![]()

1 DEFINING

What do professionals do all day? How we answer this question has implications for what they need to know, how this can be learned and consequently the provision made for their initial and continuing education (Zeichner et al., 2015). While the nature of professionalism is contested and subject to change, the capacity to make judgements about what to do in complex, uncertain situations and the assumption of collective responsibility are the moral and practical basis. Professionals, therefore, have a dual responsibility for their own ongoing learning as well as for the induction and development of others within the profession. The added jeopardy of professionals in education is the fact that their professional learning is for the majority inextricably linked to the learning of their students. In this book we explore what professionals know and how they learn. The perspectives and tools we share can be used to gain insight into professional learning and will be of value to researchers, policymakers and practitioners with an interest in improving professional education.

Thinking through practice

It is critical to acknowledge that professionals engage in practice; indeed, many adopt the identity of practitioners. It is perhaps this relationship with practice and practical contexts that leads to definitions of what it means to be a professional and which occupations can claim the status of being a profession changing over time. It is also what makes some traditional approaches to research challenging to apply. Practice is complex and messy; therefore, any associated enquiry needs to either attempt to assert control, which arguably leads to criticisms around the creation of artificial simplicity (a lack of connectedness to real life), or ‘embrace the chaos’ leading to claims of bias, lack of rigour and difficulty in generalising claims. However, this all depends on what we believe practice to be.

Lampert (2010) outlines four typical conceptions of practice, all connected by its focus on what people ‘do’. She outlines how it

1 is contrasted with theory,

2 is used to describe a collection of habitual or routine actions,

3 as a verb speaks to the discipline of working on something to improve future performance, and

4 is in global terms used as a short-hand to indicate the way that professionals conduct themselves in their role.

To understand practice then we have to address the contrast with theory by exploring conceptions of practice through concepts offered by number of theorists. However, this is not ‘the theory part’ of the book, divorced from the goal of finding useful ways to describe, improve and identify what practitioners and professionals do in a grounded illustration. We have chosen therefore to use extracts from an example of practitioner enquiry (Lofthouse, 2015) in which a conscious attempt to bring theory and practice alongside one another leads not necessarily to tidy resolution but rather a picture of the difficulties and dissonance. In this way we will, without delving too deeply into Aristotle, be directing attention to the working together of theory (episteme) and products (poesis) in the crucible of practice or phronesis which is sometimes translated as practical wisdom wisely used in context, ‘the ability to see the right thing to do in the circumstances’ (Thomas, 2011, p. 23).

It seems important to ask: What are the circumstances? Contemporary views of practice and professionalism are not rosy: Sachs (2001), for example, contrasts managerial professionalism with democratic professionalism. The former prioritises accountability and thus encourages efficiency and compliance, while the latter promotes teachers as agents of change. Democratic professionalism creates opportunities for more nuanced development of practices, with the implication that in that democratic space both ‘reflection in action’ and ‘reflection on action’ (Schön, 1987) can and will take place.

The rise of managerialism, however, is arguably in response to the ‘normal chaos’ of modernity (Lash, 2003), in which the choices and risks of each individual as part of a pattern of interactions which shapes all our lives, through a globalised economy, a dissociated state and new configurations of family and community. Lash argues, ‘This choice must be fast, we must – as in a reflex – make quick decisions’ (2003, p. 51, original emphasis):

Thus certain aspects of practice and research feature strongly … because of my working relationship with my professional and academic role and the policies that influence it. At times I have been less reflective or deliberative in my actions than I would choose to be because measured judgements have been replaced by reflexes, and this has led not to certainty in the knowledge I have created but to what Lash describes as precarious knowledge. I state below my ontology and epistemology as part of my self-narrative, which as Sachs proposes relates to my ‘social, political and professional agendas’ (2001, p. 159) and which have created, through reflexivity, iteration and reciprocity of practice and research, my professional identity. (Lofthouse, 2015, p. 14)

Thus, when we engage with Schön’s (1987, 1991) description of reflexive practice, this is arguably a counsel of perfection. The chaos and structural constraints of practice suggest that for ‘in action’ reflection, practitioners are unlikely to be able to habitually perform this at the speed required. Reflection ‘on action’ can lead to a shift of attention in practice however, creating slightly longer ‘moments of opportunity’.

There is another important critique from Eraut (1994), who focuses on skilled behaviour and deliberative processes in ‘hot action’ situations to unravel the dilemma of practice that characterises the competition between efficiency and transformative quality in professional life. Eraut argues that these skills and deliberations are resting upon but also sometimes muffled by routines and taken-for-granted aspects of context, with the result that the idealised reflexive practice seems further out of reach.

There is help from an unlikely pairing to make this both more concrete and more hopeful of finding the ‘democratic space’. We need a frame for understanding (to borrow from Richard Scarry) – what people do all day. In his beloved, richly illustrated children’s books, Scarry invited readers to consider the activities engaged in by different (but all ‘busy’) people and proposed simple comparisons (inside/outside) and points of debate (hard?/easy?) that are arguably the bedrock of the philosophical inquiry we undertake here. We want to think about what it is that practitioners are up to all day, why they concentrate their busy-ness on particular activities and how much agency and intent are involved in that balance of concentration.

Arendt’s typology of ‘labour’, ‘work’ and ‘action’ serves to illuminate the realities of the classroom. Arendt distinguishes in a clear hierarchy between labour, which serves an immediate and life-sustaining purpose but leaves no lasting trace of itself (e.g. cooking, washing up, laundry), work, which produces lasting artefacts that shape how we live in the world (e.g. a table that we then sit around to eat), and action, which gives meaning to the individual within the society (e.g. singular, unusual, theatrical and problematic deeds that do not fit a pattern and provoke ‘histories and essays … conversations and arguments’) (Higgins, 2010, p. 285). It is worth emphasising that the majority of human activity is labour and work, while action – almost by definition – happens rarely. As practitioners, we can instinctively judge for ourselves which aspects of the day are labour and work and which might have the potential for action.

Arendt’s position is a strong riposte to managerialism and its normative discourse of standardised best practice, since what counts as work and action has both objective and self-determined aspects: the table is there, the people around it are arguing, I made both of those things happen. Unfortunately for this chapter and our argument, Arendt didn’t think education practitioners had much capacity for action as they were too highly constrained by the routines and structures of the system. We would, returning to Eraut, suggest that everyone is to a certain extent constrained in this way and that awareness of the constraints might be a way to move from moaning about them to deliberative practice and learning from/through experience (Ericsson et al., 1993).

There is a remaining problem for us with Arendt’s framing: the motivation appears to be highly moral and individualistic, whereas our understanding is rooted more in ideas of participation in communities of practice (Lampert, 2010) with strong ties to our colleagues and students, so we find the transactional and democratic ethics of Dewey (1916; Baumfield, 2016) to be helpful in explaining why certain problems draw education practitioners’ attention, driven by immediacy and the practical problems of the learning community. Practitioners are by very nature of their practice problem-solvers, with Dewey reminding us that experience is experimental inquiry: he challenges the idealist representation of experience as confined by its particularity and contingency through a recognition of our purposeful encounter with the world and the goal of learning.

Lofthouse (2015) suggests that the process of practitioner enquiry is a key component of reflecting on and improving practice: practitioners actively asking questions of their practice and using the process of engaging in and with (Cordingley, 2015a and b; Hall, 2009) research as a ‘pragmatic, but scholarly approach’ (Lofthouse, 2015, p. 12). She offers three ethical principles on which practitioner enquiry should facilitate:

Firstly I have an allegiance with my successive cohorts of learners. Secondly I believe that my practice can always be improved and that reflection on my own practice is the focus for improvement, and I promote reflection on practice for my cohorts of learners. Finally I recognise the strategic priorities of the institutions for which I work, which in effect are both the university, the schools and colleges in which my students and research participants practice, as well as the institution of education more generally. Thus I believe that my episodes of practitioner research are grounded in the ethics of the improvability of practice, the desire to meet the needs of the professional communities, and my deep understanding of the demands and cultures of their workplaces. (Lofthouse, 2015, p. 12)

If that is what practice can be, we must not avoid discussion of what it is for: Billet (2011) describes practice-based learning as having three broad purposes. In professional contexts it should enable leaners to develop an informed desire to enter the profession (or not) and ensure that they have the opportunity to demonstrate the necessary capacities required for entry, while also facilitating the development of occupational competencies for future professional learning. Billet also articulates the significance of three dimensions of practice-based learning. These are the practice curriculum (how the learning experiences are organised), the practice pedagogies (how the learning experiences are augmented) and the personal epistemologies of the participants (the means by which the individuals come to engage). Again, we want to nest this within the understanding of managerial and democratic professionalism. Performative cultures such as those experienced across many publically funded services (Ball, 2003) may open up limited spaces for democratic professionalism, instead heightening the role of managers to direct and validate the work of those they manage, leaving less room for professional discretion and perhaps creating an argument for training rather than learning. Managerial professionalism relies on routines and procedures.

What is practitioner enquiry?

In 1904, Dewey first discussed the importance of teachers engaging in pedagogic enquiry to fully engage with processes and outcomes in their classrooms. Since then the concept has been in and out of fashion and more or less tied up with the concept of the research-engaged practitioner. Underpinning these debates has often been an assumption that practitioner enquiry will lead to an engagement with research as a means to generate answers to pertinent questions of practice (Nias and Groundwater-Smith, 1988). This could be research-informed and/or involve research processes on the part of the practitioner (Cordingley, 2015b; Hall, 2009). For many this position naturally involves the participation of university academics to facilitate this engagement (Baumfield and Butterworth, 2007; McLaughlin and Black-Hawkins, 2004), and Timpereley (2008) states an important role for the expert (although not necessarily university based) in facilitating professional learning and providing critical support.

The current models of teacher-practitioner research can be largely traced back to the work of Stenhouse (1983), and as a result, over recent years, there has been more or less sustained interest in the process and impact of developing a research-engaged teaching profession. Completing a systematic review on the topic, Dagenais et al. (2012) found that practitioners with an inquiry standpoint were more likely to have positive views of research and therefore were more likely to use it to inform their practice. However, this link with research as a given of practitioner enquiry is a significant turn-off for some, and so how we manage this aspect of practitioner enquiry as professional learning is an important issue. There is something significant about the way that experts, whether colleagues in school, in local authorities, in specialist organisations or in universities, portray the accessibility and manageability of research in relation to everyday practice.

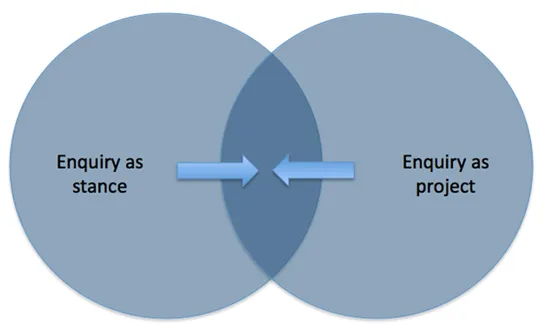

There are two dominant standpoints on practitioner enquiry with a potential lack of transfer between the two. On the one hand we have the likes of Cochran-Smith and Lytle (2009) who suggest practitioner enquiry is an epistemological stance, a way of understanding the world and how it is made up – a way of being that is tied up with views of democratic purpose and social justice. As such it is about giving informed voice to teachers in such a way that supports them in improving outcomes for students. By engaging teachers in better understanding the teaching and learning interplay in their context, and enacting and evaluating change as part of communities of practice, then practice will be improved (Baumfield et al., 2012). This process of engagement is likely to involve a research process, but it is primarily about questioning and looking for answers as part of a general professional commitment to keeping up to date with new developments.

On the other hand, we have a standpoint much more directly associated with research. Menter et al. (2011) defined enquiry as a strategic finding out, a shared process of investigation that can be explained or defended. This can often manifest as a more project-based approach to practitioner enquiry and as such could be perceived as more doable in its increased tangibility. One of the challenges here, though, is that the popular language of research is dominated by evaluation and as such a scientific understanding of process. As such, it is tied up with conceptions of expertise and academia and can seem a long way off from the remit of a practitioner in regards to knowledge and skill. It can often be seen as something that is finite and therefore not cumulative as would connect more easily to career-long professional learning (Reeves and Drew, 2013). This increases the likelihood of an individual feeling like they have done practitioner enquiry once a piece of research or a project has been completed. For this approach to work then a more practice-friendly understanding of research has to be promoted (see Figure 1.1).

FIGURE 1.1 Bringing the two predominant practitioner enquiry stances together.

The two standpoints are not and should not be put in opposition. That is not the intention here. Rather it should be a meeting of two minds as for the experienced practitioner-enquirer they merge forming a dynamic interaction between a desire to question practice and a systematic approach to finding out the answers. It becomes a synergetic process of engagement in and with research (Cordingley, 2013; Hall, 2009) that sustains and informs a world view where the practitioner has agency (individually ...