![]()

1

Surface

Using enamel paint

George and Weedon Grossmith’s comic novel, The Diary of a Nobody (1892), explores the daily toil and trivialities of Charles Pooter, a City worker living in a suburban house called The Laurels in Holloway Road, North London, who is desperate to attain a position of middle-class respectability. The opening diary entries record Pooter’s bumbling encounters with tradesmen who are renovating the house he has just bought, but Pooter does not simply stand by and watch. Aspiring to greater self-sufficiency, Pooter contributes to these efforts of home improvement alongside his wife Carrie who ‘is not above putting a button on a shirt [or] mending a pillow’.1

In this wave of enthusiasm for home decoration, Pooter, on the recommendation of a neighbour, buys a couple of tins of red ‘Pinkford’s enamel paint’ and proceeds to cover a variety of household objects in a red layer, including flower-pots, the servant’s wash-stand, a chest of drawers, the spines of his Shakespeare plays, a coal scuttle and the family bath, much to the annoyance of his wife who laments this ‘new fangled craze’ (Figure 1.1). This infatuation with red enamel paint comes to a farcical end, however, when Pooter prepares a hot bath to alleviate a ‘painter’s colic’ that had developed while applying the substance. The heat of the water strips off the inexpertly applied layer of red enamel on to his body, giving him the appearance of a ‘second Marat’.2

As a form of surface intervention – the physical manipulation of the two-dimensional plane through the application of a surface layer – Pooter’s effort with Pinkford’s enamel seems particularly amateurish; his ill-fated foray epitomizes the dominant stereotype of amateur surface intervention as a misguided, mimetic act of decoration, personalization or ornamentation, reflecting a lack of technical capability and the superficiality of middlebrow taste. However, this tendency to critique, marginalize, ridicule or ignore amateur surface intervention on account of its poor quality or naivety has deflected attention from the significant modern cultural phenomenon that lies behind it: access to affordable, commercially produced tools and materials that allowed individuals, like Pooter, to engage in tasks previously undertaken by tradesmen or specialists.

This chapter accounts for the growth of this infrastructure of tools and materials that allowed individuals to add a layer on to objects after the initial process of commodity exchange, with a particular attention on the simplest forms of surface intervention: drawing and painting. The ‘things’ that facilitated intervention are the focus3: ready-mixed paint, pre-stretched canvases, brushes, paintboxes and manuals, produced commercially from the late eighteenth century onwards. As examples of new technology that invite the non-specialist to practise, these tools and materials ‘reconfigure the distribution of skill’, as stated by Elizabeth Shove et al. in The Design of Everyday Life – an important work that builds on Bruno Latour’s understanding that technologies and artefacts ‘script’ our engagement with them rather than being subservient to our will.4 Their twenty-first-century examples include self-levelling house paint that enables the amateur decorator to achieve a smooth, good surface finish. But within the longer history of tool access, the portable camera obscura that made it possible for eighteenth-century tourists to capture a scene, paint in tubes and the all-in-one 1950s paint-by-number kit can be added to this list of ‘smart’ tools. Competence and ability, enmeshed in the pre-modern era within the skilled labourer (and often protected through guild association) was re-distributed across a wider network from the late eighteenth century onwards, with the increasingly sophisticated tools, materials and literature incorporating complex tasks into their domain.

FIGURE 1.1 Pooter applying Pinkford’s enamel paint. Illustration by Weedon Grossmith. The Diary of a Nobody (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1965).

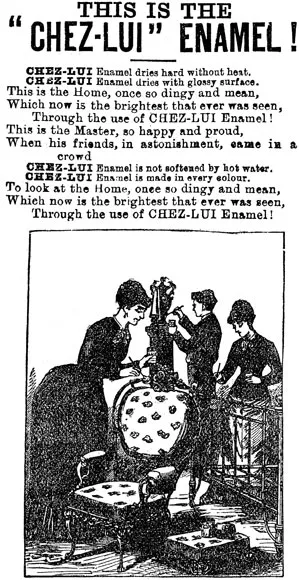

This brings us back to Pooter’s inglorious use of red enamel paint, which was not mere literary or comic embellishment but a direct reference to new brands of enamel paint developed from the mid-1880s that allowed non-specialists to cover surfaces – including baths – in self-drying enamel paint. Only a few years before the publication of Diary of a Nobody, weekly publications targeted at the diverse array of Victorian handymen, such as the Illustrated Carpenter and Builder (1877–1971) and Amateur Work (1881–96), ran advertisements for brands of enamel paint, such as Celestial Enamel, Aspinall’s Enamel and Prices’s Chez Lui Enamel (Figure 1.2).

Before the introduction of these brands, enamelling, and in particular enamelling baths, typically involved a series of complex tasks – it was ‘a highly skilled job’ according to paint historian Harriet Standeven.5 For a start, the enamel paint needed to be mixed in the right quantities from a combination of strained white paint, varnish, and enamel varnish; several coats were needed to prepare for the final glossy surface; the material had to be ‘flowed on’ to the surface quickly in one continuous movement without leaving gaps, as the work could not be touched up; and, if greater durability were required, baths would have to be sent to specialists for stoving, where the surface layer would be fired on in large kilns.6

New enamel paints decentralized this process into the home. Chez Lui enamel, as the editor of Amateur Work noted, resembled paint in both appearance and its behaviour when being applied, the material changing only during the process of drying: ‘[Chez Lui] will present a surface almost as smooth and as glossy as porcelain, while that of ordinary paint, even at its best is somewhat rough to touch.’7 It was these self-levelling qualities of the new technology – that it dried to a smooth finish – that were so valued, particularly in the contexts of increasing concern about sanitation and cleanliness.8 Readers of Illustrated Carpenter and Builder recommended both Chez Lui and Aspinall’s enamel as they were easy to use, could resist both hot and cold water when dry, had a wide colour range and could be used on a variety of surfaces – including wood, stone, glass and metal.9 Moreover, the process was so straightforward that instructions guiding the enameller on the side of the paint-tin sufficed as adequate instruction, anticipating the famous tagline of the British stains and paint manufacturer Ronseal: ‘It does exactly what it says on the tin.’10

The availability of readymade enamel paints in the late 1880s provoked responses that often accompany the democratization of any skill. Skilled labourers and commentators alike were happy to poke fun and identify the faults and mistakes associated with non-specialist practice.11 Indeed, the domestic use of Aspinall’s Enamel was the subject of an 1896 song written by W. M. Mayne for the well-known and well-travelled caricaturist, entertainer and Yorkshireman, Mel B. Spurr.12 The first verse reads:

When a woman enlists under Aspinall’s banner

She ought to be kept in restraint in some manner.

Just give her unlimited scope, and full powers,

And she’ll alter the Town in a very few hours.

St Paul’s would be painted Emerald Green:

The Houses of Parliament Ultramarine,

FIGURE 1.2 Chez Lui enamel advert. Illustrated Carpenter and Builder 22 (17 February 1888), p. 142. Courtesy of Bodleian Libraries.

And Westminster Abbey a sealing-wax Red,

With a sweet peacock Blue for the tombs of the dead.

And I don’t think a woman is right in her head

Who would put peacock Blue on the tombs of the dead.13

Pooter’s misapplication of red enamel paint, and the ardour of the housewife armed with Aspinall’s enamel are two pejorative characterizations of amateur surface intervention that are often feminized (see Figure 1.2). The amateur is portrayed as lacking knowledge about how tools and materials work, with a will to beautify without skilful execution, and an inability to regulate labour power, as is the case with the obsessive enameller described in Mayne’s lyrics.

Throughout the book I want to move beyond this rhetorical marginalization (and feminization) of amateur craft practice, and in this chapter I do so by focusing on the things that decentralized surface intervention (classified below as bases, carriers and arbiters). In the hands of amateurs, new tools and materials enabled individuals to express personal taste and creative autonomy, but they equally set the parameters of what could be achieved and the type of practice that unfolded. The amateur surface intervener was not suddenly able to do anything he or she so desired. Competence was distributed between the maker and the tool, as Shove et al. have stated.14 Their argument supports the claim that amateur surface intervention is not merely a subjective act of expression but an appropriative and dependent act: the ability of an individual to harness an entire network of production.

To prioritize the importance of the amateur’s interaction with tooling is one goal for this chapter. But the second key hypothesis is that the advent of tool and material accessibility thrust the issue of distributed competence and appropriation into the realm of artistic production. As explored below, the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century ushered in a period of chemical and technological progress that fuelled the commercial provision of artistic supplies, which removed the need for artists to engage in the tasks that previously preceded the production of a painting, such as stretching canvases or grinding colours. As the French artist Marcel Duchamp stated in a series of interviews in the 1960s – all art was readymade from this moment on, when equipment and supplies, like paint in tubes, were industrially produced.15 But rather than seeing this as evidence of de-skilling within art, the end of the craft of painting, and the beginning of the conceptual age, as many do,16 I build on recent theory to suggest that skill was simply re-configured and did not disappear. Artist and amateur alike were faced with readymade abundance, but this did not lead to a clear meeting point between the amateur on the ‘way up’ and the professional artist on the ‘way down’, ‘under the auspices of deskilling’, as claimed by the theorist John Roberts.17 Although amateurs and artists might go through similar processes of choosing and applying surfaces, they move in different directions, with different intentions and goals for their work.

Let us return to enamel paints to demonstrate this.

A couple of decades after the popularization of Aspinall’s and Chez Lui, Duchamp was also messing about with enamel paint. His 1916–17 assisted readymade Apolinère Enameled, uses as its base a tin-plate advertisement that is remarkably similar in composition to the Chez Lui advertisement (Figure 1.3). Duchamp manipulated the readymade into a misspelt, humorous message to his poet friend Guillaume Apollinaire: he carefully erased the ‘S’ of Sapolin – an enamel paint product – and added ‘ère’ and ‘ed’ in white paint.18

We could situate Duchamp’s playful surface intervention within the art historical narrative of art’s increasing distance from representation; art used not to depict something, but to reference the relationships and mechanisms within the artworld: Apollinaire was an influential critic besides being Duchamp’s friend. We could frame it as a surface intervention with an ‘internalized’, philosophical, aesthetic and political language, what Thierry de Duve termed ‘a reprieve’, ‘an avant-garde strategy devised by artists who were aware that they could no longer compete technically or economically with industry’.19 Surface interventions as diverse as the Impressionist foregrounding...