![]()

1

THE GALVESTON HURRICANE OF 1900

On the morning of Saturday, September 8, 1900, some residents of the seaside city of Galveston, Texas, flocked to the beach to watch the very large waves and surf that were crashing on the beaches. For late summer there was an unusually brisk wind from the north. The Weather Bureau had warned residents of an oncoming coastal storm, but there were no official Weather Bureau reports of a hurricane over the Gulf. Many of these residents had experienced mostly nondestructive coastal storms in recent decades, and apparently expectations were for just another storm that would break the late-summer doldrums and provide a bit of excitement and entertainment at the beaches. Just a few hours later, however, Galveston was devastated by a major hurricane with a record storm surge that flooded and destroyed much of the city, resulting in the greatest loss of life during any American natural disaster to the present day.

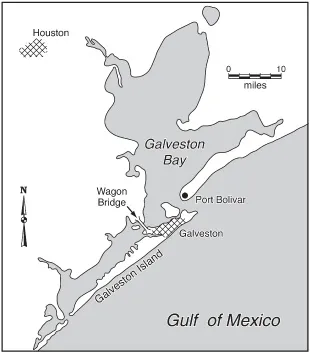

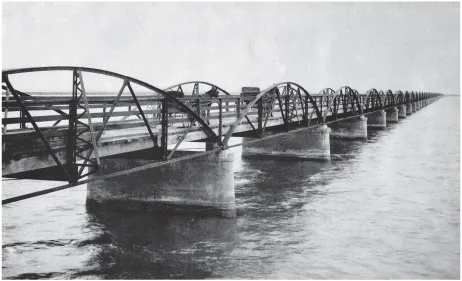

At the turn of the century, Galveston was one of the most important ports of entry in the entire country, rivaling New Orleans on the Gulf Coast. Further growth seemed assured because Texas and the Great Plains to the north were being inundated with new settlers, and commerce and the economy were growing rapidly. However, the city of Galveston was located on a barrier island, thirty miles long, but only two miles wide at most, and separated from the mainland by Galveston Bay, which is three miles wide at its narrowest point (see fig. 1.1). Three railroad viaducts and a single roadway—at the time, a wagon bridge—over the bay connected the city with the mainland, but these transportation arteries were especially vulnerable to closure during stormy weather (see fig. 1.2). Furthermore, the developing city of Houston, located more than forty miles inland, but with plans for an oceangoing ship canal connecting Houston with the Gulf and new port facilities, was becoming serious competition for Galveston, offering shippers the potential for much more efficiency and safety than at the port of Galveston.

Fig. 1.1. The Galveston area as of 1900 before the hurricane.

Fig. 1.2. This 2.1-mile wooden-plank wagon bridge was said to be the longest roadway bridge in the world when completed in 1893. It connected Galveston with the mainland but, along with three railroad trestles, was destroyed during the hurricane of 1900, making access to Galveston very difficult after the storm.

The highest point on Galveston Island was less than nine feet above the sea. There were bathhouses and pavilions at the beach, with several extending outward on pilings over the surf for more than a hundred feet. Commercial and shipping facilities were located on the mainland side of the island facing Galveston Bay. Larger homes and mansions were mostly on higher ground midway across the island along Broadway. Seeing as the city had easily survived several tropical storm and hurricane strikes in the nineteenth century, the local chief of the Weather Bureau at that time, Isaac Cline, believed that the broad, shallow slope of the Gulf bottom offshore and the extensive marshlands on the inland margins of Galveston Bay helped to make the city less vulnerable to really destructive storm surges. Cline’s belief was contrary to the hurricane surge events in 1875 and 1886 at Indianola, a coastal town 115 miles southwest of Galveston with six thousand residents in 1875. The 1875 storm surge at Indianola destroyed three-quarters of the buildings, and the even higher surge in 1886 destroyed all buildings or rendered them uninhabitable. Indianola was never rebuilt.

In order to follow the development and progress of the storm that overwhelmed Galveston on Saturday, September 8, 1900, we need to understand the organization of the United States Weather Bureau at that time and the technology available for monitoring storms at sea and forecasting their tracks and intensities. The Weather Bureau had originally been administered by the Signal Corps of the United States Army, with a hierarchy similar to the military and absolute authority for all operations and forecasts centralized at headquarters in Washington, D.C. All forecasts of extreme weather events, whether tornadoes, hurricanes, or floods, had to emanate from headquarters and were then transmitted by telegraph lines to local offices such as Galveston’s. Weather Bureau headquarters was reluctant to mention or forecast events that could negatively affect business activity, and the use of the term hurricane was restricted to rare, extremely severe tropical storm systems. In 1891 the Weather Bureau was transferred to the Department of Agriculture, since farmers and ranchers were very interested in obtaining weather reports and forecasts focusing on crop production and environmental conditions. But despite the administrative relocation, the Weather Bureau continued to preserve its military command structure.

In 1900, Cuba was still under the administration of the War Department of the United States, after the conclusion of the Spanish-American War of 1898 and the removal of the Spanish colonial government. The Weather Bureau was not impressed by the Cuban meteorologists at Havana, who had many decades of experience with local forecasts of hurricanes over Cuba and the West Indies and also a strong following among the Cuban population. The Weather Bureau had established a new American Weather Bureau office in Havana, but the Weather Bureau chief in Washington soon became irritated by forecasts published daily by the Cuban meteorologists that conflicted with forecasts issued by headquarters in Washington. In August 1900, in the middle of the hurricane season, the Weather Bureau was successful in preventing cable transmission of all weather information regarding storm warnings by the Cuban meteorologists. Hence, reporting of tropical storms or hurricanes back to headquarters was limited to the very conservative perspectives of tropical storm development by Weather Bureau personnel, and the Cuban expertise was largely ignored.

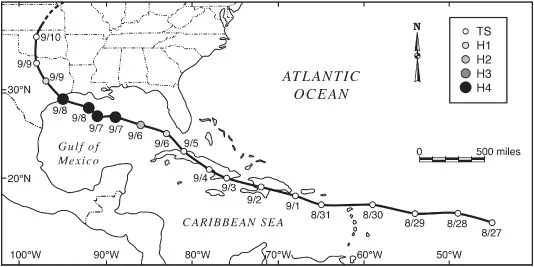

By Friday, August 31, based on island observations entered into the telegraphic network, both American and Cuban meteorologists recognized that a weak tropical storm was moving westward over the Atlantic across the Leeward Islands east of Puerto Rico. The storm remained rather weak and disorganized as it passed over Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, and Haiti but arrived over southeastern Cuba somewhat strengthened on Monday, September 3, when twenty-four inches of rain were recorded at Santiago, Cuba (see fig. 1.3). On Wednesday, September 5, only three days before landfall at Galveston, the tropical storm swept over western Cuba moving from southeast to northwest without serious damage. Cuban meteorologists suspected hurricane status once the storm left Cuba, but Weather Bureau personnel in Cuba continued to report to Washington that the tropical storm was weakly organized.

Fig. 1.3. Storm track and Saffir-Simpson intensity categories of the Galveston Hurricane of 1900 as interpreted by the National Hurricane Center.

The storm strike in Cuba was reported by telegraph to the Weather Bureau in Washington. Forecasters at headquarters anticipated that the storm would follow a traditional track and curve slowly toward the north and then northeast, cross northern Florida, emerge over the Atlantic Ocean, and then track northeastward along the Carolina and Mid-Atlantic Coasts. But real-time weather data around the Gulf and data transmission by teletype to headquarters were limited to the coastal Weather Bureau offices, and it was not possible at that time for real-time transmission of observations from ships at sea on the Gulf. Hence, after the hurricane left Cuba and moved over the southeastern Gulf, there were no observations to pinpoint the precise position of the storm, unlike Hurricane Katrina more than one hundred years later.

On Thursday, September 6, less than three days before landfall in Galveston, the Weather Bureau in Washington continued to alert shipping interests along the East Coast from the Carolinas northward of the possibility of a major storm event. However, there had been no evidence of a storm tracking across the Florida Peninsula from the Gulf to the Atlantic, and observations of brisk northerly winds at coastal Weather Bureau offices along the central Gulf should have suggested that the storm—or cyclone, a term often used for storms of tropical origin—was moving in a northwesterly direction across the central Gulf of Mexico. The Weather Bureau forecasting services in Washington did not order storm predictions or warnings for the Gulf Coast, and local Weather Bureau personnel along the Gulf Coast were not allowed to issue storm or hurricane warnings on their own.

Early on Friday morning, September 7, only about thirty-six hours before landfall, local meteorologist Cline, living only three blocks from the beach, became aware of rising water levels, storm swells from the southeast, and a thunderous surf. Cline recognized that there had to be a significant storm somewhere over the Gulf (see fig. 1.4). The Weather Bureau in Washington finally ordered “storm warnings” along the northern coasts of the Gulf, including Galveston Island, but with no mention of a hurricane threat. The weather on the island remained fair, and residents were mostly unaware of the storm approaching from the southeast. In fact, adults and children flocked to the beach to enjoy the brisk cooler winds from the north and the crashing surf.

Weather Bureau transmissions from Washington had continued to suggest that a storm was moving up the Atlantic Coast, but at 11:30 a.m. another transmission from Washington arrived in Galveston reporting that a “moderate” tropical storm was over the Gulf, south of Louisiana, and moving toward the northwest, threatening the southeastern Texas coast Friday night and Saturday. Cline’s office issued a storm warning, but no hurricane warning, since issue of these warnings was still strictly limited to headquarters in Washington. It should be noted that modern analyses of the storm track and intensities by the National Hurricane Center (see fig. 1.3) indicate that the storm had exploded to category four status with the center only about 150 miles southeast of Galveston by Friday morning, with the outer bands of hurricane-force winds much closer. Later in the afternoon with fair but windy weather, Cline observed that the sea and surf were still rising and beginning to flood the ends of streets at the beach; he sent a concerned telegram to headquarters in Washington that he had never before observed such high water together with brisk offshore winds from the north.

Fig. 1.4. Dr. Isaac Cline, chief of the Weather Bureau office in Galveston during the 1900 hurricane. This photo was taken much later, during his controversial tenure in charge of the Weather Bureau Center for the Gulf Coast in New Orleans (1901–1935).

At dawn, Saturday, September 8, the surf was even higher. Rising water from Galveston Bay, driven by the brisk northerly winds, was beginning to flood streets and wharves along the commercial waterfront there. But most city officials and the public, including Cline and the other Weather Bureau personnel, anticipated a day of stormy weather but nothing that had not been experienced before. They had no clue that they were about to experience a major hurricane strike that very afternoon. For much of the early morning, families walked or rode streetcars to the beach to watch the spectacular fountains of surf against the bathhouses and piers.

By noon, however, driving rain, rising Gulf water levels, and mountainous waves began crashing into the bathhouses and stores at the beach. The streetcars stopped operating, and the crowds at the beach were now desperately trying to make their way through the rising water and increasing winds toward Broadway and the substantial buildings along the highest ground on the island. It soon became difficult to wade through the seawater, which was laden with debris and flowing rapidly more or less from east to west, nearly parallel with the beaches. At the same time, screaming winds from the north were beginning to tear apart roofing, with shingles and slate becoming death-dealing missiles. The island was being flooded both from the Gulf, due to the rising storm surge and high waves, and from Galveston Bay, because of gale- and hurricane-force winds from the north.

The last train to arrive in G...