shall do my utmost to take them with me’ (L1991). Attachment is not an abstract preference. Things must be kept and kept close to the person. This is often expressed in the same way. ‘I would not part’, begins a lecturer, ‘with the bone china teaset as it holds quite dear memories of the old couple who are now dead’ (S1383). She received the china from her in-laws in 1960. A factory worker, who kept all her wedding presents, including Pyrex dishes not yet put to use 30 years after her wedding, repeats the phrase: ‘I WOULDN’T PART WITH THEM FOR THE WORLD’ (C2579) (see Figure 1.1).

The retired Post Office worker, the former nurse, the lecturer and factory worker are Mass Observation writers. This chapter is based on readings of their writings, collected by the Mass Observation Archive; their writings are but a small portion of this Archive’s unique records of everyday life (Sheridan et al., 2000). The retired Post Office worker, the former nurse, the lecturer and factory worker are four of the thousands of people who have joined the Mass Observation panel of writers between 1981 and today; they have all corresponded with the Archive for over 10 years on multifarious matters of everyday life or those effecting it: from body decoration to the bombing of Iraq; shopping to sex. I have read their words to find the meanings of a material culture of domesticity (Purbrick, 2007) and would suggest that their writings can be considered documents of the emotion of material culture. Mass Observation writers do not set out to address the changing agendas of academic inquiry, such as the current concern with affect or emotion, but make an altruistic attempt to respond to the open-ended questions that make up Mass Observation directives, such as those included in a Giving and Receiving Presents directive sent out in Autumn 1998 on which this chapter is based. They do, however, reflect upon the practices of everyday life.2 They document their lives, including the emotional, even affectionate relationships with material forms, especially those that have been domesticated, demonstrating the attachment and affinity between persons and things. This chapter considers the relationships with, through and in the material forms in late twentieth-century Britain. It is a study of the domestic exchanges of objects that make up family life: a study of gifts. But first, a few words about the status of Mass Observation as a source for this study and, second, a few more about the implications of finding emotion in material culture.

FIGURE 1.1 Pyrex ovenware plate, Corning Glassworks. Photograph by Louise Purbrick.

Mass Observation

Mass Observation writing is the subject of methodological and theoretical inquiries in anthropology, sociology, social and cultural history (Bhatti, 2006; Hurdley, 2006, 2013; Pollen, 2013; Purbrick, 2007; Sheridan et al., 2000; Stanley, 2001). The Mass Observation Archive must be one of the most thoroughly debated collections of documents of the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Mass Observation writing, either that generated by its founders Tom Harrison, Charles Madge and Humphrey Jennings through their 1930s documentary collages announced as the ‘anthropology of home’, or that of the hundreds of participants, ‘correspondents’ in the Mass Observation Project ‘recording everyday life in Britain’ (Mass Observation, 2013) initiated in the 1980s, is multivalent: it is meaningful as historical text, sociological data and anthropological material. Few documents tell of everyday life; so many written words, such as these I write here, are shaped by destinations as publications, restrained by the conventions of academic style or by the conventions of individual expression or editorial practices of journalism that eschew the everyday as too obvious to analyse, too routine to ever be newsworthy. Collective recording projects, such as Mass Observation, that generate writing for that purpose only, for the record, are uniquely important; writing is not formulated to achieve institutional targets, to find a market for ideas or to follow fashions in what is supposed to be interesting, worthy of note.

As long ago as 1996, the then Archivist of Mass Observation, Dorothy Sheridan, authored a working paper to address assumptions that Mass Observation was unreliable or unrepresentative and therefore unimportant as a source for academic study (Sheridan, 1996). She countered the criticism that Mass Observation was anecdotal. Drawing on the methodological observations of J. Cylde Mitchell about particular kinds of fieldwork as case studies (Mitchell, 1984), Sheridan developed a theoretical position for Mass Observation as a ‘telling’ case. Its claim to knowledge is not based on the coverage of demographic types, as required by quantitative survey; it is detail, richness or thickness of description that reveals relationships or structures (Geertz, 1993). Such relationships and structures are inevitably specific – they are specific cases – but it is from specific cases that generalizations, propositions or theories can be made and tested. Thus, the Giving and Receiving directive may not provide evidence of how many gifts of what type are given (a retailing stock-take would do that job far better), however, it might tell much more about the significance of giving as a practice, regardless of the type of gift. Through the Giving and Receiving directive, Mass Observation writers explain why they give gifts, thus a theory of practice of everyday life is produced by those who live that life.

Emotion in material culture

To consider material forms as repositories of affection and not just desire, of longing as opposed to preference, of love of all kinds, demands some rethinking of the status of objects in capitalist and consumer culture. Such feelings show the limits of commodity worlds. If a thing can create affection, then the illusion of human fulfilment falsely promised in the marketplace might actually be real: a fairytale can come true. For Marx, there is no such happy ending. His critique of the commodity, and its subsequent development into a comprehensive and convincing analytical assault upon cultures of consumption, rests upon the fact that the commodity cannot be redeemed from its state of alienation (Marx, 1988, pp. 125–177; Slater, 1997, pp. 63–99). Commodities are empty of all but market values; exchangeable for anything of momentarily equivalent, arbitrary and also empty value, such as money; they are alienated from the moment of being made. A past existence in production is expediently forgotten in the act of exchange, but, even if remembered, there is no redemption in production. Commodities are formed through the calculated productive capacities of a labour force; the labour of those who comprise that force is measured to become as exchangeable and alienated as a commodity. The commodity is a disembodied form, which through repeated exchange, has reproduced a pervasive culture of acquisition and loss. Commodity exchanges determine all other forms of exchange, including those between people beyond their place in production: relationships are commodified, the human condition standardized with only ‘the freedom to choose what is always the same’ in Theodor Adorno’s oft-quoted summary. He also remarked, ‘We are forgetting how to give presents’ (Adorno, 1997, p. 42).

The dominance of the commodity caused this forgetfulness. Commodities subsume everything; they make all things in their image, including gifts. That something exists outside what Adorno terms the ‘exchange principle’, the quick transfer of one for another, an article for money, is ‘implausible’. Giving appears to be selling. ‘[E]ven children eye the giver suspiciously’, observes Adorno, ‘as if the gift were merely a trick to sell them brushes or soap’ (Adorno, 1997, p. 42). Thus, the calculating logic of the commodity exchange is imposed upon gift exchange. Calculation is not only the process through which a commodity acquires its price, purchasers also estimate the object as a matter of loss or gain. What will it cost me? Is its value to me worth its price? Will its cost prevent me from getting something better? Adorno sees commodity calculation entering gift relations. Estimation of exchange begins the decline of giving. ‘[H]ardly anyone’ is now able to give:

At best they give what they would have liked themselves, only a few degrees worse. The decay of giving is mirrored in the distressing invention of gift articles, based on the assumption that one does not know what to give because one does not really want to. This merchandise is unrelated like its buyers. It was a drug in market from the first day. Likewise, the right to exchange the article, which signifies to the recipient: take this it is all yours, do what you like with it; if you don’t want it, it is all the same to me, get something else instead.

Adorno, 1997, p. 42

The gift article is the commodity in its pure form (see Figure 1.2). It has an ‘unrelated’ character. Because it belongs unequivocally to the receiver (‘it is all yours’) and can be used for exchange and even disposed of. It cannot, therefore, be a gift. The gift article cannot create relationships; it denies the connection between people who ought to be established through their material exchanges. These articles demonstrate the reduced conditions of life in capitalism. Those who do not give, or do not give properly, become dehumanized as individuals. ‘In them wither the irreplaceable faculties which cannot flourish in the isolated cell of inwardness, but only in live contact with the warmth of things’. This is a kind of death. ‘A chill descends on all they do’ and ‘recoils on those from whom it emanates’. He who does not give ‘makes himself a thing and freezes’ (Adorno, 1997, p. 43).

However, the retired Post Office worker does remember how to conduct gift exchanges: ‘After all these years it is difficult to remember some of our presents but I’m happy to say we still have many of them and I still associate the giver with the gift when we use them’ (M1571). Indeed, she honours the gift in exactly the way its theorist, Marcel Mauss, says she should. His 1925 essay ‘The Gift’, turns upon the association of giver and gift. Indeed, it is the gift that creates association. It does so because the giver never quite leaves the gift. Gifts ‘still possess something of the giver’ (Mauss, 1990, p. 12). To receive a gift is to accept the giver along with their offering; it is to allow the giver a part in the receiver’s future, at the moment when the gift is inserted into a life. If the gift is a garment, for example, the giver is present when it is worn; if it is food, they are at the table as the meal is eaten. To accept is to acknowledge the presence of the giver in relation to the receiver. This is the effect (and affect) of what Adorno calls ‘real giving’. Real giving produces a proper human relationship. He explains: ‘Real giving has its joy in imagining the joy of the receiver. It means choosing, expending time, going out of one’s way, thinking of the other as a subject’ (Adorno, 1997, p. 42). A person is recognized in the real gift. In dialectical opposition to an unrelated commodity (and those who exchange it), the gift (and its givers and receivers) is a related thing.

FIGURE 1.2 An example of gift articles in a commercial setting, 2013. Photograph by Louise Purbrick.

Adorno read Marcel Mauss. The work of gifts in societies where gift exchange is the only form of exchange is the subject of Mauss’ essay, but it can be read, indeed it has been read, as a critique of capitalist exchange relations (Carrier, 1995; Gregory, 1982). The commodity transactions of capitalism cannot create human relationships because these transactions have a definite conclusion. A commodity exchange is momentary and is over as soon as an object passes from one hand to another. An exactly equivalent value, most often its price in money, is passed back. A deal is done. Each commodity exchange begins a new brief contract, quickly completed. Thus, commodities create no bonds. Once you have paid the price, you have all rights of possession without regard for another’s past relationship to the object: free to use, alone to have. All is alienated. By contrast, gift exchanges are very slowly, if ever, concluded. Giving is always giving back. The gift, according to Mauss, is an obligatory form, an object that must be given, received and reciprocated. The imperative to reciprocate, which generates giving then receiving, receiving then giving, is because a part of the giver remains with the gift. A given thing encloses a debt to the giver or related person; it creates a bond that can only be relieved by giving another gift, and that serves only to extend the debt. Gifts create cycles of exchange, enforcing solidarities of indebtedness, sustaining communities and societies. Gift transactions are irrevocable and sociable. Gifts bind people together.

Real giving

The writings of the former nurse, retired Post Office worker, factory worker and lecturer illustrate the binding together of people through given things. While the gift exists, is present, so to speak, so is the person of the giver, despite apparent physical absence. Having and holding, looking at or touching, a once given thing can overcome the separation of persons over any distance; it can connect the living and the dead. As the Post Office worker explained, to take wedding presents from a cupboard is to recollect their givers, ‘many long gone’. Or, as the lecturer stated, ‘memories of the old couple who are now dead’ are held in the bone china teaset. These accounts of the attachments of people and things relate to the receipt of gifts, but Mass Observation writers also described their practices of giving. Their responses to the Giving and Receiving Presents directive, record and reflect upon their experience of gift exchange. Both descriptive and analytical, their texts raise the matter of concern to Adorno: is ‘real giving’ still possible? To which I would add the following questions: What is affectionate material culture? Do gifts carry emotion? How can we love objects? Why do we become attached to things? What is the emotion of material culture? But first, what are the patterns of gift exchange?

The Mass Observation correspondent who had worked as a nurse, who also introduces herself as a ‘widow’, writes:

As with most people my main present giving is for Christmas and birthdays. I have a small family to give to: on the English side – daughter, son and recently his fiancé, brother, sister in law, nie...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Notes on contributors

- Editors’ foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: How Do I Love Thee? Objects of Endearment in Contemporary Culture

- SECTION 1: The Lives of Objects

- SECTION 2: Projecting and Subverting Identities

- SECTION 3: Objects and Embodiment

- SECTION 4: Mediating Relationships

- Bibliography

- Index

- Copyright