![]()

1

THE LAND AND ITS PEOPLE

Much of it is covered exclusively with the long leaf pine; not broken, but rolling like the waves in the middle of the great ocean. The grass grows three feet high and hill and valley are studded all over with flowers of every hue. The flora of this section of the State and thence down to the sea board is rich beyond description. Our hortus-siccus, made up on this hurried journey, would feast a botanist for a month.

—John F. H. Claiborne, A Trip through the Piney Woods, 1840

Like the deep sedimentary soils that it rests upon, south Mississippi is composed of many layers. The coastal cities of Biloxi and Gulfport contour their shorelines along the Gulf of Mexico with brightly lit casinos and miles of imported sandy beach. These waterside cities enjoy a steady industry of fishing, tourism, and ship building. But drive just a few miles north from these resort destinations and you will soon find yourself in the thick of the Piney Woods landscape. Lumberton, Kiln, and Fruitland Park are just a few of the small towns you encounter embellished with names that reveal their agricultural or timber origins. The people here are intimately tied to the soil with still-popular pastimes of hunting and fishing along the ample river systems. It is a sylvan land.

Connecting these small community centers are miles of two-lane asphalt roads that wind along abundant cattle pastures, forests, and scattered homesteads. Slender pine trunks line the roadsides and create alternating rhythms of sun and shadow in late afternoons that can dangerously lull a driver to sleep. Mississippi is often misunderstood nationally, and it is far too simple to believe you could sum up this region through the windshield. You must dig deep and fully engage the senses to understand what this land has to offer.

As you step out from the car, you are immediately confronted with the vagaries of this place, and there is no mistake that you have landed squarely in Mississippi. If it is midsummer, your clothes will abruptly wither in the moist subtropical heat and humidity. The air is almost thick enough to see and taste. Everything that surrounds you seems to be a little more magnified and larger than life. The leaves of southern magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora) and bigleaf magnolia trees (Magnolia macrophylla) are not just large here, but enormous. Cicadas do not merely buzz loudly in the trees but pierce the air with their droning sound. The unmitigated summer sun creates such an intense light that both animals and humans must retire midday into their warrens.

Mississippi’s landscape has inspired noted fiction writers such as Eudora Welty, William Faulkner, and John Grisham. In a land so richly textured, authors merely have to reach out and pick their muse. If one looks closely, the stories are written into the land. Narratives are abundantly embedded in the interstices of the soil, water, and air and help give form to place. It is not uncommon to see slivers of the past all around—in the ruts of previously well traveled roadways now grown to forest; the brick steps that remain long after the house is gone; a rambling rose that was once planted by a forgotten hand. The southern landscape teems with the specters of those who have walked here before.

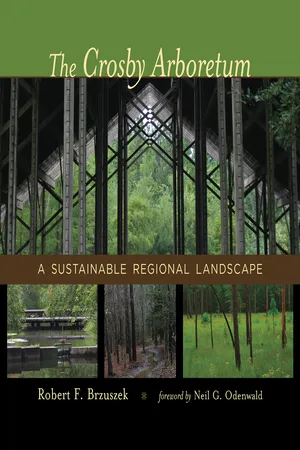

The Crosby Arboretum is a place where people can see and experience representations of the native environments of the Gulf Coastal landscape. The arboretum appears to be a remnant natural area, with woodlands, wetlands, and grasslands untouched by people. Yet, while inspired by nature, it was carefully shaped and thoughtfully guided by human interventions. It features natural-appearing places, yet little is natural. It is not a virgin landscape as in a preserve, but instead one that has healed from the effects of intensive farming and forestry. The Crosby Arboretum presents a rich case study of a human dialogue with the land. Rather than embracing prior worldviews that humans are somehow separate from the natural world, it is instead a bold conviction that humans interact with and are a partner of nature. At Crosby, the existing landscape was studied and understood and natural process was embraced. Historically, many botanic gardens and arboreta feature landscape exhibits that are formally structured and maintained to the smallest detail. The Crosby Arboretum is ordered in its layout yet allows for ecological process to occur.

The Crosby Arboretum is a place born from the land and its people. Unlike many notable architectural and landscape edifices, the Crosby Arboretum did not spring from the grand vision of just one person. Its design derived instead from a synergistic blend of the leading minds in the arts and sciences. Biologists, geologists, landscape architects, architects, horticulturists, artists, and foresters—all had gathered around this site to dream of its potential and to envision the type of landscape it could become. When the design for Crosby Arboretum’s Master Plan was presented an Honor Award in 1991 by the American Society of Landscape Architects, the arboretum was described by the jury as the “first fully realized ecological garden in the country.”1 But in order to appreciate this unique garden that was built from the land, we first need to understand how the land was shaped and who lived there.

THE DISTANT PAST

The place that would one day become the Gulf Coast landscape once lay sleeping under a shallow blue sea. Spiraled ammonites and fierce aquatic reptiles such as mosasaurs swam freely above the ocean floors that over 70 million years later became the busy cities of Pensacola, New Orleans, and Houston.2 Countless sunsets saw the nearby Appalachian and Ozark mountain ranges slowly wear down to the rounded mounds they resemble today. From these tall peaks, massive amounts of erosion occurred, so much so that the entirety of today’s lower Coastal Plain was built upon thousands of feet of sediments, and the land emerged from the sea. It has been estimated that over the past 60 million years over 20,000 feet of sediments has been deposited in the central Gulf region.3 As climates changed and glaciers inched their way across northern lands, rich soils and gravels coursed southward through ancient streambeds. Incessant winds blew a fine powdery dust from these faraway glacial moraines to lightly touch down along the Mississippi River corridor. During the Pleistocene Epoch, over two and a half million years ago, the Gulf Coastal Plain was mostly formed. Sand and silt grains steadily built the plain into a flat sedimentary landscape of mud. In many ways, the coastal landscape still bears a striking resemblance to the sea bottom that it once was—mostly flat with little elevation change, deep layers of sand and silt, and an infusion of water and waterways.

While the Gulf Coast can be defined in many ways, it has one unfailing characteristic that has recurred through the ages—an endless propensity for change. Here the rivers shift across the landscape like untamed beasts and repeatedly seek new courses. As they race along, they carve sediments from peaks and valleys, only to deposit them elsewhere. Even the large body of water known as the Gulf of Mexico couldn’t quite make up its mind as its shoreline edge continuously shifted in a slow yet persistent fashion. Over eons, as the Earth’s climate warmed and cooled, the vast northern ice sheets would wax and wane in size, causing the retreat or advancement of the world’s oceans.4 Like the shapeshifter that it is, the Gulf Coast region has changed continuously over geologic time. This region has one of the most resilient ecosystems on the North American continent because of its remarkable ability to rebound with new life.

Many natural forces keep the Gulf Coast landscape in a constant state of flux. The Gulf of Mexico interacts with its adjacent plain, contributing not only sea breezes and high humidity but also heavy rains, often in excess of sixty inches per year. Much of the immediate coastal area is wetland, and the vegetation is adapted to periods of nearly continuously wet soils. With unsettling regularity, fierce tropical storms and their accompanying tornadoes and lightning dance across the land. Studies of historic hurricane paths show most of the Gulf Coast landscape hit with alarming regularity. One study of historic weather patterns in Alabama concluded that hurricanes have visited the same areas on average every 318 years.5 Massive hurricanes, monstrous storms, record floods, debilitating droughts, and devastating fires ravage the land here on so frequent a basis that old-growth forests hardly exist. Only in the most protected of deep coves and river basins of the Southeast are older woodlands typically found. This continual churning of fires and flood, tornadoes and hurricanes, droughts and devastation, gave rise to one of the most beautiful yet resilient landscapes in North America today—the Gulf Coast Piney Woods.

When Europeans arrived to colonize the North American continent over half a millennium ago, a vast pine savanna (a flat, open grassland with scattered trees) stretched inland along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts.6 A nearly continuous band of pine had formed from the sand ridges of eastern Texas to the flat terraces of Virginia, broken apart only by the river valleys and wetlands, where hardwood trees abound.7 This was the landscape of the majestic longleaf pine forest (Pinus palustris). Written accounts from the 1860s describe Mississippi as a landscape of pines and other trees with a shimmering understory of grasses and wildflowers.8 Longleaf pines bend and sway in strong winds and can live the longest of all the pines.9 If a pine can stand up to the fiercest storms, it may survive for hundreds of years. Mississippi’s champion longleaf pine resides today in Jasper County and reaches 115 feet in height and nearly ten feet in circumference. This monster of a tree is estimated to exceed four hundred years in age.10 Southern writer Janisse Ray, after visiting an ancient longleaf pine grove in Georgia, summed up the scene aptly: “Nothing is more beautiful, nothing more mysterious, nothing more breathtaking, nothing more surreal.”11 Just a few hundred years ago, the original longleaf pine range encompassed over ninety million acres. Today, with less than 3 percent of its original holdings left in very fragmented areas, the longleaf pine forest is one of the most endangered ecosystems in North America.12

A longleaf pine forest is a unique ecological system. It shelters some of the most interesting and specialized plant communities in the world, such as the southeastern pitcher plant bog. This carnivorous plant–dominated wetland occurs just downslope from longleaf pine ridges, and these bogs are among the most biodiverse landscape systems on our continent.13 But the longleaf pine region shelters many such diverse communities. Twenty-nine endangered or threatened animal species live within longleaf pine forests, and they harbor at least 122 species of threatened or endangered plants.14 These specialized life forms are fine-tuned to the intricate characteristics that make a longleaf forest tick. Gopher tortoises (a land tortoise of ancient lineage) need occasional Piney Woods wildfires to stimulate the herbaceous plants and fruit that they consume. In the absence of fire, woody plants dominate the landscape and the gopher tortoises leave, in search of another place to live. Gopher tortoises are termed a keystone species, which means that hundreds of other species depend upon its existence. Up to 360 species of wildlife utilize the extensive tunnels that the threatened gopher tortoises dig.15

Other animals likewise depend on the continued existence of the longleaf pine forest. Federally endangered red-cockaded woodpeckers build their nests in the trunks of living, older pine trees. They drill holes in the trees with their bills so that the sticky tree sap will deter predators such as snakes. It has been observed that red-cockaded woodpeckers typically use trees that are at least sixty years old.16 Since most forestry operations are on much shorter crop rotations, often less than thirty years, suitable red-cockaded pine habitat is now rare in the Southeast.

Longleaf pines take longer to grow than other pines. Today, most landowners and foresters tend to plant the quick-growing loblolly (Pinus taeda) or slash pine (P. elliottii). However, there has been a resurgence of planting longleaf pines in forestry operations. Numerous nonprofit groups have pledged to increase the longleaf pine range through various restoration activities. For instance, the staff at the Crosby Arboretum has replanted many longleaf pines in the Savanna Exhibit to better showcase this dwindling forest type.

Fire, usually thought of as destructor, gives birth to the Piney Woods landscape. Natural fires are caused by lightning, and lightning fires once burned frequently and unchecked through the lands. A study by J. M. Huffman assessed old pine stumps that contained abundant fire scars, concluding that wildfires have occurred regularly in five-year periods.17 These frequent fires burned out the hardwood trees and underbrush, allowing dense carpets of grasses, wildflowers, and the fire-tolerant pines to flourish. Early explorers and colonists of the Gulf Coast found these open pine forests easy to travel in and hunt for game. Captain John Smith, the famous Jamestown settler, once wrote that “a man may gallop a horse amonst these woods any waie, but where the creeks and Rivers shall hinder.”18 W. C. Corsan, an English merchant who traveled at the time of the Civil War via rail from New Orleans to Jackson, Mississippi, noted the abundant open pine woods and magnificent rolling lands of southern Mississippi.19

In addition to lightning ignitions, fires were set in the landscape by indigenous peoples for many thousands of years. Tribes would use fire to open land up for better visibility, to clear fields for crops and agriculture, and for hunting purposes.20 William Bartram, who traveled the southeastern United States in the 1770s, observed Native Americans setting the landscape on fire. He wrote in his Travels through North and South Carolina, Georgia, East and West Florida, the Cherokee Country, etc. that fires occurred rather often, and “the trees and shrubs which cover these extensive ...