![]()

SHIFTING GEOGRAPHIES

Susan Yelavich

There is an apocryphal tale about a beguiling garden city set amidst a borderland in Central Europe. Designed by Paul Heim, Hermann Wahlich, and Albert Kempter and built between 1919 and 1935, the town was called Zimpel. The story goes that the streets of this town were laid out in the shape of the heraldic German eagle, as would befit a suburb of Breslau, which was then a major city in Germany (Fig. 1). After World War II, when the Allies awarded an eastern swath of Germany to Poland, Breslau became Wroclaw, and neighboring Zimpel became Sępólno. Likewise, the eagle changed its feathers. Today, it is thought that the town plan cannot possibly refer to the German coat of arms because the Teutonic eagle’s feathers are always arranged parallel to its trunk, while the Silesian eagle’s feathers reach out laterally, as do the streets of Sępólno, at least in the eye of one beholder1 (Fig. 2). All by way of saying the town is Polish, not German.

This feather-splitting lore of regional identification is fascinating on at least two counts. In the first place, what seems to be a trivial claim based on local allegiances masks shifting geographies that entailed two ethnic cleansings: the Nazi’s expulsion of Poles and Jews from its eastern lands and the postwar expulsion of Germans from the very same region. Secondly, given that this is a twenty-first-century fabrication—there is absolutely no evidence to support it—we might also construe it to be a rehearsal of lingering resentments, hurts, and slights. A volatile mix of history and memory, the anecdote is not just a provincial phenomenon but part of pervasive pattern. Witness the series of crises in recent decades that have resulted from perceived and real threats to national, regional, and religious identities in the face of globalization.

A more hopeful response to the kind of folklore coming out of Sępólno comes from designers whose own lives and practices have been shaped by the mobility and multiple allegiances implied in this section’s title: Shifting Geographies. Instead of dismissing this tale of two eagles (and others like it) as a xenophobic fabulation, they see it as an opening for serious conversation. This section of Design as Future-Making is about those kinds of conversations, conducted through design practices of a different order and with different priorities. Instead of trying to invent fixes for social problems—be it in Sępólno or San Diego—designers are increasingly using their capacities to identify community initiatives that they can strengthen and amplify. Ezio Manzini, one of the most eloquent advocates of design as the co-production of social experiments, points out: “the planet is very rich with potential intelligent operators.”2 The scale of the social and environmental challenges that face us (and that designers now take into their remit) begs for the activation of that potential.

This is why growing numbers of architects, urbanists, and designers see their roles not as prescriptive but as catalytic. They run workshops, form NGOs, join city councils, and otherwise become involved in order to help create space (and sometimes spaces) for communities to exercise ideas about how they want to live. These are practitioners who give visibility and agency to those painted out of official narratives.

The impetus for such collaborations is especially clear in this excerpt from a call for entries to a project called Insiders: folklore coming:3 “The exercise of power, shrinking all the time under the influence of the constantly expanding processes of the capitalist economic system, leaves vacant spaces for those who wish to appropriate them…. [F]olklore allows people to connect with their past, with their collective history, what is at stake here is actually a central part of life in the present: something ultralocal at the heart of the global whole.”4

Recognizing the ultra-local at the heart of the global whole need not valorize only the parochial; it certainly doesn’t mean that there is no place at the table for the designer and her experience. In fact, it would be an abrogation of ethics for the designer to become so self-effacing as to be mute. Designers who worry that the inventiveness to be found in the everyday might be polluted by their interference might want to reconsider those interactions as cosmopolitan contamination—the constructive shifts in thought and action that come from engagement with others different from ourselves.5 After all, design is not a meditation; it is a conversation that, by definition, must be at least a two-sided exchange. Conducted in good faith, the conversation welcomes the unforeseen, a kind of experiment too often taken for granted. By extension, design is an experiment in giving presence to voices.

However, as the curators of Insiders note, “[this] will require the awakening of unfinished experiments that lie dormant in the folds of the present.”6 Future-making cannot be done in a historical vacuum. Therefore, it is worth remembering that many of those unfinished experiments can be located in early modernism’s flawed but sincere efforts to flatten the hierarchies that perpetuate inequity.

Sępólno was just such an experiment. It also happens to be a ten-minute walk from the Housing and Workplace Exhibition (Wohnung und Werkraumausstellung, or WuWA), organized in 1929 by the Deutsche Werkbund. Both estates were a product of the Weimar era’s pressing need for housing after World War I. Both embodied utopian ideals of socially progressive living. Sępólno provided attached and single housing, a school, and two churches (but no synagogue; this in a city that had the third largest Jewish population in Europe). Key, however, was the inclusion of small private front yards and nearby garden allotments, which are still worked today. These amenities provided a transitional space and activity for residents who may have found garden city urbanism unfamiliar and alienating.

WuWA did not offer gardens, but it did offer variations on the ideal of communal space. Some residences featured common entrances, communal dining and recreation rooms; many came equipped with built-in furniture, in keeping with the social economies of Existenzminimum.7 Most striking was the attempt to design housing typologies to suit the specific needs of different demographics, such as Hans Scharoun’s hostel for newlyweds and singles, Adolf Rading’s apartment block for families with children, and Paul Heim and Albert Kempter’s kindergarten, built not just for the benefit of young children but also to give mothers more time for their own pursuits. (While hardly feminist by today’s standards, the architects of WuWA consciously addressed ways in which their designs could free women from some of the drudgery of housework.)

However, where Sępólno was designed on the model of the English garden city, the WuWA estate was emphatically modernist. The young universal style was meant to transcend locality and, by extension, promote a pacific way of living untainted by nationalist allegiances and styles. (No matter that architects Heim and Kempter were involved in the design of both Sępólno and WuWA.)

That Sępólno and its street plan raise questions of identity today, and the WuWA estate does not, probably has more to do with the fact that the former still operates as a community, while the latter is unevenly occupied by disparate individuals and institutions. Still, it must be noted that the modernist architecture and spaces of WuWA have yet to trigger any open speculations about its German-ness. Regardless, the microcosm of “identitarianism” encapsulated in these two compromised utopias raises questions larger than their geography would suggest. Namely, can an architectural program, its internal massing, and its external appearance (its form-function) engender a social imaginary? Which begs the larger question, can design engender agency?

Today, as in the Weimar era, designers from all areas of practice (not just architecture) aspire to reduce isolation, whether the political isolation of the marginalized or the social isolation that permeates a culture of self-actualization via consumption. These designers are also aware that, for every obstacle they might remove toward the larger aim of affording agency beyond the typical confines of class, gender, or race, new issues will surface over time. More than being aware, they embrace the inevitability of shifting socio-cultural geographies and, to the extent possible, make room and rooms (virtual and analog) to account for the unforeseen.

Nonetheless, as architectural historian Antoine Picon has observed, there is a particular challenge for these alternative design practices because they espouse the same values promoted by twenty-first-century capitalism—creativity, emergence, and indeterminacy—using the same networked strategies, albeit toward different bottom lines.8 Perhaps one thing that global capital cannot afford, though, is a close attentiveness to, and recognition of, the truly specific conditions and variables that make up the ways people live and wish to live. This is where the intimacy of folklore may have an advantage.

Design projects like those discussed in this section of Design as Future-Making are not blueprints with minor variations, like those that fast-food companies use to adjust menus and décor to nationality and region. Working under a different set of pressures, designers committed to a social praxis have the liberty to work small. However, they also have the responsibility to explore when, where, and how that work can be extrapolated, reinterpreted, and shared. Designers need to be able to contend with shifting geographies and navigate the layered temporalities with tremendous humility.

![]()

URBAN ECOLOGIES: QUATRE SYSTÈMES DE CONCEPTION POUR LA FABRICATION DE “LA CITÉ”

William Morrish

Envelope of Regularity

Over the last ten years, an interdisciplinary team of earth scientists and researchers has been assembling a detailed global history of the interactions between humans and the rest of nature. The research team, comprising ecologists, natural historians, anthropologists, geographers, climate scientists, and environmental systems analysts, is using advanced digital tools and modeling techniques to organize an extraordinary volume of data on the 100,000-year-old relationship between human societies and earth systems. Mapping the historical, archeological, and paleo-environmental record has revealed that patterns of stability and collapse reverberate through the longue durée of human history. Thousands of observations and measurements of the earth’s biophysical processes—made over time, conducted from diverse geographical sites, and aggregated—make up the dimensions of a so-called predictable environment, an “envelope of regularities,” a relatively stable ecological and climatic space within which cities and civilizations have grown and prospered for millennia. But a century of dynamic, unprecedented change—population growth, rapid economic expansion, globalization, war, disease, climate change, mass migrations, and the rise of megacities—has thrown ecological rhythms and processes so wildly out of sync that we have moved into a wholly new envelope of regularity whose dimensions are historically different and still unfolding.

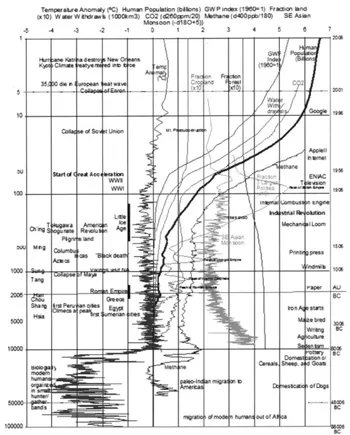

Fig. 1 Envelope of Regularity: selected indicators of environmental and human history. Lisa Graumlich, Robert Costanza, Will Steffen, Carole Crumley, John Dearing, Kathy Hibbrad, Rik Leemans, Charles Redman, David Schimil, 2007. Creative Commons License.

The lines in the middle of the diagram (Fig. 1), which sharply break out of the envelope of regularity, indicate massive environmental change on a global scale. We have entered a period of radical, successional redirection. Our urban theories and practices are based upon an ecological context that no longer exists. Simply tinkering with technology and markets, social systems, and urban form won’t do much to address how “the current global system will adapt and survive the accumulating, highly interconnected problems that it now faces.”1 Having crossed into this turbulent landscape of intense co-evolution, we need a new framework for thinking about city-building and living well within the unsettled environmental and social currents of our time, our inescapable, urbanizing ecologies. There is no going back.

This chart is composed of selected indicators of environmental and human history. While this depiction of past events is integrative and suggestive of major patterns and developments in the human-environment interaction, it plots only coincidence. In this graph, time is plotted on the vertical axis on a log scale running from 100,000 years before present (BP) until now. Technological events are listed on the right side and cultural, political events are listed on the left.

La Cité

Houses make a city, but citizens make la cité.2

—Andy Merrifield, “Citizens’ Agora”

I felt that Istanbul was my home, and Taksim Square my sitting room. And I felt that someone came in and bulldozed my sitting room.3

—Birkan Isim, a forty-year-old lawyer who blocked the first bulldozer approaching Taksim Square

Andy Merrifield’s reworking of Rousseau’s famous affirmation of citizenship translates la cité into a contemporary urban ideal, a new “citizens’ agora.” In ancient Greece, the agora was the heartbeat of the city, an open, highly valued public space that hosted civic assemblies, markets and libraries, schools and scholars, theater and discourse. A place of public action and imagination, an idea that encompassed a setting and the people gathered there, the agora supported a panoply of dialogues and encounters that sustained urban life. To be sure, the agora was hardly a perfect, wholly just civic space, but the ideal, expressed in urban form and the art of citizenship, created a lively, generative public realm.

Today, everywhere, the public realm is contested terrain. As cities increasingly rely on strategies of dispossession and enclosure to develop and brand the metropolis as a luxury product, the public realm, writes Merrifield, “hasn’t so much fallen from grace as gone into wholesale tailspin.”4 The demolition of informal markets and neighborhoods in Lagos and Rio de Janeiro, the rise of private eco-cities in Kenya and China, the tragic collapse of infrastructure and civil society in New Orleans in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, the economic gulf between central Paris and its poorest banlieues, and the appropriation of public space for private gain, as in Istanbul’s Taksim Square, all signal a politics of exclusion. These mechanisms segregate wealth and poverty, limit public dialogue, and enclose or control what should rightly be the commonwealth of all citizens: the cosmopolit...