![]()

1

OVERTURE – ACROSS THE BRIDGE

L ondon, a warm summer evening during the mid-1890s. The sun is setting behind the Houses of Parliament and the prostitutes are on their way to work. Groups of them saunter across Waterloo Bridge, their dyed hair and gaudy costumes softened by the rosy light. They are heading towards the Strand, Leicester Square and Piccadilly Circus where the pubs, restaurants and music halls provide a ready source of custom. Come the early hours of the morning, they will make the weary return journey to their homes in Lambeth and Southwark. That is the direction that we now take.

On arriving at the other side of the bridge we soon encounter a major crossroads: Stamford Street to the left, Waterloo Road running straight ahead, with York Road and the South Western Railway terminus to the right. Close to the station a few men stand drinking under the hanging gas lamps of the York Hotel. Earlier in the day the pub and the adjacent pavements of ‘Poverty Corner’ would have been packed with performers hoping to obtain last-minute music-hall bookings from the many variety agents who occupy the area. A glance across the junction reveals Wolf Goldstein’s old offices from where ‘Dashing’ Eva Lester was ejected after trading blows with her theatrical representative. The district is seedy and down-at-heel with many lodging houses catering for the ‘work girls’ of ‘Whoreterloo’. Moving onward towards the New Cut we pass St John’s Church, an imposing neo-classical edifice that stands out from its dingy surroundings. Here the great Dan Leno’s parents were married and more recently the patriotic vocalist Leo Dryden brought his abducted son to be baptized.

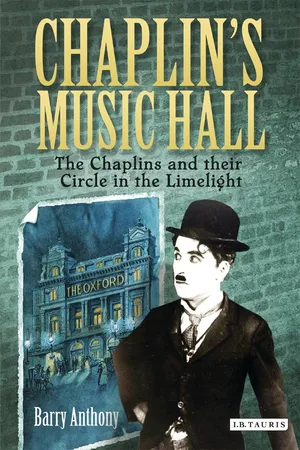

ILLUSTRATION 1. ‘Across the Bridge’. Charles Godfrey’s hit song of 1888 concerns transience, love and despair.

Approaching another large crossroads, we see the substantial frontage of the Royal Victoria Theatre, familiarly known as the ‘Old Vic’. We do not carry onward towards Bethlehem Lunatic Asylum and the Walworth Road, but turn into Lower Marsh, a narrow thoroughfare which plays host to a clamouring street market. Crowds of impecunious shoppers gather round stalls selling flowers, crockery, second-hand books, even spectacles. Street hawkers offer cheap toasting forks, boot-laces, braces and badly printed song sheets pirated from the more expensive publications of Francis, Day and Hunter and Charles Sheard. Running across the far end of the market we see, and hear, Westminster Bridge Road, its heavy traffic grinding northward to the Thames and south to the distant, green fields of Kent. On the far side of the road stands a tall building, designed in the Italianesque style. Bright lighting illuminates the colourful posters and florid decorations of the Canterbury Theatre of Varieties, a music hall that has dominated this corner of Lambeth for the past 40 years. The theatre has long since outgrown its humble tavern ancestor, but everyone remembers that back in the early 1850s Charles Morton took the old Canterbury Arms and converted it into the first modern music hall. Everyone remembers this because the venerable Charlie is still around to remind them. Although advanced in years, he continues his distinguished managerial career at the newly built Palace Theatre in Cambridge Circus.

A smaller hall, Gatti’s, stands on this side of the road, built close to the brick viaduct of the station. At its entrance a lady of easy virtue is accepting a gift from a smartly dressed gentleman – a risky business considering the recent exploits of the Stamford Street poisoner Dr Neil Cream.1 Against the dank wall beneath the railway bridge a blind beggar has taken up a position that he is set to occupy for many years to come. We leave him fingering a grubby Braille bible and continue along the Westminster Bridge Road. A couple of trams have stopped, giving their horses the opportunity to catch a moment’s rest. Other vehicles slow down, coming to an impatient halt. There are hansom cabs, tradesmen’s vans, pony traps, and buses whose occupants lean over the top deck to see what has caused the delay. A crossing sweeper takes the opportunity to clear a path from one side of the road to the other, pushing the grainy balls of horse-dung into a heap that intermingles with multi-coloured bus tickets.

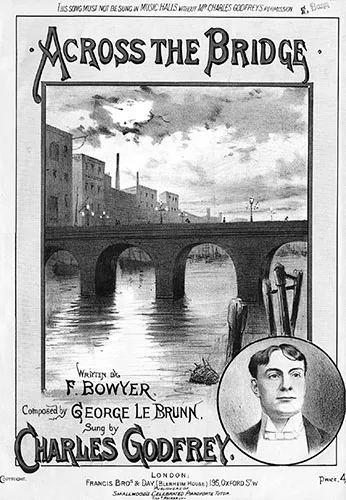

A sign on the left announces Lambeth Baths, not only a centre for physical recreation, but a venue for mass social and political meetings. On the right the oyster rooms are doing a brisk trade. Directly in front of us the spire of Christ Church presents a sharp outline against the darkening sky. Although built in the Gothic style, the church is less than 20 years old. Its opening in 1876 occurred 100 years after the start of the American Revolution and much of the money for its construction was raised by donations from the charitably inclined citizens of the United States. Westminster Bridge Road extends to the left of the church, but we take the right fork. The road before us is broad and straight, with lines of softly glowing street lamps stretching as far as the eye can see. Kennington Road is long both in distance and in history. It was created in 1751 across open land to link Westminster Bridge with Kennington Common and thence the south coast. Now, hemmed in by narrow streets of jerry-built dwellings, it still appears spacious and airy. Its eighteenth-century terraces are well proportioned, with large windows and fanlights over panelled front doors. But these elegant houses are as crowded as the back streets, partitioned into apartments that make a mockery of their original symmetry. Taken as a whole, the boroughs that constitute south-east London are grossly overpopulated, accommodating some two million people within an area whose dimensions scarcely measure 6 by 12 miles.

ILLUSTRATION 2. Westminster Bridge Road, 1896, looking toward Christ Church.

Once past Christ Church the first major building on our left is the police station. Of lesser note is the York, a common beerhouse, and then, at the corner of the junction with Lambeth Road, the Three Stags. It’s at this pub that the Terriers, a philanthropic society of music-hall performers, hold their weekly ‘Grand Ceremonial Meetings’. We will pass several public houses on our progress along the road. On the west side are the Tankard, the Ship and the Roebuck and on the east side the Crystal Fountain, the Prince George and the Cock. Come Sunday morning these taverns will provide the backdrop for one of London’s best free shows as over-dressed, over-exuberant variety performers take the air and a ‘drop of something’ along the way. Tonight the pubs are busy but not crowded, music from impromptu concerts drifting into the street.

Although some shops remain open until a very late hour, many tradesmen are closing their premises, hauling heavy wooden shutters across the windows. In the private houses most of the front room curtains have been drawn, with occasional chinks of light betraying the presence of inquisitive or guilty occupants. The warmth has lured a few people outside. Some chat across cast-iron railings, others sit on the front door steps. Outside number 267 Mrs Allgood talks to her son. Perhaps they are recalling the time when the extempore vocalist Arthur West came to their lodging-house at two in the morning, punching young Ernest on the nose when he answered the door. He was looking for Jenny, his runaway wife. Or was she his wife? It’s not always easy to tell in the Kennington Road. As with the prostitutes, large numbers of music-hall artists are attracted by the proximity of the area to central London. Many guardians of public morality consider that the variety profession is synonymous with prostitution, an opinion perhaps satirized by performers who refer to themselves as ‘pros’ or ‘prossers’.

The major stars hold court in commodious villas in nearby Clapham and Brixton, but many lesser lights live in and around Kennington Road. At the moment the Craggs, ‘Gentlemen Acrobats’, have a private gymnasium at number 68; the sketch artist Fred Karno is at 86; Lauck and Dunbar, ‘America’s Greatest Double Somersault Flying Trapeze Artists’, reside at 133; while the Sisters Flexmore, singers of ‘The Art of Making Love’, have a temporary home at 265. A few months ago number 88 witnessed a tragedy when the American quick-change artist Robert Lorraine blew out his brains after being unable to repay loans to his landlady and the manager of the Tankard. Number 289 also has a gloomy history. It was there that the famous cannon-ball catcher Captain Athya died, not like Lorraine of gunshot wounds, but lingering consumption. An apartment in the same house served as the base for the swindler George Edward Bishop who was sentenced to a year’s hard labour for running a bogus theatrical agency.

Kennington Cross is not a religious monument, but the area linking Upper and Lower Kennington Lane. To the left the Lane leads to Renfrew Road where the local Police Court and Lambeth Workhouse stand in baleful proximity. Having no immediate business with either the Magistrate or the Workhouse Master we press on, soon passing another much-resented manifestation of municipal authority, the Town Hall. Across the way a few sooty trees surround a small open space known as Kennington Green. Finally, at the very end of Kennington Road, we are confronted with one of its most imposing buildings. It is a public edifice, but not of overtly civic function. Surmounted with giant antlers, the Horns Tavern is an extensive, confident building with a wealth of terracotta ornamentation. Its adjoining assembly rooms have hosted all kinds of entertainments, including benefit performances for variety performers down on their luck. Outside the Horns a small, curly-haired boy is singing. He deserves a few pennies, for his impersonation of the great ‘coster’ comedian Gus Elen is surprisingly accurate:

‘E ’as the cheek and impudence to call ’is muvver, ’is ma,

Since Jack Jones come into a little bit o’ coin,

Why ’e don’t know where ’e are!

* * *

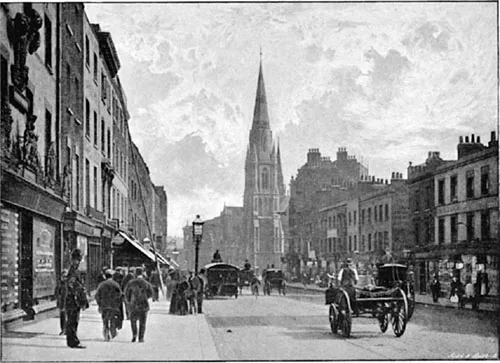

ILLUSTRATION 3. Kennington Road in the early 1900s. Posters advertise the Canterbury Music Hall, the South London Palace and the Empress Theatre of Varieties, Brixton.

This evocation of late Victorian Waterloo and Kennington is partly based on Charlie Chaplin’s recollections of the area as it was when he lived there with his performer parents. He was to recreate aspects of this world in many of his films, most significantly in Limelight, his tribute to the music hall. The autobiographical references found in the film were drawn from a preparatory treatment, a 100,000-word unpublished novel that Charlie worked on over a period of years. In the rambling text of Footlights he filled in the backgrounds of the film’s two central characters; Calvero, a washed-up comedian played by Charlie, and Terry, a washed-out dancer played by Claire Bloom. In much of his written work, particularly My Autobiography, Charlie conflated characters with memories of south-east London. The emotional content of particular scenes was frequently heightened by their atmospheric settings. The closing-in of his mother’s madness took place at the top of a ‘rickety’ staircase in the claustrophobic garret of 3 Pownall Terrace, Kennington Road. ‘The room was stifling,’ he wrote, ‘a little over twelve feet square, and seemed smaller and the slanting ceiling seemed lower.’2 Charles Chaplin Senior’s self-destructive nature was suggested by the furnishings of the apartment at the unlucky 289 Kennington Road: ‘the stuffed pike in a glass case that had swallowed another pike as large as itself – the head sticking out of its mouth – looked gruesomely sad.’3 Charlie discovered the power of music outside the White Hart, Kennington Cross, while his first love blossomed a little further along the road at Kennington Gate. Kennington Park was synonymous with loneliness, its benches remembered for their ‘treacherous bleakness’.4

Some of Charlie’s most vivid childhood memories were of his mother, deserted by Chaplin Senior, trying to maintain an air of respectability as she and her two sons moved from one set of sordid lodgings to another. She did her best to patch their tatty clothes and to impose standards of speech and behaviour. Despite Hannah Chaplin’s best endeavours, it was Charlie’s cockney accent that won him his first major role on the stage. As Billy the impudent newspaper boy in Jim, A Romance of Cockayne he found himself commended in the theatrical press and, of greater importance, in receipt of a regular income. It was a salutary lesson that one’s imagined weaknesses might, in fact, be abiding strengths. If only the drunks and derelicts who shuffled the streets of Kennington could have turned their afflictions to such advantage. They, of course, could not, but Charlie, under Hannah’s perceptive tutelage, was able to study their idiosyncrasies and, in the course of time, to replicate them to devastatingly funny effect on stage and in films.

Charlie was an observant bystander on the road to ruin. As a child he soaked in the dysfunctional, disordered world of his parents and their circle of acquaintances. In them he was to recognize the absurd pretensions of shabby-gentility; the ludicrous discrepancies that existed between stage fiction and everyday reality; and, above all, the extremes of behaviour caused by popularity and rejection. ‘Comedy,’ he reportedly observed, ‘is life viewed from a distance; tragedy, life in a close-up.’5 The characters in the tragicomedy of Charlie’s youth were a group of music-hall folk who inhabited the same small area of London and whose lives were sometimes intimately and disastrously linked. Their personal ups and downs were paralleled by a profession in a state of crisis. Solo ‘turns’ like Charlie’s parents struggled to make an impact in the oversized variety theatres which began to spring up during the 1890s. Major tensions arose as performers schooled in ‘free and easy’, tavern-based entertainment attempted to meet the increasing demands of businessmen running the music-hall industry. Eventually, having lost touch with its audience, music hall surrendered its popularity to cinema. Some performers migrated from the old entertainment to the new. Others remained, watching their careers fade away with the last music halls.

Charlie monitored the decline and fall with mixed feelings. Music hall, which both made and destroyed his parents, had provided him with an escape route from the slums of south-east London. But in becoming the silent cinema’s premier comedian he had helped destroy the older institution. As years passed and his own form of cinema became outmoded and undervalued, he grew nostalgic for the entertainment and entertainers of his childhood. He was to spend much time reflecting on the turbulent lives and careers of his parents and their friends, finally reconciling their triumphs and disasters in his own gritty philosophy of success, failure and, above all, survival.

![]()

2

‘DASHING’ EVA LESTER – THE CALIFORNIAN GEM

She stood like a stag at bay, hounded by a group of boys who mocked her filthy clothes and closely cropped hair. Once she had charmed audiences with her fashionable dresses, good looks and natural vivacity – now the lads pushed each other forward, as if merely touching her would cause immediate contamination. ‘Dashing’ Eva Lester’s fall, like her rise to music-hall fame, had been rapid. In common with many variety performers she had lived beyond her means, existing on a day-by-day basis with little idea how she might provide for h...