![]()

1

‘THIS FESTIVAL OF OURS IS A DEADLY SERIOUS AFFAIR’

By 1945, the year the Second World War ended, the United Kingdom had been ravaged by six years of war. With the explosion of atomic bombs at Nagasaki and Hiroshima, a new threat was unleashed on the world: a war to end all wars. Clement Attlee’s Labour administration entered government that same year, with a fearsome amount to achieve in rebuilding and re-housing Britain, and an ambitious programme for sweeping nationalization of major industries and public utilities that included the Bank of England, coal, gas, electricity, the railways, canals, road haulage and iron and steel, and an aspiration to nationalize the land itself.1

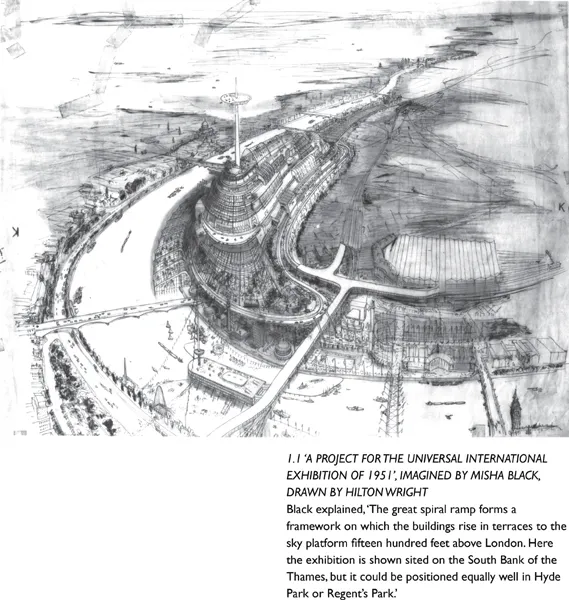

The same year, industrial design consultant John Gloag repeated an idea broached privately a couple of years earlier by the Royal Society of Arts (the organization that encouraged arts, manufactures and commerce and had initiated the Great Exhibition in 1851). In a September letter to The Times, Gloag proposed a centenary be held of the Great Exhibition at Crystal Palace in Hyde Park of 1851. This would, he believed, provide an occasion upon which to boost trade, gain prestige and show off national inventiveness.2 Three days later, Gerald Barry, Editor of Liberal broadsheet News Chronicle, echoed this proposal. In an open letter addressed to the President of the Board of Trade, Sir Stafford Cripps, he urged that the country needed to stimulate British exports through ‘a great Trade and Cultural Exhibition,’ a centenary of 1851. This project, Barry believed, would be ‘an opportunity for the Labour Government to give an imaginative lead to the nation and the Empire’.3 Barry’s enthusiasm for an event in 1951 had been sparked just after war ended when, he recalled, seasoned exhibition designer Misha Black had visited his News Chronicle office ‘with the drawings for a magnificent new Exhibition building which was to be constructed, as it seems to me now, as a kind of interplanetary edifice more or less suspended in the sky’.4 Black’s futuristic exhibition site, drawn by Hilton Wright and later published in The Ambassador magazine, ingeniously anticipated the choice of the South Bank as central site of the 1951 events by several months. Its single structure was based around the framework of a spiral ramp from which the buildings would rise in terraces reaching 1,500 feet, topped by a vertical feature that anticipated the Festival’s Skylon.

Where Barry’s initial letter had addressed the trade advantage of such an event, successive articles published in News Chronicle focused on its potential value for international diplomacy in the face of the developing Cold War. ‘Great Exhibition would assist world unity’ ran a headline quoting London County Council (LCC) Leader Lord Latham, declaring that ‘In view of the terrifying possibilities of the atomic bomb, the common bonds of culture will be the greatest insurance against future war.’5 As the threat of the atomic war became increasingly magnified, from late 1945, the idea of a universal exhibition in 1951 evolved in the pages of News Chronicle.

Responding to Gerald Barry’s open letter in October 1945, Stafford Cripps declared he was in favour of the idea of a major exhibition in 1951 and the Board of Trade would investigate the subject further in a committee under the chairmanship of prominent industrialist Lord Ramsden, its brief ‘to consider the part which Exhibitions and Fairs should play in the promotion of Export Trade in the Post-War Era’. The Ramsden Committee believed fervently in the economic value of major exhibitions. Reporting in 1946, they unequivocally recommended a ‘Universal International Exhibition’ be held in central London in 1951 ‘to demonstrate to the world the recovery of the United Kingdom from the effects of the war in the moral, cultural, spiritual and material fields’, and as a demonstration of international progress. The process of reconstruction should happen on the level of morale-building and cultural and spiritual enrichment, as well in actual rebuilding, with a major exhibition as the perfect showcase for this. As added justification for the expenditure, the Committee recommended, during the same period, notable progress should be made in the provision of public institutions, industrial buildings, dwelling houses and schools.6 This way the impact would be very tangible.

By 1947, the legacy of war continued to take its toll on Britain. Extreme shortages and extraordinary deprivation prevailed and nearly 2 million people were officially out of work. After a horrendous winter at the start of the year British manufacturing virtually ground to a halt. At the same time, industrial action meant coal production was half a million tons short and steel also in short supply, partly due to a scarcity of skilled labour. In spring 1947, heavy flooding had washed away crops, producing the threat of food shortages, and continuing rations in Britain fell well below the wartime average. More serious even than rationing, since it affected Britain’s ability to buy provisions, was the shortage of foreign exchange currency. This was a result of depleted reserves and extensive national borrowing from North America. Loans from the USA and Canada, agreed after the war had ended, which, it had been hoped, would last until recovery could be achieved in 1951, were almost entirely exhausted by 1947. By September the dollar-poor Labour government had virtually no convertible currency, a situation that precipitated an exchange crisis in government, to be repeated soon after, in 1949 and again in 1951.

The British were in no doubt at the end of the Second World War, with conferences at Yalta and Potsdam, then bombings at Nagasaki and Hiroshima, that they needed their own atomic project. Through this they could fight the potential threat emerging as the division between Western democratic, capitalist countries and communist states of the East widened. The British government’s public response started as the development of fissile material that could either be used for nuclear power or for nuclear weapons. But in 1947 Prime Minister Clement Attlee’s Labour administration decided, under a veil of secrecy, to develop an atomic bomb for Britain. That year Attlee also set up his first Cabinet Committee on Subversive Activities. So Britain began in earnest to construct a Cold War state alongside the existing one.

Into the developing context of suspicion and fear, and in close proximity with discussions about the worsening international climate taking place in Whitehall, came the arrangements for this unprecedented nationwide celebration in 1951. Clement Attlee’s administration accepted the recommendations of the Ramsden Committee and Herbert Morrison was put in charge of events, combining positions as Lord President of the Council, Deputy Prime Minister and Leader of the House of Commons. Professing ‘we ought to do something jolly … we need something to give Britain a lift,’ Morrison took a close interest in supporting and promoting centenary celebrations for 1951.7 But despite the government’s professed light-hearted gesture in staging these events, Attlee and Morrison’s interest in marking the centenary focused on its potential instrumental value in improving national morale, boosting trade and in displaying Britain as exemplar democracy to the world. This was an impoverished administration, already under enormous financial strain, and such expenditure had to be justified.

Herbert Morrison formally presented the idea of an event to mark the ‘Centenary of the Great Exhibition of 1851’ to Parliament on 5 December 1947. These events, he announced, would be accompanied by no new building and, in spite of Ramsden’s recommendations for an international exhibition, all would be focused on Britain alone.8 An international trade fair had been ruled out for 1951 as the possibilities of attracting foreign trade were considered limited and, as Morrison later explained to Parliament, shortages of manpower and materials had dictated that Commonwealth governments and administrations could not be invited to take part.9 This British focus also reflected the restricted budget available. Ultimately, it better served the government’s propaganda purpose: Britain’s past achievements and future promise could be shown off to best advantage. MPs raised various concerns: about the use of already restricted materials, the diversion of labour from key building projects, the events’ dubious benefits beyond London, and the danger of Sunday openings; but despite these continuing issues the proposal attracted cross-party support and a pledge of budget. To direct the events a new temporary department – the Festival Office – was set up in Whitehall, the heart of British government.

Gerald Barry (1898–1968) was appointed Director-General in 1947.10 For 11 years editor of News Chronicle, he strongly believed that a new Britain should not only be planned in government, through policy and principle, but that architects and designers had as crucial a part to play by building it in three-dimensions. Before the war he had been a patron for new building in his own right: The Forge House, a cottage which Barry had commissioned English modernist architect F.R.S. Yorke (1906–62) to convert and extend, was an extraordinary convergence of old and new and considered one of Yorke’s ...