![]()

1

Public Opinion Polling in a Digital Age

Meaning and Measurement

KIRBY GOIDEL

Since 1936 when George Gallup bested the Literary Digest straw poll, public opinion in American politics has been synonymous with scientifically based opinion polling. Public opinion, in this respect, has been defined primarily as the aggregation of privately held individual opinions as revealed through carefully constructed questions posed to randomly selected samples. Such a definition fit perfectly within the context of the broadcast era of American politics in which information was distributed through a small number of channels (primarily the major networks and daily newspapers) and the opportunities for public feedback were limited. Public opinion was the mass audience, mostly passive and reactive to elite communications. In the 2009 Breaux Symposium, we considered how well this definition of public opinion, as well as its measurement through polling, holds up in a digital age with almost unlimited information choices and opportunities for public feedback. This much is clear: survey research is going through its most significant transition since the development and widespread adoption of probability-based sampling in 1936. What emerges from this transition is likely to differ in important ways from the mainstay of survey research from 1974 to the present—landline telephone interviews based on random digit dialing.

Over the past several years, pollsters have struggled with significant challenges to the credibility of their work, including declining response rates and an increased reliance on cell phones for interpersonal communication. While it might be an overstatement to suggest that the polling industry is in the midst of a crisis, the credibility of public opinion research has, with good reason, been increasingly called into question. Pollsters have generally confronted these challenges as technical problems with technical solutions. A growing cell-phone-only population, for example, could be addressed by sampling from banks of cell phone numbers or through address-based sampling.

The technical difficulties confronting pollsters may, however, reflect a more interesting possibility: public opinion in a digital age may be more elusive and consequently less easily measured than in the past. In a digital age, aggregating privately held individual opinions may be insufficient to the task of capturing an increasingly dynamic and interactive public. In this respect, the growth and widespread adoption of digital media—the Internet, social networking sites, blogs, Twitter, cell phones, and now smart phones—have increased not only the amount and diversity of information available to citizens but also the opportunities for political participation and opinion expression. The conversation of politics in this environment is ongoing and incomplete and not easily captured in the snapshot of the public mood provided by opinion polls.

This may sound like a narrow distinction, but it is of considerable theoretical and practical importance. In the first instance, the solution is a better telescope, a more refined or precise scientific instrument. Overcome the technical challenges (e.g., dual-frame sampling to capture cell-phone-only and cell-phone-mostly respondents) and the problem is solved. In the second instance, the very nature of the phenomena under study is different, perhaps because the initial theorizing was limited in scope or perhaps because the old definition is no longer tenable under a new reality. Refined instrumentation in the latter instance will not suffice because what is needed is new theorizing (e.g., Einstein theorizing that light is better described as discrete particles as opposed to waves). But if public opinion is indeed more difficult to capture, an important and lingering question is left open: Why are there so many people conducting so many surveys?

The Proliferation of Polls

There can be little question that scientific opinion polling has fundamentally reshaped the American political landscape. Almost every candidate message is carefully pretested to understand which issues and phrases move candidate support. Elected officials and their advisers pore over poll results to guide policy-making decisions. While it is a myth to suggest that politicians blindly follow polls, poll results unquestionably help to shape political agendas and persuasive messages.

Journalists frequently decry this prefabricated poll-tested politics as inauthentic, but they are hardly immune to the influence or pervasiveness of polling. Indeed, they are the leading cause. The horse race is the mainstay of election coverage as news focuses primarily on who is ahead and by how much. Pity the candidate who does not poll well. He or she gets little or no coverage, finds it nearly impossible to raise money, and is often excluded from media-sponsored debates. Pity as well the candidate or elected official who begins falling in the polls (à la Hillary Clinton in the 2008 Democratic primaries). A decline in public support can drive the campaign narrative, as every act and pronouncement is interpreted in light of a faltering campaign or a failed administration. Most of all, pity the candidate who goes off script and makes an “authentic” error. Missteps—even literally falling off a stage—can be the death knell for aspiring candidates with subsequent coverage driving down candidate support and favorability ratings. Politically, it is much safer to avoid the straight talk express (à la John McCain) and stay on script (à la George W. Bush). Leave aside for now the question of whether polls should play such a prominent role in news coverage and consider this instead: Should polls play such a prominent role when the credibility of polling is increasingly in doubt? And do journalists who cover politics have a sufficient understanding of polling to decipher good polling from bad?

When news coverage does briefly turn to the issues, it is generally placed within the broader framework of campaign strategy and gamesmanship.1 Polling, which could be used to illuminate political issues and public preferences, is instead used as part of an ongoing game in which the news media continuously track who is ahead and who is behind. A new announcement on health care policy, for example, is almost never interpreted as a statement on policy but rather as an effort to shift the campaign agenda onto more favorable turf. Once the campaign is over, news coverage focuses relentlessly on various measures of public approval—from standard presidential approval to more detailed questions on the president’s agenda (e.g., health care reform, the economy, and foreign affairs). Virtually every presidential action or policy position is part of an ongoing referendum of randomly selected samples with added commentary from journalists and pundits. For newspapers with declining circulations, revenue, and staff, opinion polls provide an easy story line or narrative to frame political developments and breaking events.

Nor is the impact of polling limited to politics. Nearly every aspect of human behavior has been the subject of a survey question and subsequent data analysis. Market researchers examine the odds of various purchasing decisions, lump consumers into segments (or clusters) based on buying patterns and lifestyle preferences, and target persuasive messages accordingly. In the political realm, these segments become popularized as soccer moms, security moms, Bubbas, and NASCAR dads and the focus of targeted communications designed to mobilize the political base or persuade cross-pressured voters.

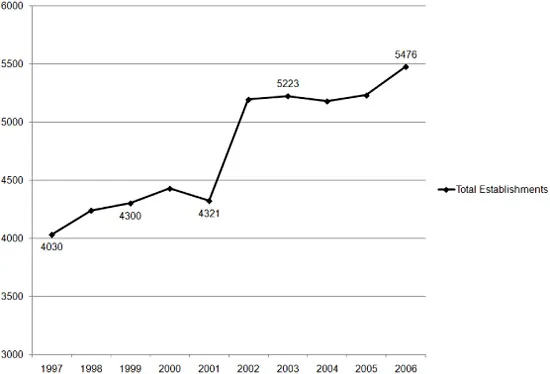

Polls are so pervasive that the sheer number of polls is thought to be a major contributor in driving down survey response. While it is difficult to get exact estimates on the number of polling organizations or the number of polls conducted, Figure 1.1 presents the number of marketing research and public opinion firms as reflected in Census Bureau economic data. Missing from the data are academic survey research centers and polling services provided within larger organizations where survey research is not the primary financial activity. These limitations aside, the trend should be apparent: the number of polling firms and the level of polling activity have increased continuously at least since 1997.

Given the sheer volume of polling and upward trend in activity, it might be surprising to learn that the pollsters have been struggling with challenges to the credibility of their work. First, the public polls purport to measure is increasingly hard to reach as potential respondents rely on technology (e.g., caller ID and answering machines) to screen or block calls from unknown numbers. Wary of telemarketing calls and push polls, they are also less inclined to cooperate when contacted. As a result, reported response rates have declined precipitously over the past several decades to the point where only a quarter of respondents answer the typical telephone survey. Response rates are even lower (often in the single digits) for overnight polls designed to gauge public reactions to political events, presidential speeches, or political debates. Existing research indicates that low response rates may be less of a problem than often feared as nonrespondents do not often deviate substantially from respondents in most surveys, particularly after appropriate poststratification weights are applied to the data.2 Even so, the potential for response bias is a serious concern, and the degree to which it affects the results of any given survey is generally an unknown.

Figure 1.1. Total Marketing Research and Public Opinion and Polling Establishments

Perhaps the more pressing challenge to pollsters has been a growing reliance on cell phones for interpersonal communication. According to some estimates, landline telephone surveys may miss as much as 30 percent of the population—including individuals who have abandoned landline telephones altogether (the cell-only population) and individuals who still have landline phones but rarely or never use them (the cell-mostly population).

Collectively, the challenges confronting survey research and the continued growth of public opinion polling present something of a paradox. Pollsters are increasingly confronting serious challenges to the quality of their data, addressing these challenges increases the costs of conducting survey research, and yet the demand for polling—and the supply of pollsters—have only increased over time. Covering the economics of the polling industry is beyond the scope of the current analysis, but two points are important within this context:

1. Lower barriers, rising costs. The barriers to entering the polling industry have declined significantly over the past decade. Even within the context of traditional landline telephone surveys, software for data collection (CATI) and data analysis (e.g., SPSS, STATA, and SAS) has become more affordable and user-friendly. Automated telephone surveys, also referred to as robo-polls (but more appropriately called interactive voice response, or IVR, polls), make it possible to conduct surveys without the added costs of telephone interviewers. IVR polls do about as well as traditional telephone surveys in predicting the winner of an election, but they provide little or no contextual understanding of campaigns or issues. The situation with Web surveys is even worse: “Essential tools of political polling,” David Hill observed, “are more accessible to the untrained than ever. Online services like SurveyMonkey (an apt label) will probably accelerate the slide of the industry. A clear majority of pollsters today has no formal academic training in the trade.”3 Creating and conducting online polls is easier than ever, requiring little or no understanding of survey research, questionnaire construction, or statistics. Ease of entry also increases the possibility of outright fraud as highlighted by recent allegations of data fabrication. In separate incidents, Strategic Vision and Research 2000 were accused of fabricating data after statistical analyses revealed highly unlikely patterns in the reported results.4 Despite lower barriers to entry, however, the costs of doing quality, rigorous opinion polling have increased substantially. Declining response rates have increased the costs of contacting respondents, as each completed interview requires more time, effort, and money. And while sampling cell phone numbers increases the coverage of surveys, it adds significantly to the overall costs. According to most estimates, cell phone surveys costs three to five times as much as comparable landline surveys.

2. Economic value of survey data. Surveys generally use probability-based sampling to estimate candidate or issue support within a larger population, but carefully constructed surveys may also help political professionals identify which issues and phrases move candidate support and which groups of voters to target with specific campaign appeals. Understanding variations due to question wording, for example, helps to effectively frame candidate issue positions. Survey findings may prove less representative of the overall population but may still be valuable if they help to identify issues that move candidate favorability ratings or the best language to frame a given message. Despite the challenges, the economic value of survey data appears undiminished and indeed may have grown as candidates look to reduce the uncertainty of the electoral process and as journalists and political analysts look to provide a contextual understanding of the campaign process.

The result of this economic context is a proliferation in polling but wide variance in the quality of the work. Given this situation, it should come as little surprise that professional organizations (e.g., the American Association of Public Opinion Research) are placing a renewed emphasis on standards—or that blogs and Web sites, such as Pollster.com, have arisen as watchdogs over polling practices and to help provide a better contextual understanding of poll results.

Yet for all the important work being done to assure the credibility of poll results, the question remains whether it is enough. Is the very best polling—with sophisticated sampling strategies and nuanced and careful data analysis—sufficient to capture the meaning of public opinion in a digital age? Or do we need to rethink the meaning of public opinion in contemporary politics? Inherent in these questions is the idea that the meaning of public opinion and its role in American politics have changed over time. In providing an answer, we assume public opinion does (and should) matter in democratic governance but leave open questions of how public opinion is expressed and how, when, and to what effect public opinion is recognized and acted upon by policymakers.

Political Context and the Meaning of Public Opinion

To James Madison, public opinion was indispensable to a republican form of government but would cause great harm to individual rights and liberties if left unchecked. “Had every Athenian been a Socrates,” Madison writes in The Federalist Papers No. 55, “every Athenian assembly would still have been a mob.” The institutional framework crafted by the U.S. Constitution is a testament to Madison’s concerns about the potentially adverse consequences of government by the people.

The larger contours of American political history have witnessed the expansion of “the public” to groups originally excluded from political participation (poor white males, African Americans, and women) and the opening of channels for greater direct public influence over elected officials (e.g., the direct election of U.S. senators established by the Seventeenth Amendment and the adoption of direct primaries). As the definition of the public expanded and channels for public influence increased, the expression of public opinion narrowed to focus first on counting votes and then on the expression of privately held opinions as measured through the public opinion poll.

Over time, the primary tool for gauging public opinion—the public opinion poll—became synonymous with the definition of public opinio...