![]()

Part 1

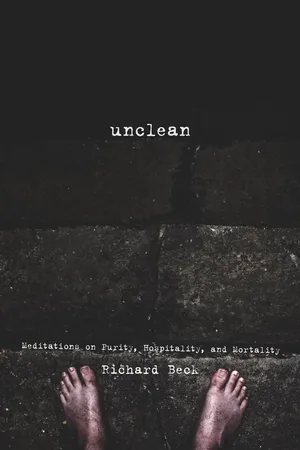

Unclean

Humans are most likely the only species that experiences disgust, and we seem to be the only one capable of loathing its own species.

—William Miller, The Anatomy of Disgust

![]()

1

Darwin and Disgust

The term “disgust” in its simplest sense, means something offensive to the taste. It is curious how readily this feeling is excited by anything unusual in the appearance, odour, or nature of our food. In Tierra del Fuego a native touched with his finger some cold preserved meat which I was eating at our bivouac, and plainly showed utter disgust at its softness; whilst I felt utter disgust at my food being touched by a naked savage, though his hands did not appear dirty. A smear of soup on a man’s beard looks disgusting, though there is of course nothing disgusting in the soup itself. I presume that this follows from the strong association in our minds between the sight of food, however circumstanced, and the idea of eating it.

—Charles Darwin, Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals

1.

Disgust is a surprising emotion. It is startling how many aspects of daily existence are affected by this emotion. In the morning I rise, brush my teeth, shower, and apply deodorant. I don’t want to smell bad to others. I don clean clothing and will worry later if my fly is down during my lectures. I eat with my mouth closed. I avoid creepy people in public places. I wrinkle my nose at the food left too long in the fridge. I spray air freshener in the workplace bathroom after I’m done. I feel revulsion at the crime I hear about on TV. I am repulsed by how much blood was in the R-rated movie. I tell my son to apologize for farting or burping at the dinner table. I worry about shaking hands after my coworker sneezed into his own. I kiss my wife on the mouth but am revolted at the prospect of greeting others this way. I watch a person get baptized with water at my church. I sing songs about being “washed in the blood of the Lamb.” I struggle with my not-so-clean conscience. I chase the bug my wife saw in the bathroom. I send my soup back because I found a hair in it. I read about a genocide, an act of ethnic cleansing.

From dawn to dusk, disgust regulates much of our lives: biologically, socially, morally, and religiously.

The varieties of disgust are built atop a common psychological foundation. Consequently, to understand how disgust affects us, how it can regulate aspects of our social or moral lives, it will be necessary to understand the basic psychology of the disgust response. Having a firm grasp of the psychological fundamentals of disgust will be important, and illuminating, as we go forward.

Charles Darwin is often credited with initiating the modern study of disgust in his book Expressions of the Emotions in Man and Animals. Expressions is now recognized as a seminal work in the field of evolutionary psychology. In Expressions Darwin documented facial, physiological, and behavioral similarities between humans and animals when we experience basic emotional states. For example, both dogs and humans expose their teeth when angry. Chimps and humans both grin when anxious. Our hair stands on end, like cats, when we are scared.

Darwin devotes a chapter in Expressions to the emotion of disgust. As seen in the quote at the start of this chapter Darwin links disgust with food and the prospect of eating something that has come into contact with a polluting influence, like the touch of a “naked savage.” Darwin also notes that disgust is characterized by a distinctive facial response seen in the wrinkling of the nose and the raising of the upper lip. Due to the work of the psychologist Paul Ekman we know that this distinctive facial expression is a cultural universal. All humans make the same face when experiencing disgust. Disgust, it appears, is an innate feature of a shared and universal human psychology.

The distinctive movements of the mouth, eyes, and nose involved in the facial expression of disgust are due to a constriction in the levator labii muscle region of the face. This constriction is characteristic of an oral/nasal response to reject something offensive that has been eaten. Linked to this response is the impulse to spit. As Darwin notes, “spitting obviously represents the rejection of anything offensive from the mouth.” Finally, if swallowed, the experience of nausea promotes vomiting, forcefully expelling the offensive object from the body.

At its root, then, disgust is found to be involved in monitoring oral incorporation (mainly eating) and keeping track of food aversions. The psychologist Paul Rozin calls this core disgust. Basically, core disgust monitors what we put in our mouth. Core disgust is an innate adaptive response that rejects and expels offensive or toxic food from either being eaten or swallowed.

We have only just begun our survey of disgust psychology and already two important observations have been made. First, disgust is a boundary psychology. Disgust monitors the borders of the body, particularly the openings of the body, with the aim of preventing something dangerous from entering. This is why, as seen in Matthew 9, disgust (the psychology beneath notions of purity and defilement) often regulates how we think about social borders and barriers. Disgust is ideally suited, from a psychological stance, to mark and monitor interpersonal boundaries. Similar to core disgust, social disgust is triggered when the “unclean,” sociologically speaking, crosses a boundary and comes into contact with a group identified as “clean.” Further, as we will see in Part 2 of this book, the boundary-monitoring function of disgust is also ideally suited to guard the border between the holy and the profane. Following the grooves of core disgust, we experience feelings of revulsion and degradation when the profane crosses a boundary and comes into contact with the holy.

Beyond functioning as a boundary psychology we have also noted that disgust is an expulsive psychology. Not only does disgust create and monitor boundaries, disgust also motivates physical and behavioral responses aimed at pushing away, avoiding, or forcefully expelling an offensive object. We avoid the object. Shove the object away. Spit it out. Vomit.

This expulsive aspect of disgust is also worrisome. Whenever disgust regulates our experience of holiness or purity we will find this expulsive element. The clearest biblical example of this is the scapegoating ritual in the Hebrew observance of the Day of Atonement (cf. Leviticus 16), where a goat carrying the sins of the tribe is expelled into the desert. The scapegoat is, to use the language of disgust, spit or vomited out, forcefully expelling the sins of the people. In this, the Day of Atonement, as a purification ritual, precisely follows the logic of disgust. The scapegoating ritual “makes sense” as it is built atop an innate and shared psychology. The expulsive aspect of the ritual would be nonsensical, to either ancient or modern cultures, if disgust were not regulating how we reason about purity and “cleansing.”

The worry, obviously, comes when people are the objects of expulsion, when social groups (religious or political) seek “purity” by purging themselves through social scapegoating. This dynamic—purity via expulsion—goes to the heart of the problem in Matthew 9. The Pharisees attain their purity through an expulsive mechanism: expelling “tax collectors and sinners” from the life of Israel. Jesus rejects this form of “holiness.” Jesus, citing mercy as his rule, refuses ...