![]()

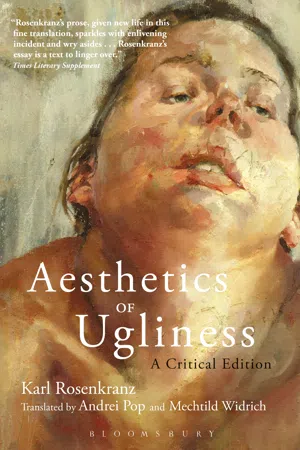

Aesthetics of Ugliness

Karl Rosenkranz

Translated by Andrei Pop and Mechtild Widrich

![]()

Foreword

An aesthetics of ugliness? And why not? Aesthetics has become the collective name for a large group of concepts, which is in turn divisible into three particular classes. The first has to do with the idea of beauty, the second with the notion of its production, that is to say, art, the third with the system of the arts, with the representation of the idea of beauty through art in a specific medium. We tend to gather concepts of the first class under the rubric of the metaphysics of beauty. But if the idea of beauty is to be considered, an investigation of ugliness is inseparable from it. The concept of ugliness, of negative beauty, thus is a part of aesthetics. There is no other science [iv] to which it could be assigned, and so it is right to speak of the aesthetics of ugliness. No one is amazed if biology also concerns itself with the concept of illness, ethics with that of evil, legal science with injustice, or theology with the concept of sin. To say the ‘theory of ugliness’ would fail to bring out so clearly the scientific genealogy of the word. As for the name, the handling of the subject itself will have to justify it.

I have taken pains to develop the concept of the ugly as the midpoint between that of the beautiful and that of the comical, from its first beginnings to the fullness it gives itself in the form of the satanic. In a way, I reveal the cosmos of ugliness from its first chaotic patches of fog, from shapelessness and asymmetry, to its most intensive formations in the endless multiplicity of disorganizations of beauty that is called caricature. Formlessness, incorrectness, and the deformity of disfiguration1 are the distinct levels of this self-consistent series of [v] metamorphoses. The attempt has been made to show how ugliness has its positive presupposition in beauty, which it distorts to create the mean2 instead of the sublime, the repulsive instead of the pleasant, and instead of the ideal, the caricature. All the arts and all the epochs of art among the most diverse peoples are hereby invoked to clarify the development of the concepts using apposite examples, which should also provide raw material and reference points for future students of this difficult province of aesthetics. Through this work, whose imperfections I believe I know best, I hope to fill a gap that has until now been all too tangible, for the concept of ugliness has until now been handled only in a fragmentary and incidental fashion, or else with great generality, which risks affixing the subject within very one-sided definitions.

The well-meaning reader who really seeks self-instruction may grant all this, and still ask: Should such an unpleasant, disgusting object be so thoroughly investigated? Undoubtedly, for science has in recent times touched on this problem again and again, and it requires [vi] resolution. Naturally I do not wish to advance a claim to having accomplished this. I am satisfied if here, as in other areas, it is granted that I have at least made a step forward. The individual may well think of this subject3:

—down there it’s terrible

And man should not challenge the gods

And desire never, but never, to behold

What they kindly conceal in night and horror!4

The individual may think thus and set aside the science of ugliness unread. Science itself, however, follows only its own necessity. It must go forward. Charles Fourier, under the rubric of the division of labour, defined one type that he called the travaux de dévouement [works of devotion], to which no one is predisposed by nature, but which men do out of resignation, because they recognize their necessity for the common good.5 The attempt to satisfy such a duty is made here as well.

But is this business really so terrifying in practice? Does it not also contain points of light? Does not a positive content also lie in hiding for the philosopher, for the artist? I certainly think so, for ugliness [vii] can only be grasped as the midpoint between beauty and the comical. The comical is impossible without an ingredient of ugliness, which it dissolves and re-forms in the freedom of beauty. This cheering and universal consequence of our investigation will excuse the undoubted pain of some sections.

In the course of the treatise, I excuse myself at one point, in a way, for thinking so much through examples. But it is obvious to me that I did not need to do so; for all aestheticians, among them Winckelmann, Lessing, Kant, Jean Paul, Hegel, Vischer, and even Schiller himself, who recommends the sparing use of examples, proceed in the same manner. Of the material that I have accumulated for this purpose over a span of years, incidentally, I have made use of only a little over a half, and may thus consider myself to have been quite parsimonious in this respect. Through my choice of examples I have only aimed to be many-sided, so as not to impose through examples a limitation on general validity which has plagued the history of every science.

[viii] The way I handle the material might seem old-fashioned and perhaps too precise. Modern writers have invented for themselves a striking method of citation, namely to sprinkle their texts liberally with inverted commas. Where they find the citation remains mysterious. It is a lot for them to add a name. But it seems to them pedantic to then add to the name of an author the name of a book. Doubtless it would be petty to always want to document generally known or irrelevant things with citations. But those points less common, less often touched upon, more remote, still debated, require, in my opinion, more precision of statement, so that the reader may, should it please him, go to the sources in person, and compare and judge for himself. Elegance can never be the goal of scientific discourse, only the means, and a very subordinate one at that; thoroughness and precision must stand above it.

With trepidation I see, after the printing, that among the examples quite a number have pressed forward out of the recent past, because they were freshest in my memory, [ix] because they occupy me with the same lively interest I take in their authors. Will these authors, among whom I count some friends, take this badly, will they regard me with bitterness? That would be quite painful for me. But the revered will have to ask themselves above all whether what I say is true. If it is, no wrong has been done to them. Then they will see from my mild way of complaining and in other places of praising, when it is earned, that my friendly disposition toward them has not changed. Yes, I even recall having made most of my censures first through letters. They cannot then wonder that I express the same opinion in print. I would leave out this entire observation, did I not know from experience how excitable modern minds are, how little disagreement they can tolerate, how much they wish to be eulogized and not lectured, how sharp they are, but only in critiquing others, and how especially and, above all from critics, they demand only sympathy and devotion, that is to say, admiration.

[x] I believe that my text is also readable to the general public, not just the educated. Only through the nature of the material does this accessibility have certain limits. I have had to touch on abominable things and call things by their true name. As a theoretician I have held myself back from the descent into certain sewers, and have contented myself with suggestion, as in the case of the Sotadic inventions.6 As a historian this course would not have been open to me; as a philosopher I was free to decide. And despite my extraordinary caution, some will judge that I need not have been so honest. But then, I may assure you, the investigation ought not to have been done at all, nor could it have been done. It is sad that for us a certain prudery creeps even into science, in that one makes discretion the only criterion for objects of animal nature and of art. And how does one best achieve discretion nowadays? One simply does not discuss certain phenomena. One decrees their non-existence. One secretes them away unscrupulously so as to remain socially acceptable. For example, one publishes [xi] woodcuts—for without woodcut illustrations modern scientificity is not really possible any longer—with microscopic detail in the service of a physiology, a doctrine of life, lectures held before a circle of ladies and gentlemen in a capital city, and one says not a single word about the generative apparatus and above all about sexual function. Certainly very discreet. Our German literature has already been castrated through this tidying up for girls’ boarding academies and finishing schools for noble daughters, all this to bring out for tender virgin and lady souls the beautiful, the sublime, the refreshing, the comfortable, the mellow, the edifying, and all the other catchphrases. An incredible counterfeiting of the history of literature has taken place, going beyond narrow pedagogical considerations to deface opinion; this counterfeiting is supported through extremely one-sided anthologizing of literary masterworks. What luck, that a work like that of Kurz should appear at this moment, which through its independence will force the [literary] factory workers at least once again to touch on other objects, in another sequence, with another judgement [xii] than those found in the ruts they have been treading ad nauseam.7 Every perceptive reader will understand that I, by all decency, could not write such a consumptive boarding-school style, and that in the present case I may apply Lessing’s words:

I do not write for little boys,

That go to school so full of pride,

Carrying the Ovid in their hands,

That their teachers don’t understand.8

Karl Rosenkranz, Königsberg, April 16, 1853

1 Verbildung meant broadly as negative figuration, not narrowly as destruction of faces.

2 Rosenkranz’s gemein is an everyday word with connotations of social status (gross, common, vulgar, coarse, base, vile) and ill will (petty, vicious, the modern use of ‘mean’). But it is also a technical term indicating a distortion of the sublime. Widrig likewise spans a range of phenomena of resistance, from the abstract (adverse or unfavourable: widrige Umstände, unfavourable conditions) to the visceral (repugnant, repellent).

3 The 1853 edition has Gestande, which is not a word. We follow the Reclam edition’s reading.

4 From the ballad, ‘Der Taucher’ [The Diver, 1797], by Friedrich Schiller, Gedichte (Stuttgart and Tübingen: Cotta, 1852), 304, with the full stop turned into an exclamation mark.

5 See Charles Fourier, Théorie de l’unité universelle, vol.4 (Paris: Société pour la propagation et la réalisation de la théorie de Fourier, 1841), 150, 161. Fourier thinks this a domain for child labour, especially those involving ‘répugnances industrielles’ (p. 138).

6 The word ‘inventions’ suggests that Rosenkranz is not referring to Sotades of Maronea, a Hellenistic poet writing lewd verse and comedy in Alexandria around 280 BCE (few fragments have survived), but rather...