![]()

1

“Beginning a Society of Their Own”

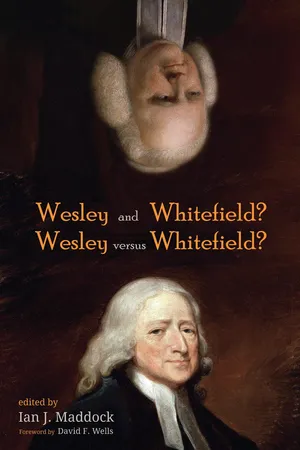

John Wesley, George Whitefield, and the Bristol Division

Joel Houston

Historical analyses of doctrine often run the risk of flattening the concept into a simple ideological notion—doctrine becomes an abstract idea, a proposition to be assented to (or argued with) and little else. Leif Dixon underscored this danger in his work on the rise of predestinarianism in Reformation England:

The articulation of doctrine always occurs within a social nexus. Dixon’s work uncovered much of the underlying psychological dynamics present in predestinarian thinking up until the mid-seventeenth century. This investigation naturally leads to one of the most public predestinarian disputes since the Reformation, untouched by Dixon: the fracture in the evangelical revival between John Wesley and George Whitefield. This acrimonious dispute has come to be known as the “Free Grace” controversy (1739–1744). Dixon’s argument, however, is not a new one and the understanding of the social elements of doctrine is not a novel concept.

A cursory understanding of the social elements of doctrine existed even in the immediate aftermath of the “Free Grace” controversy, exemplified in an anonymous anti-Methodist pamphlet entitled, “A Brief and Impartial Account of the Character and Doctrines of Mr. Whitefield and Mr. Wesley.” The author painted Whitefield in unbecoming terms and argued that he was determined to establish a church “whereof he was to be the head.” John and Charles Wesley were presented in equally unflattering language as men who “had hitherto gone hand in hand with [Whitefield] in everything, but they too perceive[d] that all the glory redounded to him, and that they were only considered as his private followers, began to set up for themselves.” The author of the pamphlet asserted that the key to the establishment of a distinct brand of Wesleyan Methodism was Wesley’s “Arminian” interpretation of the Reformed doctrine of predestination. The anonymous author is worth quoting at length:

The anonymous author’s assessment is instructive: the doctrine of predestination functioned as an instrument to differentiate and identify a distinct socio-religious entity, what would become the Wesleyan Methodist society. This new society existed within the broader ecclesiastical structure of the Church of England yet was “a distinct party” from Whitefield’s Calvinistic Methodists through the preaching of “free grace” (by which the author means unlimited atonement and conditional election).

What follows is an examination of the events leading up to, and including, the “Free Grace” controversy itself. This essay will account for Wesley’s rise to a position of leadership and authority in the early Methodist circles of Bristol and London from 1739 to 1740, superseding the position that Whitefield maintained before his second transatlantic voyage. Employing the insights of McGrath, Dixon, and the anonymous author of the Impartial Account, the present analysis seeks to uncover some of the less commented upon functions of doctrine, most notably, how doctrine functions as a “social demarcator.” This essay will argue that John Wesley used his interpretation of the doctrine of predestination as an instrument to uniquely identify his proto-Methodist societies over and above the supervision that Whitefield had over the early Bristol and London groups. As such, predestinarian conflicts helped galvanize a particular brand of Methodism by imparting a sense of social identification while retaining the broadly orthodox features of a society within the Church of England.

“A Fire Kindled in the Country”: George Whitefield’s Bristol Ministry

Whitefield initiated his immediately successful, if ecclesiastically unorthodox, mini...