![]()

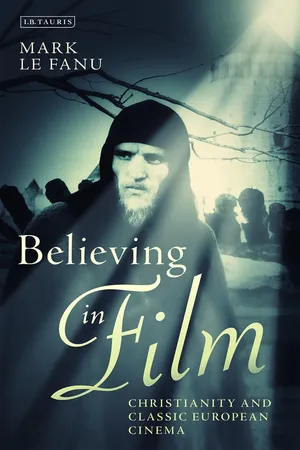

FIGURE 1 A modern Christian epic: Tarkovsky’s Andrei Roublev.

1

Russia: Tarkovsky,

Eisenstein and Christianity

The epic quality of cinema spectacle has been a defining aspect of its identity since the experiments of Griffith and the Italians in the early teens of the twentieth century. Like everything else in art, the genre finds itself, every so often, in need of renewal. Perhaps no modern example of this renovating imperative in epic made a greater impact than Tarkovsky’s Andrei Roublev, shot during the period 1965–6 but only released in Russia in 1971 after bitter spats with the Soviet authorities. The ostensible concern of the censors was with the film’s explicit violence and sexuality, but the secret (yet in retrospect obvious) reason for official displeasure can more plausibly be traced to the fact of its contours being unmistakably Christian. Christian in subject matter of course – the movie deals with the life of the monk/icon-painter Roublev as he travels round Russia in the early years of the fifteenth century – but Christian also, more importantly, in sympathy and allegiance.

I am assuming here that it was the latter aspect that really caused all the trouble, for after all it is theoretically possible to tell such a tale in a manner that subordinates the historical and contingent practices of religious belief to the supposedly deeper truth of dialectical materialism. There is indeed a lot of ‘talk’ in Andrei Roublev – too much for some people – yet insofar as the viewer manages to decipher the sometimes obscure and rambling dialogues that take place at intervals in the action between Andrei and his priest-companions, rather little of it is subsumable to the categories of orthodox Marxism. On the contrary, both the language and the spirit are theological. Shocking in the Soviet Union, where atheism had been inscribed as official state ideology for nigh on half-a-century, this state of affairs was perhaps no less shocking to filmgoers in the West, where (following a bungled attempt at repression by the Soviet film agency Gosfilmofond) the film was released in 1969 and received wide contemporary exposure. The shock, if one can call it that, may be described in two ways. It was an aesthetic shock first of all; the film’s extraordinary energy and formal inventiveness made a deep impression on everyone who saw it. But beyond this first level of technical grandeur lay a deeper wonder for people inclined to think about such things, which was: how on earth, in a country like the Soviet Union, did the filmmakers think they could get away with it?

In the years that have unfolded since the movie’s release, a number of studies have delved into the cultural background of Tarkovsky and his co-scenarist Konchalovsky (the latter still alive as I write, a frequent and articulate visitor to the West). Conferences, documentaries and informal cultural exchanges across borders in the decades since the collapse of communism have allowed researchers to investigate the private beliefs of intellectuals and artists in the Soviet period in some detail, and to document soundly what had merely once been an intuition, namely that the proscription placed by the State on religious observance never succeeded in banishing the habit of thought about religion from ordinary cultural life at all levels.

Tarkovsky and Konchalovsky belonged to the generation of Soviet (or, as I would prefer to call them, Russian) filmmakers who came to maturity at the time of Khrushchev’s ‘thaw’, and it is clear that other filmmakers besides them benefited from the relative intellectual freedom of the time to write and direct movies that challenged materialist ideology. The Georgian-born Armenian director Sergei Parajanov (1924–90) springs to mind as an obvious example to place beside Tarkovsky and Konchalovsky, though in his case there were indeed repercussions in the legal sphere; his outspokenness led to periods of imprisonment. Such films by Parajanov as Shadows of Our Forgotten Ancestors (1964) (made in Ukraine) and The Colour of Pomegranates (1968) are among the most beautiful works of art of this period, in any medium. Each of them, though very different in form and content, has immense spiritual power, as well as being visually and musically gorgeous. Their outspokenness lay not so much in any direct call to religious belief – religion, as such, plays little part in the narrative development of Shadows of Our Forgotten Ancestors – as in the unmistakable feeling communicated to viewers of the irrelevance of atheistic communism in defining the values and traditions that the movies are interested in honouring. Religion is ‘invisibly’ there, so to speak, built into their texture, beauty and historical accuracy – even into the way the characters talk to each other.

FIGURE 2 ‘Among the most beautiful works of art of this period, in any medium’. Sergei Parajanov’s The Colour of Pomegranates (1968).

Now it is true that a lofty and pious humanism had always been part – perhaps indeed a defining part – of a certain strand of Soviet filmmaking (I am thinking of a director like Tarkovsky’s friend Vassily Shukshin, but also others I like such as Khutsiev, Klimov, Panfilov and even Mikhalkov); yet these films by Parajanov pushed the issue a crucial step further in the direction of saying, or implying, ‘No, there is nothing wrong with religion after all.’ In fact he was not alone in this endeavour. A comparable, though differently expressed, boldness may be found in certain other directors of the time; Larissa Shepitko, for example, whose brief career, cut short by a fatal motor accident, occupies a significant landmark in late Soviet filmmaking. Thus, while the Western filmgoer was free (eventually) to admire the audacity, in the pre-Gorbachev era, of a movie like Andrei Roublev, he or she could also see and wonder about a movie like Shepitko’s The Ascent, released in the following decade, though still many years before the collapse of the system.

FIGURE 3 ‘Finding […] the moral strength to face what is going to happen to him’. Boris Plotnikov as the Christ-like partisan Sotnikov in Larissa Shepitko’s The Ascent (1977).

Adapted from a novel by Vassily Bykov, the film, which came out in 1977, follows the inner spiritual journey of two contrasted partisans, Sotnikov and Rybak, seeking to evade capture in Nazi-occupied western Russia during the war. Rybak seems much the stronger, both physically and mentally, of the two, and indeed constantly gives his companion succour; but when they are finally captured it is Sotnikov, the weakling, who shows truest fortitude in the face of the trials that await them. For fate has delivered them into the hands of a truly terrifying adversary, a nihilistic Russian interrogator in the pay of the Nazis, played with Dostoevskian brilliance by one of Tarkovsky’s favourite actors, Anatoly Solonitsyn. With deft and subtle precision the film mines the complexities of conscience. The weak man, Sotnikov, finds the strength to face whatever it is that is going to happen to him, up to and including the inevitable end: a grisly death by hanging, which we witness. By contrast, Rybak’s initially admirable life force (he at any event will do anything to escape his captors, in order to carry on the anti-Nazi struggle) is shown at a certain crucial moment to become corrupted into its opposite: a craven fear of personal extinction that allows him to bargain with the enemy and to betray the trust of his comrade in adversity. The important point to make, for criticism, is not, here, that the film is explicitly ‘Christian’ – though in a sense that is true; the interrogator is the devil, Rybak is Judas, the scenes leading up to the execution, along with the title of the film itself, make plain reference to the Christian Passion – but that its moral vocabulary, transcending Kantian humanism, belongs in the deepest sense to the traditions of world religion. The film is not able to be understood unless such concepts as sin, redemption and witness – notions that also belong to Judaism, of course, and to other religions – are allowed to be still-living categories.

Tarkovsky’s later films take up this notion of sacrifice. A believer himself on a personal basis (as his diaries, full of plangent invocations to the Almighty, make abundantly clear), he was plainly, I would think, during his tragically short life, the most important modern Christian filmmaker. More than almost any other contemporary film artist, he tells us what he thinks without coquetry; he is absolutely not a postmodernist. Yet his Christianity is not without mystery; it is sometimes hard to say exactly and precisely how he is a Christian. His autobiographical film The Mirror (1974) manages to avoid the topic, or else broaches it only obliquely, through cultural reference to previous Christian artists (Leonardo, Pushkin, Bach etc.) None of the main characters is specifically glimpsed at prayer, though an iconography of hands (above all, hands held up so that light glimmers through them) forms an important visual motif of the movie. Stalker (1979), meanwhile, his next film (and the last that he made in Russia), is underpinned by an idea that is more psychoanalytical than religious: that we must be careful about the purity of our wishes (or else they will come back and bite us). This puzzling maxim is in any case borrowed from Roadside Picnic, the tale by the Strugatsky brothers upon which the movie is based, and is not necessarily one that Tarkovsky swore by. Nonetheless, there is a ‘sort of’ detectable Christian undercurrent to the film, connected to humility and sacrifice and patience, qualities that are also at the heart of Nostalghia (1983), this time with a more recognisable Christian iconography of candles, churches and grandly beautiful images of the Madonna.

And yet Nostalghia is detectably pagan too! At least, the scenes set in Rome strike me as being so. The whole subplot concerning the self-immolation of the protagonist’s friend Domenico (Erland Josephson), who sets himself alight in the Campidoglio after mounting the back of the equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius, is intractable to Christian interpretation; it belongs, as imagery, to some other worldview – the Viking pyre, perhaps, or the grim godless lessons of the auto-da-fé.

FIGURE 4 An unintended flavour of paganism? Domenico (Erland Josephson) in Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia (1983).

If light is ‘obviously’ religious, fire, as a symbol, can be, depending on context, both Christian and not Christian. At any event, it is difficult not to see that Tarkovsky is in love with its properties. He makes it the climax to the last film he ever made, Sacrifice (1986), set in Sweden, in which, in response to a private vow made to God (who has allowed him to survive the night and to save the world from nuclear destruction), the protagonist Alexander makes a bonfire of his house and possessions before surrendering his person to a hastily summoned ambulance crew. He leaves behind a six-year-old son, and this child tends a little tree he has planted beside the ocean.

So we are left with a feeling of redemption, though the imagery is not transparently that of the Christian story. Still, it is not not Christian either! That is how difficult Tarkovsky is. He ‘speaks out’, but he also hides things. He hates symbolism, but he is a symbolist. If we are looking for the simplicity of an ‘edifying parable’, we will most likely have to search elsewhere.

*

Let’s return at this point to Russia, and to history. With its victory in 1917, and then again in 1921, Bolshevism launched an all-out attack on the past. The intention was to replace traditional religious faith with the newly forged religion of humanity. The godless New Man and New Woman are the subject matter, at bottom, of all art in the Soviet period, though of course how the phenomenon manifested itself differed widely from artist to artist and from decade to decade. The tone at the outset was brashly militant; a certain atheistic dogmatism and truculence seems to be, in retrospect, an inescapable ingredient of the work of the great silent masters, Eisenstein, Dovzhenko, Pudovkin and Dziga Vertov (to take only the four most famous of them). Modern commentary on these filmmakers tends to distance itself from the necessity of taking a position, one way or another, regarding the truth or lack of truth of their ideological parti pris, concentrating instead on expounding the formal and aesthetic quality of the art in question. After all (the argument goes), the directors themselves were ‘formalists’ and when, at the end of the twenties, formalism came under Stalinist interdict they paid a heavy penalty for their predilections. What, anyway, does ideological truth, or for that matter ideological error, mean today, judged by the verdict of history? In our postmodern world, the very word truth is unable to be deployed without the visible or implied support of scare quotes. Nevertheless, the modern reader/viewer can still feel frustrated by a certain lack of candour and even of common sense in discussing the issue. Can there be (one asks oneself) any value in extensive exegesis of a given director’s films if the very impulse that guided his or her vision at the outset is never to be openly spoken about? And a further untimely thought insinuates itself: is it actually so necessary that we like all these directors?

Among the filmmakers just mentioned I won’t attempt to disguise the fact that I have never very much admired Dziga Vertov. His most famous film, Man with a Movie Camera (1929), will, of course, continue to find an honourable place in all histories of documentary cinema. Undeniably the syncretic picture of the Russian city at the end of the 1920s given in the film has extraordinary historical and sociological interest. Placing his camera on every imaginable crag and vantage point (the photographer was Vertov’s brother Mikhail Kaufman), and editing together the resultant footage dynamically, that is, with a sure sense of rhythm and tempo, Vertov constructs an avant-garde artefact – a formalist tone poem – that may still be viewed today with enjoyment. Yet it seems to me that such enjoyment as we gain occurs in the parts where what we are being offered is, relatively speaking, an ideological holiday. In Man with a Movie Camera there are scenes of play and pleasure – there is even a nice extended party sequence with a horse-drawn carriage – which alleviate the otherwise relentless insistence the film maintains on the coming of the new Soviet epoch.

What ‘Soviet construction’ really amounts to in the heart of a man like Vertov can be more clearly seen in a contiguous film directed by him, The Eleventh Year (1928), a would-be heroic account of the transformation of the countryside of the Donbass region in the Ukraine in order to set up a huge hydroelectricity project. The envisaged power will come from two sources: water – for which reason a dam is to be constructed, immersing many surrounding acres – and coal, necessitating a massive mining operation which, no less than the projected dam, will leave savage scars on the face of the landscape. The glee with which Vertov records the disruption of nature has to be experienced to be believed; it takes the ideal of anti-sentimentality in Soviet art to new levels. Colossal explosions, artfully photographed, shatter traditional orchards and meadows, and somehow one knows there is no regret here. Early on in the film, excavating engineers uncover the bones of a 2,000-year-old ‘Scythian’ skeleton. Most professional people would feel a certain compunction about disturbing the ancient dead. At least one could imagine they would pause for a moment and think back over history, even entertain a few thoughts on the passing of time and the transience of human endeavour. This is not Vertov’s way; any unearthed skeletons are taken to be ancestors of communism. Rather than say go away, they will hearken to the sound of the pickaxe! One searches round for comparisons to ‘place’ such impiety. At much the same time as Vertov was filming The Eleventh Year, Platonov in far-away Voronezh was completing his extraordinary novel The Foundation Pit, in which the construction of a vast, bottomless hole in the ground is dramatised as the way forward for Soviet civilisation.

In Platonov, of course, the intention is satirical; his characters mouth the clichés of socialism, but they, and the place, and the language they use, are all, in truth, literally godforsaken. This forlorn ‘lack of God’, more than any other factor, is the measure of contemporary deformation; it is what makes Platonov’s writing (for all its human kindness) so genuinely creepy and sinister. By contrast, The Eleventh Year produces a similar effect of melancholy, but absolutely unintentionally. In place of Platonov’s literary tenderness, we find in Vertov a strident and humourless positivism. No image in Vertov’s film is more resonant, perhaps, than the sight the director grants us of the Triumph of Mining; a bare-footed woman, pickaxe raised, has leapt onto the mine’s conveyor belt, from which vantage point she is smashing shards of coal into smaller and smaller fragments. On either side of the moving mechanism, a bevy of female co-workers sift the results of their comrade’s fantastical and terrifying labours. A bristling feeling in the back of one’s neck accompanies the reflection; this is what Vertov thinks civilisation is.

*

One might expect there to be like moments in the movies of Eisenstein, who, like Vertov (at least in his early professional life), had similarly bought into Bolshevism’s all-encompassing vision of the future. There is no sentimentality in the way that Eisenstein treats the old monarchical system, and the religious ideology that supported it, in a movie like October (1927). In a famous sequence from that film, following the storming of the Winter Palace and the invasion of the tsar and tsarina’s living quarters by an angry mob of sailors, private devotional statuettes of the Redeemer and the Virgin Mary owned by the pair are juxtaposed, by deft editing procedures, with images of grotesque Eastern idols and indolent recumbent Buddhas; undifferentiated tokens, all of them, of superstitious benightedness. The satirical intention is unambiguous. Eisenstein, at that stage, was no friend of the ancien régime – and no friend of religion. So indeed it might have continued; subsequent years brought the director into conflict with the demand...