This is a test

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

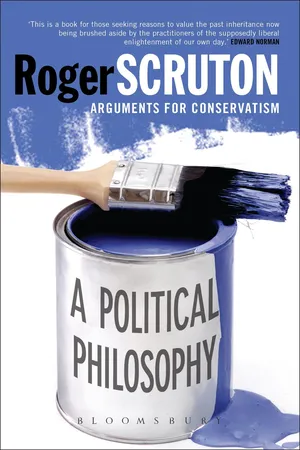

Over the past twenty years, Roger Scruton has been developing a conservative view of human beings, society and culture. The tone of this book is positive and the arguments are recommendations with the aim of convincing the reader that rumours of the death of Western civilisation are greatly exaggerated. Much of our present self doubt, argues Scruton, is brought about by the Darwinian theory of evolution. Darwin encourages us to see human emotion as a reproductive strategy. This is a perspective which Scruton attacks vehemently especially in its modern proponents- Desmond Morris and Richard Dawkins. This the author believes undermines the belief in freedom and the moral imperatives that stem from it.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access A Political Philosophy by Roger Scruton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Political Philosophy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Conserving Nations

Democracies owe their existence to national loyalties – the loyalties that are supposedly shared by government and opposition, by all political parties and by the electorate as a whole. Wherever the experience of nationality is weak or non-existent democracy has failed to take root. For without national loyalty opposition is a threat to government, and political disagreements create no common ground. Yet everywhere the idea of the nation is under attack – either despised as an atavistic form of social unity, or even condemned as a cause of war and conflict, to be broken down and replaced by more enlightened and more universal forms of jurisdiction.

We in Europe stand at a turning point in our history. Our parliaments and legal systems still have territorial sovereignty. They still correspond to historical patterns of settlement that have enabled the French, the Germans, the Spaniards, the British and the Italians to say ‘we’ and to know whom they mean by it. The opportunity remains to recuperate the legislative powers and the executive procedures that formed the nation states of Europe. At the same time, the process has been set in motion that would expropriate the remaining sovereignty of our parliaments and courts, that would annihilate the boundaries between our jurisdictions, that would dissolve the nationalities of Europe in a historically meaningless collectivity, united neither by language, nor by religion, nor by customs, nor by inherited sovereignty and law. We have to choose whether to go forward to that new condition, or back to the tried and familiar sovereignty of the territorial nation state.

However, our political elites speak and behave as though there were no such choice to be made. They refer to an inevitable process, to irreversible changes, and, while at times prepared to distinguish a ‘fast’ from a ‘slow’ track into the future, they are clear in their minds that these two tracks lead to a single destination – the destination of transnational government, under a common system of law, in which national loyalty will be no more significant than support for a local football team.

My case is not that the nation state is the only answer to the problems of modern government, but that it is the only answer that has proved itself. We may feel tempted to experiment with other forms of political order. But experiments on this scale are dangerous, since nobody knows how to predict or to reverse the results of them. The French, Russian and Nazi Revolutions were bold experiments; but in each case they led to the collapse of legal order, to mass murder at home and to belligerence abroad. The wise policy is to accept the arrangements, however imperfect, that have evolved through custom and inheritance, to improve them by small adjustments, but not to jeopardize them by large-scale alterations the consequences of which nobody can really envisage. The case for this approach was unanswerably set before us by Burke in his Reflections on the French Revolution, and subsequent history has repeatedly confirmed his view of things. The lesson that we should draw, therefore, is that since the nation state has proved to be a stable foundation of democratic government and secular jurisdiction, we ought to improve it, to adjust it, even to dilute it, but not to throw it away.

The initiators of the European experiment – both the self-declared prophets and the behind-the-doors conspirators – shared a conviction that the nation state had caused the two world wars. A united states of Europe seemed to them to be the only recipe for lasting peace. This view is for two reasons entirely unpersuasive. First, it is purely negative: it rejects nation states for their belligerence, without giving any positive reason to believe that transnational states will be any better. Second, it identifies the normality of the nation state through its pathological versions. As Chesterton has argued about patriotism generally, to condemn patriotism because people go to war for patriotic reasons is like condemning love because some loves lead to murder. The nation state should not be understood in terms of the French nation at the Revolution or the German nation in its twentieth-century frenzy. For those were nations gone mad, in which the sources of civil peace had been poisoned and the social organism colonized by anger, resentment and fear. All Europe was threatened by the German nation, but only because the German nation was threatened by itself. Nationalism is part of the pathology of national loyalty, not its normal condition. Who in Europe has felt comparably threatened by the Spanish, Italian, Norwegian, Czech or Polish forms of national identity, and who would begrudge those people their right to a territory, a jurisdiction and a sovereignty of their own?

Left-liberal writers, in their reluctance to adopt the nation as a social aspiration or a political goal, sometimes distinguish nationalism from ‘patriotism’ – an ancient virtue extolled by the Romans and by those like Machiavelli who first made the intellectual case for modern secular jurisdiction.1 Patriotism, they argue, is the loyalty of citizens, and the foundation of ‘republican’ government; nationalism is a shared hostility to the stranger, the intruder, the person who belongs ‘outside’. I feel some sympathy for that approach. Properly understood, however, the republican patriotism defended by Machiavelli, Montesquieu and Mill is a form of national loyalty: not a pathological form like nationalism, but a natural love of country, countrymen and the culture that unites them. Patriots are attached to the people and the territory that are theirs by right; and patriotism involves an attempt to transcribe that right into impartial government and a rule of law. This underlying territorial right is implied in the very word – the patria being the ‘fatherland’, the place where you and I belong and to which we return, if only in thought, at the end of all our wanderings.

Territorial loyalty, I suggest, is at the root of all forms of government where law and liberty reign supreme. Attempts to denounce the nation in the name of patriotism therefore contain no real argument against the kind of national sovereignty that I shall be advocating.2 I shall be defending what Mill called the ‘principle of cohesion among members of the same community or state’, and which he distinguished from nationalism (or ‘nationality, in the vulgar sense of the term’), in the following luminous words:

We need scarcely say that we do not mean nationality, in the vulgar sense of the term; a senseless antipathy to foreigners; indifference to the general welfare of the human race, or an unjust preference for the supposed interests of our own country; a cherishing of bad peculiarities because they are national, or a refusal to adopt what has been found good by other countries. We mean a principle of sympathy, not of hostility; of union, not of separation. We mean a feeling of common interest among those who live under the same government, and are contained within the same natural or historical boundaries. We mean, that one part of the community do not consider themselves as foreigners with regard to another part; that they set a value on their connexion – feel that they are one people, that their lot is cast together, that evil to any of their fellow-countrymen is evil to themselves, and do not desire selfishly to free themselves from their share of any common inconvenience by severing the connexion.3

The phrases that I would emphasize in that passage are these: ‘our own country’, ‘common interest’, ‘natural or historical boundaries’ and ‘[our] lot is cast together’. Those phrases resonate with the historical loyalty that I shall be defending. To put the matter briefly: the case against the nation state has not been properly made, and the case for the transnational alternative has not been made at all. I believe, therefore, that we are on the brink of decisions that could prove disastrous for Europe and for the world, and that we have only a few years in which to take stock of our inheritance and to reassume it. Now more than ever do those words of Goethe’s Faust ring true for us:

Was du ererbt von deinen Vätern hast,

Erwirb es, um es zu besitzen.

What you have inherited from your forefathers, earn it, that you might own it. We in the nation states of Europe need to earn again the sovereignty that previous generations so laboriously shaped from the inheritance of Christianity, imperial government and Roman law. Earning it, we will own it, and so be at peace within our borders.

Citizenship

Never in the history of the world have there been so many migrants. And almost all of them are migrating from regions where nationality is weak or non-existent to the established nation states of the West. They are not migrating because they have discovered some previously dormant feeling of love or loyalty towards the nations in whose territory they seek a home. On the contrary, few of them identify their loyalties in national terms and almost none of them in terms of the nation where they settle. They are migrating in search of citizenship – which is the principal gift of national jurisdictions, and the origin of the peace, law, stability and prosperity that still prevail in the West.

Citizenship is the relation that arises between the State and the individual when each is fully accountable to the other. It consists in a web of reciprocal rights and duties, upheld by a rule of law which stands higher than either party. Although the State enforces the law, it enforces it equally against itself and against the private citizen. The citizen has rights which the State is duty-bound to uphold, and also duties which the State has a right to enforce. Because these rights and duties are defined and limited by the law, citizens have a clear conception of where their freedoms end. Where citizens are appointed to administer the State, the result is ‘republican’ government.4

Subjection is the relation between the State and the individual that arises when the State need not account to the individual, when the rights and duties of the individual are undefined or defined only partially and defeasibly, and when there is no rule of law that stands higher than the State that enforces it. Citizens are freer than subjects, not because there is more that they can get away with, but because their freedoms are defined and upheld by the law. People who are subjects naturally aspire to be citizens, since a citizen can take definite steps to secure his property, family and business against marauders, and has effective sovereignty over his own life. That is why people migrate from the states where they are subjects, to the states where they can be citizens.

Freedom and security are not the only benefits of citizenship. There is an economic benefit too. Under a rule of law contracts can be freely engaged in and collectively enforced. Honesty becomes the rule in business dealings, and disputes are settled by courts of law rather than by hired thugs. And because the principle of accountability runs through all institutions, corruption can be identified and penalized, even when it occurs at the highest level of government.

Marxists believe that law is the servant of economics, and that ‘bourgeois legality’ comes into being as a result of, and for the sake of, ‘bourgeois relations of production’ (by which is meant the market economy). This way of thinking has been so influential that even today it is necessary to point out that it is the opposite of the truth. The market economy comes into being because the rule of law secures property rights and contractual freedoms, and forces people to account for their dishonesty and for their financial misdeeds. That is another reason why people migrate to places where they can enjoy the benefit of citizenship. A society of citizens is one in which markets flourish, and markets are the precondition of prosperity.

A society of citizens is a society in which strangers can trust one another, since everyone is bound by a common set of rules. This does not mean that there are no thieves or swindlers; it means that trust can grow between strangers, and does not depend upon family connections, tribal loyalties or favours granted and earned. This strikingly distinguishes a country like Australia, for example, from a country like Kazakhstan, where the economy depends entirely on the mutual exchange of favours, among people who trust each other only because they also know each other and know the networks that will be used to enforce any deal.5 It is also why Australia has an immigration problem, and Kazakhstan a brain-drain.

As a result of this, trust among citizens can spread over a wide area, and local baronies and fiefdoms can be broken down and overruled. In such circumstances markets do not merely flourish: they spread and grow, to become co-extensive with the jurisdiction. Every citizen becomes linked to every other, by relations that are financial, legal and fiduciary, but which presuppose no personal tie. A society of citizens can be a society of strangers, all enjoying sovereignty over their own lives, and pursuing their individual goals and satisfactions. Such are Western societies today. They are societies in which you form common cause with strangers, and which all of you, in those matters on which your common destiny depends, can with conviction say ‘we’.

The existence of this kind of trust in a society of strangers should be seen for what it is: a rare achievement, whose pre-conditions are not easily fulfilled. If it is difficult for us to appreciate this fact it is in part because trust between strangers creates an illusion of safety, encouraging people to think that, because society ends in agreement, it begins in it too. Thus it has been common since the Renaissance for thinkers to propose some version of the ‘social contract’ as the foundation of a society of citizens. Such a society is brought into being, so Hobbes, Locke, Rousseau and others in their several ways argue, because people come together and agree on the terms of a contract by which each of them will be bound. This idea resonates powerfully in the minds and hearts of citizens, because it makes the State itself into just another example of the kind of transaction by which they order their lives. It presupposes no source of political obligation other than the consent of the citizen, and conforms to the inherently sceptical nature of modern jurisdictions, which claim no authority beyond the rational endorsement of those who are bound by their laws.

The theory of the social contract begins from a thought-experiment, in which a group of people gather together to decide on their common future. But if they are in a position to decide on their common future, it is because they already have one: because they recognize their mutual togetherness and reciprocal dependence, which makes it incumbent upon them to settle how they might be governed under a common jurisdiction in a common territory. In short, the social contract requires a relation of membership, and one, moreover, which makes it plausible for the individual members to conceive the relation between them in contractual terms. Theorists of the social contract write as though it presupposes only the first-person singular of free rational choice. In fact it presupposes a first-person plural, in which the burdens of belonging have already been assumed.

Membership and Nationality

It is because citizenship presupposes membership that nationality has become so important in the modern world. In a democracy governments make decisions and impose laws on people who are duty-bound to accept them. Democracy means living with strangers on terms that may be, in the short-term, disadvantageous; it means being pr...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1 Conserving Nations

- 2 Conserving Nature

- 3 Eating our Friends

- 4 Dying Quietly

- 5 Meaningful Marriage

- 6 Extinguishing the Light

- 7 Religion and Enlightenment

- 8 The Totalitarian Temptation

- 9 Newspeak and Eurospeak

- 10 The Nature of Evil

- 11 Eliot and Conservatism

- Acknowledgements

- Name Index

- Subject Index

- eCopyright