![]()

1

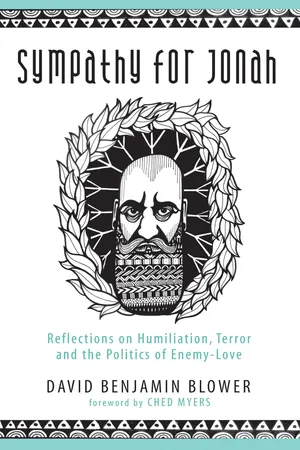

The Whale

On my first encounter with Jonah’s hell ~ On the ubiquity of the myth ~ On the image as a psychological archetype ~ On the monster as providence and grace ~ On rebirth ~ On the necessity of humility to understand humiliation and the necessity of humiliation to precede revolution

I have, at the time of writing, performed just a few scrappy run-throughs of our musical retelling of the Book of Jonah, in a few lounges and to a handful of friends. Some have commented that the whale doesn’t play as big a part as might be expected. For most of us the whale is probably the story’s second character, if not the first. And for myself, like almost everybody else, it was Jonah’s encounter with the whale, or rather the “great fish,” that first pulled me into the story.

It happened one summer’s night that I was to play a local bar. But I was in strange moods at the time, one of the milder symptoms being that I was sick of my own music and wanting to play something else. Michael, who plays the accordion, suggested playing a set of sea shanties and it seemed good to me. Among other things we played a song by The Decemberists about a showdown between two enemies who find themselves face to face having been swallowed by the same whale. And of course we played the lord of all existential sea shanties “Starving in the Belly of a Whale” by Tom Waits. We also had readings from Moby Dick about the murderous albino whale, and from the second chapter of the Book of Jonah which recounts the prophet’s prayer from the belly of the whale. There are songs and tales of the sea that do not involve whale ingestion but it seems we were only drawn to those that did.

Being of fragile mind at the time, I found reading Jonah’s prayer from inside the fish, all set to Michael’s miserable squeeze-box dirge, crushing, horrible and unbearable. The imagery of being thrown into a raging ocean—which rages for you and you alone—and sinking down to a cold, dark, wet, airless death, away from all human pity, drowning in your own fault, only then to encounter the gaping mouth of some unknowable monster with vacant eyes approaching from the black salt oblivion; this is a meditation that falls beneath nihilistic terror. The words which follow from Jonah’s prayer are as vividly hellish as children’s nightmares. I felt my innards turn cold and hard as they sometimes did in that strange season, swallowed alive by this psalm of doom.

Then we played “Troublesome Waters” by Johnny Cash which has no whales in it, and I began to recover myself. What is it about the extraordinary thought of being swallowed by a whale that seems so awful and yet so tangible to the imagination?

The Book of Jonah is very short. It takes up less than two pages of any Bible. But still everybody knows who Jonah is. A lot of pious Christians can’t tell you anything about Amos or Haggai or Micah or Ezekiel, but even if you ask the secularites about Jonah, most of them will tell you, he’s the man who was swallowed by a whale, just as he is known in Islam as “the man of the fish.” This short and bizarre tale at the back end of the Hebrew Bible has become ubiquitous legend, filed away in everybody’s mind. It’s probably true that most of us have not got much idea what the book is actually about. The fact that it’s a recognizable myth, even in the days of secular disenchantment, I should think lies simply in the incredible power of that image: the person swallowed by a whale.

Let’s imagine the story of Jonah goes like this: God tells the prophet to go to Nineveh but the prophet takes flight instead, joining a Bedouin tribe as they head south. After many days the whole tribe has caught some terrible illness and divined that Jonah is the cause of their misfortune. They agree with much reluctance—for they have grown fond of the prophet—to expel him into the desert where he faces a sandy death. Then, unexpectedly, the wandering and dying Jonah is hoisted onto the back of an African elephant (who is lost) and carried the three days elephant-march back to where he had begun; and there God reiterates his commission to the prophet, and so on. The plot is the same, but would the story hold such mythical power if it happened this way? Would we all know who Jonah was, or would he have been as obscure to most of us as Balaam and his talking ass or Elisha, who calls the wrath of an angry bear to his aid? Why must it be a whale to stick in the mind?

Perhaps it has something to do with the mysterious structures of the mind. “How else,” wrote Carl Jung,

Can anyone who is not entirely insensible to the chaos under the floorboards of their own mind escape the psychological metaphor of the ocean surface as the boundary that divides the known world from the unknown, where wild things swim past our feet in the murky depths, terrifying not because we can see them but because we can’t? Perhaps we feel we know something of Jonah’s whale because we sense in it some resonance with our own forgotten nightmares, formless thoughts, and the unresolved troubles that glide darkly beneath us.

It would of course be ridiculous and typical of the present age to talk about the Book of Jonah as though it were written as a sort of psychological exploration of this kind. I hope it will be understood that I’m not wanting to make suggestions here regarding what the Book of Jonah is about (not yet anyway), but I do think perhaps Jonah’s whale casts its own gloomy light on what we human beings are about. Why is the image of a man on his knees in the belly of a whale so compelling to us? The imagery seems to sit in our collective mind precisely because it gives us an archetypal image that resounds with the inner experiences of the human being. I will dare to hope that its psychological resonance might in the end help us to understand what the Book of Jonah really is about, and illuminate the meaning of its terrible call. But we may at least start with the fact that this is, after all, a book about a man who runs from his issues and ends up confronting them on his knees in the warm, wet hell of the monster’s belly. He undergoes a night sea journey, a dark night of the soul. And it is thought by some that all of us must either embark on such a journey and be changed by it, or else barricade our entire lives against its cruel interruption.

So for these sorts of reasons our reflections begin not with chapter one of the book, but chapter two, in the darkness and chaos where,

I doubt that any deeper dungeon has been described outside of Dante’s hell, but it is the utter loneliness of the image that turns the blood cold. At least The Inferno received visitors. When thinking too hard on Jonah’s descent I find my sorry way back to a boyhood fear of being buried alive, or of being lost to some hateful nothingness that has no end. The image isn’t nihilistic. The terror of it lies in his having been willfully discarded into it, abandoned to it, by the hand of his maker; in slipping through the cracks of love into oblivion: “Thou hadst cast me into the deep, in the midst of the seas: and the floods compassed me about; all thy billows and thy waves passed over me.”

And what to make of the great fish? The image by itself carries with it a sense of fatedness, of doom or inevitability; as though the monster had been swimming around looking for Jonah all of its cold, gray life. But the beast which Jonah calls “hell” is not described by the narrator in the language of judgment, but of providence and grace; the grace that comes in the form of unspeakable terror, if we dare believe in such a thing. Once past the teeth and through the gullet, perhaps many of us might even feel a sort of warming solace about that dark belly which God had “prepared” for him under those hospitably arched ribs. Such is the hopeful glow that Pinocchio discovers when he finds, deep in the shark’s belly, his maker Old Joe bleached white and sat at a rotten old table burning the last candle from some swallowed shipwreck. In this melancholy meeting the wooden boy finally lets spill the whole tale of his trials and woes. And it is in the sea monster’s innards that Baron Münchhausen is reunited with the old comrades who will help him to fulfill his future purpose. Somehow many have sensed a certain warmth toward the strange monster that rescues Jonah from the chaos of the sea and holds him in against the storm and carries him like a child in the comfort of irresponsibility. Here, when all vexatious choices and courses of action are out of reach, one can make peace with even a bad situation. The whale’s belly creates the space where Jonah’s flight from God—which is also his flight from himself—ends. Here is the safe place to collapse, to give up and to allow one’s inner structures, defenses, boundaries and coping strategies to be relaxed, or even demolished, so that some new thought can be thought. It is the cave of melancholy council and the awful darkness where unexpected newness can begin. Here Jonah can pray. Here and here only, in hellish gloom, can Jonah speak of hopeful things: