![]()

I did not want a ‘banlieue film’ made on a shoestring. I wanted the topic to be treated seriously.1

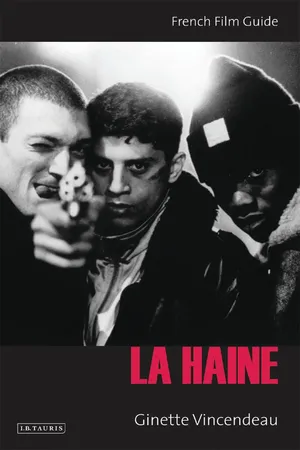

The director: Mathieu Kassovitz

Born on 3 August 1967 in Paris, Mathieu Kassovitz comes from a film background. His mother is the editor Chantal Rémy and his father the television director and occasional actor Peter Kassovitz, who played the shy young man in Jean-Luc Godard’s Vivre sa vie in 1962. His films are mostly made for television, one important exception being Jakob the Liar, 1999, a Jewish ghetto story starring Robin Williams. It is clear that the family milieu fostered a cinephile atmosphere. As Kassovitz is fond of saying, ‘My parents were in film. If they’d been bakers, I would’ve become a baker, but they were film-makers, so I became a film-maker.’2 Young Mathieu was taken to see Stephen Spielberg’s 1971 Duel by his father when he was ten, and at the age of 12 he was making short films in Super-8. As an adolescent he frequented Parisian art cinemas and film clubs, though his taste was for horror, science fiction and ‘the fantastic’,3 and his references were Spielberg and Schwarzenegger rather than Fritz Lang or Renoir.4 He read and produced fanzines about horror films. Nevertheless, he cites Georges Lucas’ nostalgic American Graffiti (1973) – which he says he saw once a week for a whole year5 – and especially Luc Besson’s 1983 science fiction film Le Dernier combat as being particularly influential in determining his desire to make films. Besson’s first feature showed Kassovitz that it was possible to make a genre film cheaply and to make films while still very young. He would in this respect emulate his model, since he was 25 when he made Métisse and 27 at the time of La Haine. The names of Spielberg and Lucas, to whom Martin Scorsese, Brian de Palma and Spike Lee would soon be added, as well as the taste for horror and science fiction (not normally French genres), spell out Kassovitz’s love of American cinema. Although his Americanophilia seems to have been particularly acute (he went as far as to seek out the – then – only McDonald’s restaurant in Paris after his weekly American Graffiti screenings), his tastes are typical of a generation of young men who came of age in the 1980s, when American cinema for the first time outstripped French cinema at the French box office. This was also the time when Kassovitz started taking an interest in hip-hop culture.

Kassovitz’s family background left other important legacies. Peter Kassovitz comes from a Hungarian Jewish family. His own parents were both concentration camp survivors and he himself emigrated after the 1956 coup. Apart from an interest in this history, Mathieu Kassovitz has repeatedly celebrated the Jewish sense of humour he has inherited from his family, and in particular his paternal grandfather, who was a cartoonist; we will see how in Métisse and La Haine Jewishness plays an important part, although in these two films Kassovitz transposes its rituals, idiosyncracies and jokes into a milieu decidedly more working class than his own. Kassovitz has also attributed his social conscience to the left leanings of his parents, whose filmographies bear witness to this.

Kassovitz left school around the age of 17, as he was already more attracted to the cinema, although he did not attend film school. Thus, unlike many of his contemporaries in the jeune cinéma français (young French cinema) trend, he is not an alumni of the FEMIS,1 which may go towards explaining his greater penchant for mainstream cinema, as we will discuss later. Thanks to his father Kassovitz frequented the studios, and he acknowledges the role of this connection6 in helping him obtain his first trainee jobs. From these he graduated to second assistant director on a film by Paul Boujenah (Moitié moitié, 1989), and then first assistant director on industrial films; meanwhile, he began acting in a few movies, including some of his father’s. With FF20,000 he had saved and a borrowed camera he finally made his first short in 1990 (at the age of 23), Fierrot le pou. The title is a pun on the personality of the film’s hero, a geeky basketball player played by himself, and the title of Godard’s Pierrot le fou, although Godard’s relevance seems to stop there. This black and white film, which lasts seven minutes tells the simple story of a white basketball player who tries to impress a young black woman, but is quickly and comically upstaged by a more talented black player. Over the end credits, a rap song (by ‘Rockin’ Squat’) can be heard, singing ‘exploitation flows in the white man’s veins’. The same year Kassovitz also directed Peuples du monde, a music video for French black rapper ‘Tonton David’.

While working on Fierrot le pou Kassovitz had a crucial encounter with Christophe Rossignon, a young producer who would exert a significant influence on him. Rossignon helped Kassovitz finish Fierrot le pou and make another short, Cauchemar blanc, adapted from a famous strip cartoon by cult author ‘Moebius’ (Jean Giraud) about racism in the suburbs. The ten-minute black and white film shows four incompetent racist white men going on the rampage in a suburb one night, bent on attacking a North African man. Initially their attacks comically backfire: they crash their car into a telephone booth (which ends up on top of the car), one of them is knocked out, another pretends to be a policeman only to be arrested by a real (black) policeman. The silence and dignity of the North African contrast with the ludicrous rants of the whites – until we discover that this was all a dream, the ‘nightmare’ of the title. As the four men ‘wake up’, in the film’s chilling coda off-screen, they beat and probably kill the North African, who is left lying on the ground.

Mathieu Kassovitz, the director of La Haine, playing the male romantic lead in Le Fabuleux destin d’Amélie Poulain

At that point Kassovitz wanted to move on to making feature films, but Rossignon encouraged him to make a third short, Assassins, a story about violence that would act as a kind of pilot for his 1997 feature of the very similar name, Assassin(s). The 1992 Assassins, at 11 minutes, is longer and more accomplished than the first two shorts and it is in colour. It shows two brothers who murder an old man in a suburban house. Apart from the helpless cries of the man, who is savagely beaten and tied to a radiator, the film focuses on the older brother teaching the younger one (played by Kassovitz) to overcome his panic in order to perform the killing – a concern with male ‘education’ into violence that will resurface in the 1997 feature. While Cauchemar blanc was awarded the Perspectives du Cinéma Award at the 1991 Cannes Film Festival, Assassins was more controversial, provoking the ire of Socialist Minister for Culture Jack Lang, who wrote to Kassovitz that the film was an ‘incitement to murder’.7 Lang’s judgement may be over the top, but Assassins’ sadistic focus on the old man’s terror and the two killers’ semi-comic behaviour does raise some uncomfortable issues – in particular, the kind of spectatorial engagement that is sought by the film in which fascination for violence is close to celebration, despite an evident desire to ‘analyse’. For our purpose here, it is striking that the three shorts together condense the themes that are central to La Haine: the admiration for black men and hip-hop culture (Fierrot le pou), racism in the suburbs (Cauchemar blanc) and violence (Assassins). All three share a quasi-obsessive focus on troubled masculinity, which also prefigures La Haine and Kassovitz’s subsequent films. Stylistically, apart from the use of black and white in two out of three, the shorts show Kassovitz’s predilection for fluid long takes, which will reappear in Métisse as well as La Haine.

Kassovitz finally succeeded in making his first feature, Métisse, in 1993. In contrast to the male outlook of his shorts and, indeed, of La Haine, Métisse tells the story of Lola, a half-caste Catholic woman from the French West Indies (played by Julie Mauduech) who reveals to her two lovers, white Jewish Félix (Kassovitz) and black Muslim Jamal (Hubert Koundé), who until then are ignorant of each other’s existence, that she is pregnant and that either of them could be the father. In interviews Kassovitz has cited as a source for Métisse his own interrogation about what he would feel if his girlfriend went out with a black man, an autobiographical angle reinforced by the fact that Mauduech was his partner at the time.8 Beyond the autobiographical, as the title – which means half-caste – makes clear, the theme of race is central to Métisse, and the film again taps into French hip-hop culture with a theme rap song by ‘Assassin’ entitled ‘La Peur du métissage’ (fear of racial hybridity). The story is, however, treated in a lightly comic manner. The initially hostile rival male lovers end up best friends while looking after the heavily pregnant Lola. Although Félix is revealed by a test to be the biological father, both young men are united around the birth, which seems to solve all problems, in the tradition of French comedy (see Coline Serreau’s 1985 Trois hommes et un couffin and Josiane Balasko’s 1995 Gazon maudit, among others). The fact that Jamal is the son of a rich diplomat and a law student while Félix is a fast-food delivery man is refreshingly counter-stereotypical but, equally, serves to defuse serious issues around racism, given this atypical race/social hierarchy. Kassovitz comically indulges in blatant cinephilia, further emphasising the light aspects of the film: the plot echoes Spike Lee’s She’s Gotta Have It (1986), and the character he plays is an inept version of Lee’s Mookie in his own Do The Right Thing (1989) – Kassovitz’s outfit makes him look geeky (as in Fierrot le pou), and he endlessly falls off his bike and generally gets into trouble. Kassovitz’s emulation of Spike Lee, but also his adolescent fixation on black hip-hop culture, are recognised by the film (at one point Jamal accuses Félix of ‘playing at being the black man with [his] shitty rap music’), though not without self-indulgence.

With hindsight, what is also striking about Métisse is the degree of continuities with La Haine, notably in its cast. Hubert Koundé as Jamal anticipates Hubert (same actor, same wise persona) while Félix looks forward to Vinz and his Jewish family. Cassel, in a small role, plays Félix’s brother, thus emphasising the overlap between Cassel and Kassovitz, whose real-life fathers additionally both appear in cameo...