![]()

1

Introduction

Remembering Our History, and Forging

Stories of a Hopeful Future

“Mudzimu weshiri uri mudendere.”

(“The ancestry, roots, and survival of a bird are in its nest.”)

—Shona proverb

“Usakanganwe chezuro ngehope” literally translates from Shona to mean, “Do not forget yesterday’s experiences because of a good night’s sleep.” Even in situations where one experiences a bad night, one does not forget other past experiences because of the night experience. A common saying among the Shona is, “When you forget your past, you will never know the truth.” For how can we know where we are going if we don’t know where we’ve come from or where we are presently located? When one loses the memories of one’s past, one is most likely to lose one’s present grounding, and ultimately one’s place of embeddedness in the future as well.

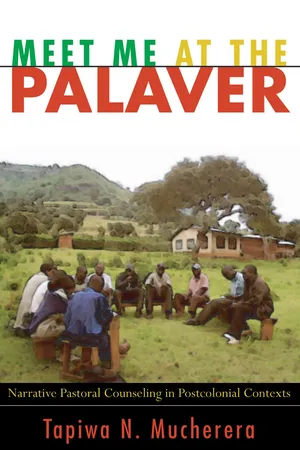

History is a contextual story. People create history out of stories rooted in their ancestry. Past stories, when weaved together with narratives from modern indigenous communities, contribute to the constructing or forming of both individual and communal identities. This chapter serves both as an introduction to the accounts of a common encounter of the indigenous peoples (colonization and Christianity) and as an introduction to the whole book (how the past and the present narratives of indigenous Africans can be woven together to create a hopeful future using narrative pastoral counseling). This book is about how narrative pastoral counseling—or how stories (personal, family, community, folk, biblical)—can be used in pastoral care and counseling to restore hope in contemporary indigenous communities such as Zimbabwe, despite stories of subjugation from the past, and in light of the present context of the HIV and AIDS pandemic, poverty, and other problems. The palaver (pachiara, padare), a traditional narrative-counseling approach common in many traditional indigenous settings and still present in many African contexts, will also be explored for how it could be reintroduced in most of today’s African contexts. As much as this book focuses on Africa, and more specifically on the Shona of Zimbabwe, the material it covers can be easily generalized to many of the indigenous contexts that experienced colonialism and who are faced with poverty and the HIV/AIDS pandemic. In order to understand the indigenous people’s story, one cannot ignore a people’s past historical experiences, since these still have great impact on the people today. Thus this book presents their struggles, and in the last chapters closes with how hope can be restored in such contexts as Zimbabwe. Finally, the work of African churches and communities will be highlighted—these beacons bringing hope to the grim context of poverty and the HIV/AIDS pandemic.

Indigenous People: A History in Synopsis

The contexts and life narratives of indigenous peoples have been a “mixed bag,” given that indigenous people have been viewed both as blessed and as the “wretched of the earth” due to imperialism. They are blessed in that these contexts have persevered and preserved a rich source of humanity’s traditional religiocultural values. Still today anthropologists study these communities to understand the origins of humanity’s traditional wisdom and ways of life. In most of these contexts where there was and is less “invasion,” they are still rich in natural resources and uncharted lands.

One of the root causes of the “wretchedness” of indigenous peoples came by way of subjugation through colonial imperialism. These stories are filled with pain and suffering. Today suffering continues under neocolonial governments, unjust economic structures (locally and globally), and the pandemic diseases, such as HIV and AIDS. However, these experiences of pain and suffering have not totally eroded the hope for a better future.

Survival is the dominant story one hears even in these desperate situations. As the old adage states, “In times of drought, the survival of a tree is in the depth of its roots.” History has taught indigenous people that there is always hope if they are rooted in God and remember that God always raises a “stump, the holy seed” (Isa 6:13). In these difficult situations, stories from precolonial and colonial times are shared, reminding the younger generation not to focus only on the painful neocolonial present, but to also imagine what the future would and will look like. Even under this inescapable net of neocolonialism, hope is found as indigenous people groups seek to remember the story of who they are as a people, and as they focus on alternative possibilities to the present story.

Much change has taken place in the religiocultural and psychological worldview of neocolonial indigenous nations, and more specifically in Africa, since the advent of Christianity and colonialism. Three different layers of stories exist in the African context: the precolonial or traditional, the colonial, and the post- or neocolonial stories. All three levels are important in addressing situations of narrative pastoral crisis intervention or counseling. The stories of precolonial or traditional times still form some of the foundations and are highly influential for indigenous people around the world. As much as the histories of most indigenous people were passed down orally, one cannot ignore this part of their story and expect to fully understand them.

The arrival of the colonialists marked the start of written history, since in these contexts history was passed down orally. Colonial history writers did not bother to include the oral history of the indigenous peoples. Written history, therefore, in most indigenous contexts was written or presented to the exclusion of precolonial eras. Some Westerners regard the stories of the indigenous people as an unnecessary inconvenience. It is as if they are saying, “If we could just rid them of their precolonial history and educate all the indigenous people to a Western way of life, then this world would be a better place.” A joke is usually shared about a colonizer who said: “Our country [the colonized country] would be a better place without you natives.” The colonizers forgot they were the foreigners. Besides distorting historical facts, another violation the colonists committed was taking native lands.

The Subjugation of Natives’ Land through Violence

From indigenous people colonizers stole land—one of the greatest resources, which native peoples held dear. The natives did not believe in owning the land, but instead saw it as a gift from the Creator. The land was guarded by the “living dead,” or ancestors, in order to feed the living. Of the Shona belief about the land Bourdillon says:

The earth is not “dirt” as it is referred to in the West, but was and still is the source of life. It is a generally held belief by most indigenous peoples that they were created out of “mother earth—the soil,” and from her they receive nourishment, livelihood, and their sustenance. When colonizers came, they did not live by these same values. Land, and all that was on it, was to be subdued and plundered for personal gain. The colonizers took the hospitality of the natives as stupidity. Musa W. Dube, a professor at the University of Botswana, relates the common story that she quotes from Mofokeng’s article on how the Africans lost their land in exchange for the Bible. Dube writes: