![]()

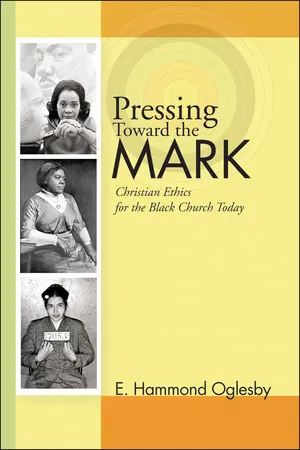

Chapter One

Christian Ethics Roots of the Black Church

In every human breast God has implanted a principle which we call love of freedom; it is impatient of oppression, and pants for deliverance; and by the leave of our modern Egyptians, I will assert that the same principle lives in us.

—Phillis Wheatley, 1753?–1784, Poet

Freedom is a state of mind: a spiritual unchoking of the wells of human power and super-human love.

—W. E. B. DuBois, 1868–1963, Intellectual and Activist

Ethical Principles in Black Church Tradition

Christian ethics in the black church tradition begins with a love of Jesus as Liberator and Provider. Basic Christian ethics in the black church tradition starts with Jesus’ own revolutionary words of the love of God and neighbor. Jesus, as a Jew, made it clear for all who dared to listen that the attitude of love is for all nations, all seasons, and moral traditions. As Liberator and Provider, Jesus made it crystal clear the sorts of things which are morally binding upon all humanity. For example, the New Testament ethical ethos called it the “dual commandment.” Accordingly, a Sadducee lawyer asked Jesus a question—trying obviously to test and entrap him—and he gave the perfect answer for all humanity to ponder:

A vital presupposition of this ethical command is to remember that the attitude of love reflects the highest good for every individual, every interpersonal relationship, every family, every church community, and every nation in our global society. As humans, regardless of what race, creed, color, class, gender or sexual orientation, we are never obligated not to love. Jesus as Liberator and Provider, at every point in his own public ministry, demonstrated the importance of love for one another. Jesus as Liberator and Provider reminds us that love covers your back in good times as well as in bad. We are commanded, therefore, to reach out and love the other not only because “God is love” (1 John 4:16), but because the love of God itself will rise up inside of you and cast out the blindness in regard to my neighbor’s or my brother’s good. As Holy Scripture affirms: “And this commandment we have from him, that he who loves God should love his brother also” (1 John 4:21). For Jesus, our Liberator and Provider, the attitude of love is imperative not only for our own sanity—seemingly in a society gone mad—but also for the neighbor’s good.

Furthermore, Christian ethics in the black church tradition affirms an understanding of the love of Jesus as Liberator and Provider, because the message of the gospel is the ground upon which we walk. As one faithful mother would often say (as I remember growing up as a child in the St. James Missionary Baptist Church of Earle, Arkansas) that “Jesus is my all and all . . . I can go to Him in prayer . . . for He knows my every care!” The love of Jesus as Liberator and Provider is the “true vine” that produces much fruit in the hearts, souls, and minds of people living in our troubled world (John 15:1–5). The love of Jesus is like the gentle eagle that stirs the nest, in order for the little ones to begin to fly, but under the ever-protective wings of the mother eagle. The love of Jesus as Liberator and Provider is like the deep roots of an old oak tree. Here I suspect, metaphorically, that when the storms of life come and forcefully beat upon the tree in a violent way, it may bend but it will not break the old oak tree because its roots are firmly anchored in the soil of God’s mercy and righteousness. To be sure, Jesus gives to the downtrodden and hurting ones in our world deliverance from troubles and oppression (Ps 34:1–6).

Thus, the love of Jesus as Liberator and Provider is not about theological speculation concerning some abstract notion of the good and right thing to do. Rather, the moment you meet Jesus as Liberator or Savior, the good and the right come together as a new creation, a new being in Christ. As we encounter Christ, we become new beings—set free from the chains that bind. As brothers and sisters in Christ, listen to the echo of freedom as witnessed in Holy Scripture:

First of all, the motif of the love of freedom has always been a distinguishing characteristic of the black church tradition in America. Theologically, it is no accident that Jesus is perceived as Liberator and Provider in the hearts, souls, and minds of many African American Christians today. The historical circumstances of suffering and oppression put in the hearts of people of African descent a deep yearning for the fruit of freedom. It seems to me that fruit of freedom was implicitly and explicitly manifested in many of the religio-cultural traditions transmitted from Africa to New World societies in Brazil, the Caribbean, and North America.

For example, certain patterns of worship in the black church tradition, particular forms of communal praise, veneration of the ancestors, African-style drumming and dancing, rites of initiation from boyhood to manhood, and the use of sacred emblems as a sign of divine favor all reflect, to some degree, this preoccupation with a love of freedom. In a brilliant way, Albert J. Raboteau points out in his book Slave Religion: The “Invisible Institution” in the Antebellum South, that the iron hands of slavery and brutal oppression did not totally destroy the “moral core” and living African heritage of black people in the New World. Despite the continuing debate among historians, theologians, and religious leaders over the continuity or discontinuity of African religious tradition today, the good news is centered in a common claim of a love of freedom. Here freedom is not only an abstract by-product of the head, rather freedom is a passionate craving of the human heart. In terms of Christian ethics in the black church tradition, the love of freedom is a pivotal root that unlocks the wonders of God’s wisdom and grace in a land where people of color have been victims of disgrace, slavery, and humiliation. Now in the historical circumstances of black suffering, I find it positively amusing how some slaves fought against the myth of black inferiority by simply thinking critically for themselves. Listen to this report and story by former slave “Aunt” Adeline in regard to a love of freedom:

As a follower of Jesus Christ, I strongly believe and affirm the love of freedom as a root value in our struggle to better understand the religio-cultural tradition of the black church in America. Theologically discerned, the love of freedom is a gift of God. God wills freedom for human creation. But it is a freedom bought with a price. Freedom is not free; it always involves personal responsibility as Christians. Too many people today who profess to be “Christian” are bound by the false assumption that we can know God without loving and knowing one another; that we want God without his passion for the poor and marginalized in the world; we want Christ without surrender and obedience; and we want love without sacrifice. The Christian moral life speaks a truth that must be inclusive of all of these elements. Certainly, oppressed slaves who embraced Christian faith knew, deep within, that when God took away their sins, they would find deliverance not simply in Heaven but here on Earth. Accordingly, the noted scholar Professor Eugene D. Genovese, in his classic volume Roll, Jordan, Roll, makes a cogently relevant observation regarding the world of slaves, vis-à-vis Christianity:

In the second place, slaves, as Christians, were drawn to the ethical tenets of biblical faith not only because they held the conviction that “they loved Jesus” but also the realization that “God loves us.” God’s love for us empowers our being in human community. God’s love for us, especially as a people with a shared memory of suffering and oppression, will not return void in the long struggle for freedom, justice, and racial equality in American society. Hence, the ethical principle of “God’s love for us” points us toward the importance of family love. Christian ethics in the black church tradition affirms the crucial value of family ties and family love. There is, undoubtedly, a certain bond in the tapestry of family love that cannot be found in the solitary life of the individual. God loves us as individuals in need of grace—“Yes!” But even more dynamic, God seems to love us in the form of family as the universal expression of a covenant promise (Deut 7:6–9; John 3:16). The enduring symbol between God and the whole created order is covenant-love.

Ethically considered, this principle in the black church tradition means “family love.” Therefore, it is my fundamental belief and observation that family love is a key principle in our struggle to understand the beauty and complexity of the black church tradition. Metaphorically, we can say that “God’s love for us” is the root of the vine, and family love is a blossoming branch of the vine. As family, it is powerful to remember that in the theater of love God always takes the first step toward us. Simple as it is profound, every one of us who believes in Jesus as Liberator and Provider is morally obligated to respond in love to one’s brother or sister. On this point the Bible clearly states: “We love, because He first loved us. If any one says ‘I love God,’ and hates his brother, he is a liar; for he who does not love his brother whom he has seen, cannot love God whom he has not seen” (1 John 4:19–20). Be that as it may, I am convinced in my own heart, mind, and spirit that the principle of “God’s love for us” takes the functional expression—more often than not—of family love in the black church tradition. For example, in his classic book A Black Political Theology, J. Deotis Roberts discusses the fascinating paradigm ujamaa, which is an African concept meaning “family-hood” or “the love of family.” In exploring the boundaries of social struggle in the black church tradition, in light of the radical love revealed in Jesus Christ, Roberts writes:

In the third place, Christian ethics for and in the black church tradition seems to affirm that God favors the poor and marginalized in our world. The drama of God’s unending love and presence with the people of Israel as disclosed in the Exodus story is a testimony to the freeing and unfailing power of the Creator. It seems to me that in the context of the black church tradition, there is a feeling and perception that the Exodus story is our story: that the particular thoughts, actions, images, and sufferings of the ancient Hebrew people are spiritually and emotionally connected to the experiences of slavery, moral degradation, and poverty heaped upon the shoulders of blacks and other people of color in America. Yet in spite of these forms of racial injustice and dehumanization, the God of the Bible still favors the poor, the least, and the last in our global community. If Christian ethics begins with Christian beliefs, then one of those scandalous beliefs is the story of God’s love and presence with the needy and outcast. Therefore, the ethical concern for the poor and “disinherited” in the land is a constant refrain in the black church tradition. God loves us; but I don’t think many of us actually comprehend how radical this love is in the moral struggle for justice in behalf of the poor. For example, in the book of the prophet Isaiah, there are burning “woe...