![]() ARCHITECTURAL GEOGRAPHIES AND THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

ARCHITECTURAL GEOGRAPHIES AND THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT![]()

ON IMPORTATION AND ADAPTATION

Creole Architecture in New Orleans

“Creole” is a famously complex facet of Louisiana culture, whether as a noun implying an ethnic identity or an adjective describing anything from tomatoes to cooking. Ask ten New Orleanians to define “Creole” and you’ll likely get thirty different answers.

So too Creole architecture: explaining what makes a house Creole defies one unequivocal answer. As an emergent tradition rendered by experimentation and adaptation rather than an inscribed order, Creole architecture is better understood through its evolution and transformation.

One thing is certain: most buildings in colonial New Orleans, at least until the 1790s, epitomized Creole architecture, and they exhibited an inventory of signature traits and construction methods. These included walls made of brick or mud mixed with moss (bousillage), set within a load-bearing timber frame covered with clapboards; an oversized “Norman” roof, usually hipped and double-pitched; and spacious wooden galleries supported with delicate colonnades and balustrades, which served as intermediary space between indoors and outdoors. Staircases were located outside on the gallery, chimneys were centralized, apertures had French doors or shutters, hallways and closets were all but unknown, and the entire edifice was raised on piers above soggy soils.

Such buildings were distributed across today’s French Quarter by the hundreds in the mid-1700s and over a thousand later in the century. Roughly half were set back from the street, and nearly all had open space around them, used for vegetable gardens, chicken coops, and rabbit hutches and surrounded by picket fences. It was a rather bucolic environment, with the appearance of a French West Indian village. Wrote English captain Philip Pittman during his 1765 visit, “most of the houses are . . . timber frames filled up with brick” and “one floor, raised about eight feet from the ground, with large galleries round them. . . . It is impossible to have any subterraneous buildings, as they would be constantly full of water.”

The best surviving examples of this early phase of Creole architecture in the French Quarter are Madame John’s Legacy at 632 Dumaine Street and the Ossorno House at 913 Governor Nicholls, both of which date to the 1780s, and Lafitte’s Blacksmith Shop on Bourbon Street at St. Philip, whose construction is undocumented but perhaps dates to the 1770s. A dozen or so similar buildings survive elsewhere in the city, including the Old Spanish Customs House (1784) and Pitot House (1805) on Bayou St. John and the Lombard House (1826) in Bywater. (The Old Ursuline Convent at 1111 Chartres, completed in 1753 and now the city’s oldest structure, represents a French Colonial institutional style typical of France during the reign of Louis XV, and embodies many Creole traits, including the steep double-pitched hipped roof.)

Lafitte’s Blacksmith Shop on Bourbon Street at St. Philip, probably built in the 1770s and one of the few surviving specimens of West Indian–influenced “first generation” Creole architecture. Photograph by Richard Koch, 1934, Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress.

Where did Creole architecture come from? Researchers generally agree this tradition was not “invented” locally in response to environmental conditions (hot weather, heavy rain, wet soils), as is often supposed. Rather, it arrived courtesy of newcomers who brought with them all their other cultural customs, including building know-how, and modified them to local conditions through incremental experimentation. But by what routes and from which source regions?

One theory views Louisiana Creole architecture as a derivative of French Canadian houses originating from the Normandy region of France (hence the term “Norman roof”) and later modified to local conditions and needs. This proposition suggests Creole architecture diffused down the Mississippi Valley. Another theory emphasizes influences directly from France to Louisiana. A third and favored explanation sees Creole architecture as an extraction from a West Indian cultural milieu, itself a product of European, indigenous, and African influences, such as the Arawak Indian Bohio hut and possibly West Africa’s Yoruba hut. This hypothesis suggests that Creole architecture diffused primarily up the Mississippi Valley from the Caribbean and beyond, rather than down from Canada or directly from France. It thus situates New Orleans at the nexus of the “Creole Atlantic” and the North American interior. Louisiana State University anthropologist Jay D. Edwards viewed West Indian influence consequential enough to warrant recognition of the Caribbean region as “another major cultural hearth for the domestic architecture of eastern North America,” along with England, France, Spain, Germany, West Africa, Holland, Scandinavia, and other places.

Madame John’s Legacy at 632 Dumaine Street, built in 1788 in the early Creole style and now one of the last best examples of eighteen-century New Orleans residential architecture. Photograph 1930s, courtesy Library of Congress.

Circumstances changed in the late 1700s, and so would Creole architecture. A massive fire in 1788 destroyed 856 of New Orleans’s Creole housing stock, and a second blaze in 1794 destroyed another 212. Spanish administrators responded with new building codes designed to prevent fires, mandating, according to Cabildo records, new houses to be “built of bricks and a flat roof or tile roof,” and extant houses to be strengthened “to stand a roof of fire-proof materials,” their beams covered with stucco. “[All] citizens must comply with these rules,” the dons decreed.

The Old Absinthe House (1806, seen here around 1900), corner of Bourbon and Bienville, representative of a second generation of Creole architecture, more urban and with greater Spanish influence. Photograph courtesy Library of Congress.

The fires and codes largely ended that first phase of rustic, wooden Creole houses in New Orleans proper, though they would persist in rural areas. They would become even more unsuitable in the years following the Louisiana Purchase and American dominion, during which the city’s population quintupled by the 1820s. Land values rose, housing density increased, and picket fences and rabbit hutches disappeared from the inner city.

But Creoles—that is, locally born people, mostly francophones—still predominated, and Creole builders continued to erect “creolized” structures now exhibiting Spanish and Anglo-American influences, programmed to the needs of a budding metropolis.

Thus, in the early 1800s, a second phase of Creole architecture emerged, and it constituted the Creole cottages we know today (which are really an adaptation of first-generation Creole houses to more urbanized settings) as well as large brick common-wall townhouses and storehouses featuring arched openings, wrought-iron balconies, an elegantly Spartan stucco facade, and a porte cochère carriageway leading to a rear courtyard. What once felt like a Caribbean village was now starting to look like a Mediterranean city. Wrote Scottish visitor Basil Hall in 1828, “[w]hat struck us most [about New Orleans] were the old and narrow streets, the high houses, ornamented with tasteful cornices, iron balconies, and many other circumstances peculiar to towns in France and Spain.”

Typical courtyard of a “second generation” Creole townhouse on Royal Street, built in the early 1800s and seen here circa 1900. Photograph courtesy Library of Congress.

Contrast Hall’s quote to that of Philip Pittman in 1765, above, and that’s the difference between first-generation “country Creole” and second-generation “city Creole” architecture. There are, by my count, 740 examples of this latter phase still standing in the French Quarter, mostly dating to the 1810s–30s. We call them “Creole” today for two reasons: because they were creolized—that is, adapted to local conditions—and because folks regularly called them Creole back then. Among the most splendid specimens of these second-phase or second-generation Creole townhouses may be seen along 612–624 Royal Street.

But Creole people in this era increasingly found themselves competing with ever-growing populations of Anglo-Americans and immigrants, who imported their own cultural preferences. Architecturally, this meant the rise of Neoclassicism, particularly Greek Revival.

This was also the era when architecture developed into a specialized profession with standardized techniques, replacing the lay tradesmen and “housewrights” of old. Card-carrying architects such as James Gallier Sr. and Henry Howard, both from Ireland by way of New York, and the New York–born brothers James and Charles Dakin all set up shop in New Orleans in the 1830s, and they weren’t designing Creole buildings.

To some researchers, the Neoclassical trend set the old Creole customs on a trajectory of decline. “The truly significant period of New Orleans architecture was brought into jeopardy by the [Louisiana] Purchase and brought to an end by the Civil War,” wrote the late architect and preservationist James Marston Fitch. “The Americanization of the Crescent City has long been completed, at least architecturally; and the whole nation is the poorer for it.”

An alternative interpretation holds that, rather than wiping them out, the city’s mid-nineteenth-century Americanization drove Creole designs into yet another evolutionary phase. That phase entailed the dovetailing of one local innovation—the rotation of the traditional Creole cottage such that its roofline, typically parallel to the street, became perpendicular to it—with a related idea for elongated houses imported from Haiti starting in 1809, when over nine thousand Haitian refugees arrived at New Orleans. What resulted were long narrow houses, the type that would later be nicknamed “shotguns.”

After the Civil War, as population density increased and demand for rental stock rose, builders erected shotgun houses by the thousands—singles, doubles, camelbacks, whatever the market demanded and space allowed. Those built in the late 1800s continued two key interior traits shared by that first generation of circa-1700s Creole architecture: center chimneys and no hallways. Our shotgun houses today retain a striking resemblance to the Ti-kay (“little houses”) dwellings seen throughout modern Haiti, and the relationship is probably not coincidental.

Traditional shotguns went out of style in the early twentieth century, by which time we can fairly say that Creole architecture had faded away. Yet certain traits endure today in the form of pastiche, such as the Norman roofs popular in many modern Louisiana subdivisions, and the ample porches and galleries seen in New Urbanist communities.

More so, Creole architecture survives in modern New Orleans through the efforts of the preservationist movement, which recognized its value long before most residents and leaders did. New Orleanians are deeply indebted to preservationists for keeping within our stewardship the nation’s largest concentration of this beautiful tradition.

![]()

SHOTGUN GEOGRAPHY

Theories on a Distinctive Domicile

Few elements of the New Orleans cityscape speak to the intersection of architecture, sociology, and geography so well as the shotgun house. Once scorned, now cherished, shotguns shed light on patterns of cultural diffusion, construction methods, class and residential settlement patterns, and social preferences for living space.

The shotgun house is not an architectural style; rather, it is a structural typology—what folklorist John Michael Vlach described as “a philosophy of space, a culturally determined sense of dimension.” A typology, or type, may be draped in any style. Thus we have shotgun houses adorned in Italianate, Eastlake, and other styles, just as there are Creole and Federalist-style townhouses, and Spanish colonial and Greek Revival cottages.

Tradition holds that the name “shotgun” derives from the notion of firing birdshot through the front door and out the rear without touching a wall, a rustic allusion to its linearity and room-to-room connectivity. The term itself postdates the shotgun’s late-nineteenth-century heyday, not appearing in print until the early twentieth century.

Vlach defined the prototypical shotgun as “a one-room wide, one-story high building with two or more rooms, oriented perpendicularly to the road with its front door in the gable end, [although] aspects such as size, proportion, roofing, porches, appendages, foundations, trim and decoration” vary widely. Its most striking exterior trait is its elongated shape, usually three to six times longer than wide. Inside, what is salient is the lack of hallways: occupants need to walk through private rooms to access other rooms.

Theory contends that cultures that produced shotgun houses (and other residences without hallways, such as Creole cottages) tended to be more gregarious, or at least unwilling to sacrifice valuable living space for the purpose of occasional passage. Cultures that valued privacy, on the other hand, were willing to make this trade-off. Note, for example, how privacy-conscious peoples of Anglo-Saxon descent who arrived at New Orleans in the early nineteenth century brought with them the American center-hall cottage and side-hall townhouse, in preference over local Creole designs.

Academic interest in the shotgun house dates from Louisiana State University geographer Fred B. Kniffen’s field research in the 1930s on Louisiana folk housing. He and other researchers have proposed a number of hypotheses explaining the origin and distribution of this distinctive house type. One theory, popular with tour guides and amateur house-watchers, holds that shotgun houses were designed in New Orleans in response to a real estate tax based on frontage rather than square footage, motivating narrow structures. There’s one major problem with this theory: no one can seem to find that tax code.

Could the shotgun be an architectural response to narrow urban lots? Indeed, you can squeeze in more structures with a slender design. But why then do we see shotguns in rural fields with no such limits?

Could it have evolved from indigenous palmetto houses or Choctaw huts? Unlikely, given their appearance in the Caribbean and beyond.

Could it have been independently invented? Roberts & Company, a New Orleans sash and door fabricator formed in 1856, developed blueprints for prefabricated shotgun-like houses in the 1860s to 1870s and even won awards for them at international expositions. But then why do we see “longhouses” in the rear of the French Quarter and in Faubourg Tremé as early as the 1810s?

Or, alternately, did the shotgun diffuse from the Old World as peoples moved across the Atlantic and brought with them their building culture, just as they brought their language, religion, and foodways? Vlach noted the abundance of shotgun-like longhouses in the West Indies, and traced their essential form to the enslaved populations of Saint-Domingue (now Haiti) who had been removed from the western and central African regions of Guinea and Angola. His research identified a gable-roofed housing stock indigenous to the Yoruba peoples, which he linked to similar Ti-kay structures in modern Haiti with comparable rectangular shapes, room juxtapositions, and ceiling heights.

Vlach hypothesizes that the 1809 exodus of Haitians to New Orleans after the Saint-Domingue slave insurrection of 1791–1803 brought this vernacular house type to the banks of the Mississippi. “Haitian émigrés had only to continue in Louisiana the same life they had known in St. Domingue,” he wrote. “The shotgun house of Port-au-Prince became, quite directly, the shotgun house of New Orleans.”

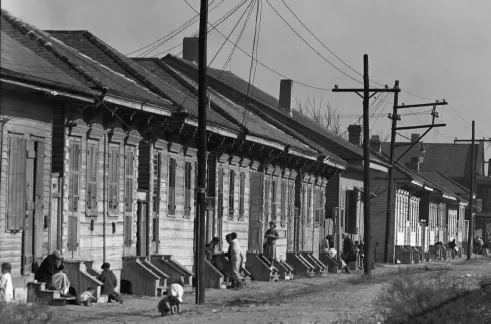

Late-nineteenth-century shotgun houses in the Fifth Ward, seen here in the 1930s. Photograph by Walker Evans, courtesy Library of Congress.

The distribution of shotgun houses throughout Louisiana gives indirect support to the diffusion argument. Kniffen showed in the 1930s that shotguns generally occurred along waterways in areas that tended to be more francophone in their culture, higher in their proportions of people of African and Creole ancestry, and older in their historical development.

Beyond state boundaries, shotguns occur throughout the lower Mississippi Valley, correlated with antebellum plantation regions and with areas that host large black populations. They also appear in interior southern cities, most notably Louisville, Kentucky, which comes a distant second to New Orleans in terms of numbers and stylistic variety. If in fact the shotgun diffused from Africa to Haiti through New Orleans and up the Mississippi and Ohio valleys, this is the distribution we would expect to see.

Clearly, poverty abets cultural factors in explaining this pattern. ...