eBook - ePub

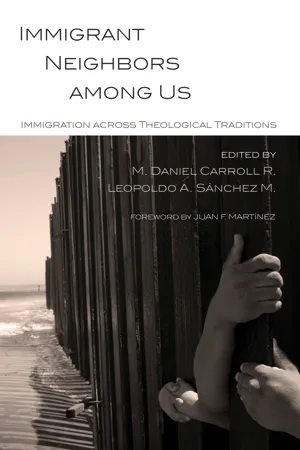

Immigrant Neighbors among Us

Immigration across Theological Traditions

This is a test

- 162 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Immigrant Neighbors among Us

Immigration across Theological Traditions

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

How do different Christian denominations in the United States approach immigration issues? In Immigrant Neighbors among Us, U.S. Hispanic scholars creatively mine the resources of their theological traditions to reflect on one of the most controversial issues of our day. Representative theologians from Roman Catholic, Lutheran, Reformed, Methodist/Wesleyan, Pentecostal, and Independent Evangelical church families show how biblical narratives, historical events, systematic frameworks, ethical principles, and models of ministry shape their traditions' perspectives on immigrant neighbors, law, and reform. Each chapter provides questions for dialogue.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Immigrant Neighbors among Us by M. Daniel Carroll R., Leopoldo A. Sánchez, Carroll R., Sánchez M. in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Church. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

Christian Church1

A “Documented” Response1

Papal Teaching and People on the Move

In 1965, the last of the documents promulgated by the Second Vatican Council began with the stirring words, “The joys and the hopes, the griefs and the anxieties of the men [sic] of this age, especially those who are poor or in any way afflicted, these are the joys and hopes, the griefs and anxieties of the followers of Christ.”2 With this turn to the “signs of the times” and the obligation to scrutinize them critically in light of the Gospel, the Council situated the Roman Catholic Church firmly within the world. Today, set against the backdrop of unprecedented global migrations, Catholic communities across the globe and within the United States of America seek to understand themselves in terms of the world in the local church. Consider this example from Malaysia, a prominent migrant-receiving country. On a 2011 visit to St. John’s Cathedral in Kuala Lumpur for Mass, Filipina theologian Gemma Tulud Cruz observed:

. . . the diversity of the church goers was striking. Beside the local Catholics who were Indians and Chinese, there were Westerners as well as Asians and Africans from various countries . . . in that huge cathedral overflowing with people of various colors from various parts of the world, one gets a sense of the world church and a glimpse of what is probably the future of the church, that is an intercultural church brought about or, at the very least, reinforced by migration.3

Peoples in motion, many escaping poverty, lack of opportunity, civil strife, the aftermath of natural disasters, and/or oppression bring the world into the local church, across neighborhoods and barrios, in concrete ways. Marcelo M. Suárez-Orozco suggests that the phenomenon of globalization has created “homo sapiens mobilis.” If all contemporary emigrants and immigrants were considered together they would comprise what he calls “Migration Nation,” an entity third only to China and India in population.4

Concern by the Roman Catholic Church for people on the move is not only reserved for this most recent trend; it has been articulated across time in any number of venues especially from the highest levels of pastoral leadership.5 This chapter will focus on the “documented” legacy of this Christian denomination and pay particular attention to the contributions of the pontificates of Pius XII (1939–1958) and Paul VI (1963–1978), followed by John Paul II (1978–2005), Benedict XVI (2005–2013), and Francis (2013–), three Bishops of Rome who themselves emigrate in order to fulfill the responsibilities of the office entrusted to them as “servants of the servants of God.” It will conclude with an assessment—done latinamente—of key theological contributions and pastoral trajectories that this extensive body of documented teaching offers to ongoing public, ecumenical, and interreligious conversations on migration.

This overview is not from the grassroots but from the side of the magisterium, the teaching authority of the Roman Catholic Church. This survey is not exhaustive but focuses exclusively on select key papal teachings, a textual heritage that is evolving, rich, and documented. The use of the term “documented” with respect to the Church’s teaching regarding people on the move is intentional. Catholics, among others, are often unaware of the substantial corpus of teaching on migration and itinerancy that has and continues to emanate from the Vatican across several centuries. Ignorance of these teachings makes it easier to dismiss the challenging positions taken more recently by local bishops and national bishops’ conferences as meddling in political affairs or as reflections of so-called “liberal” agendas. Highlighting directives from the Vatican on migration matters is necessary, because there is an historical pattern of U.S. bishops failing to respond with pastoral urgency to matters of justice like slavery, racism, and desegregation.6 Furthermore, these teachings and actions first emerged during pontificates most influenced by emigration from Europe toward las Américas in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. U.S. Catholics tend to forget that there are many among us with ancestors, who arrived in these prior waves of immigration and were the objects of international pastoral concern. Finally, Catholicism is a denomination with a globally visible and central public figure that is both Bishop of Rome and head of state.7 The Holy See functions as a sovereign entity with regard to matters of international relations, yet its diplomatic representatives and their activities are oriented toward the protection of human dignity and the common good rather than toward narrowly partisan political ends. In his 1963 radio message commemorating World Migration Day, Pope Paul VI reminded listeners of the tools at the Church’s disposal to mitigate the trials of this global phenomenon: charitable assistance, diplomatic interventions, and the Church’s teaching.8

Teaching Migration: Before and After Vatican II

Concerns for people on the move and the rights and responsibilities of people in sending and receiving nations have been articulated in a trail of documentation that can be traced from Leo XIII through Francis. The teachings are communicated in a variety of formats, including but not limited to papal messages on the annual occasion of the World Day of Migrants and Refugees, apostolic constitutions, exhortations, letters, encyclicals, homilies, and documents from the Second Vatican Council.9 These teachings were all formed in global contexts of several waves of human displacement and mobility.

Historically, the response of the Church to issues of people on the move has been framed with an impetus to pastoral action, attention to ecclesial juridical matters, and theological roots. Several key documents serve as classic examples of this framework: Exsul Familia Nazarethana, the 1952 encyclical of Pope Pius XII; De Pastorali Migratorum Cura, the 1969 Instruction from Sacred Congregation for Bishops, approved and authorized by Paul VI; and Erga migrantes caritas Christi, the 2004 instruction from the Pontifical Council for the Pastoral Care of Migrants and Itinerant People, approved and authorized by John Paul II.10

Pius XII (1939–1958) and Exsul Familia Nazarethana (1952)

The massive displacement of people during and in the aftermath of World War II insured that migration was a matter of concern in the papacy of Pius XII. In 1952 he issued Exsul Familia Nazarethana (EFN), named for the “émigré Holy Family of Nazareth, fleeing into Egypt,” which he affirmed as “the archetype of every refugee family.”11 The first half of this Apostolic Constitution contained a retrospective of what had been done in the past by the Church for the spiritual care of “pilgrims, aliens, exiles and migrants of every kind” (EFN, Title 1). Among the purposes for his wide-ranging account of examples of religious, moral, and social aid was the hope that the “universal and benevolent activity of the Church . . . might thus become better appreciated” (EFN, Title 1). Pius XII was motivated to trace this trajectory with specificity, in particular the contributions of his own pontificate, because he was disturbed by what he perceived as the Church being “unjustly assailed by her enemies and scorned and overlooked, even in the very field of charity where she was first to break ground and often the only to continue its cultivation” (EFN, Title 1).

The survey recapped a wealth of initiatives, especially those enacted by Pius XII himself and his immediate four papal predecessors, beginning with Leo XIII (1878–1903). He copiously cited endeavors focused on providing for the spiritual, sacramental, and even material needs of Catholics on the move. Among others, he included the founding of religious orders to serve and/or accompany migrants at various stages of their journey—points of departure, en route, and in resettlement; the establishment of seminaries to train clergy specifically for the apostolate to migrants; and the creation of national parishes to provide ministry “by priests of their own nationality or at least who speak their language” (EFN, Title 1). His inventory of actions on behalf ...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Contributors

- Foreword

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: A “Documented” Response

- Chapter 2: Who Is My Neighbor?

- Chapter 3: Calvin’s Legacy of Compassion

- Chapter 4: Immigration in the U.S. and Wesleyan Methodology

- Chapter 5: Pentecostal Politics or Power

- Chapter 6: Towards an Hispanic Biblical Theology of Immigration

- Appendix

- Glossary

- Bibliography