![]()

1

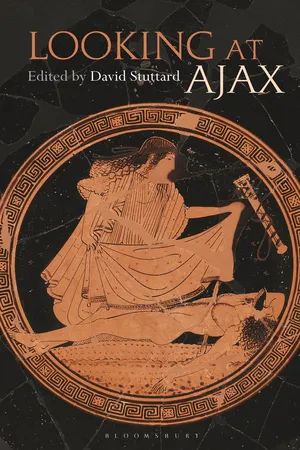

Some Visual Influences on Sophocles’ Ajax?

David Stuttard1

Time stretches to eternity. It brings all things into the light and buries them again in darkness. All is inevitable. Nothing can resist – not even the most binding oath or the most steadfast will.

Sophocles, Ajax, 646–9

For those familiar with the character of Ajax only from his appearances in the Iliad and Odyssey, his philosophical utterances in Sophocles’ play can come as a surprise.2 In epic, Ajax is the quintessential tight-lipped warrior, second only to Achilles in might and main. In fact, at Troy these two site their tents on either wing of the Greek encampment, those dangerously liminal positions that were potentially so vulnerable to attack (Iliad, 8.226; 11.7–9; cf. Sophocles Ajax, 4), and, when Achilles withdraws from battle to nurse his slighted honour, it is no coincidence that his cousin Ajax, like him a man of action, is chosen as one of three ambassadors who try (albeit unsuccessfully) to change his mind (Iliad, 9.182–668), complementing perfectly the silver-tongued Odysseus and wily old Phoenix, Achilles’ erstwhile tutor.

In Achilles’ absence, Ajax readily assumes the role of Greece’s champion. Several times he pits his strength against Hector, the most courageous of the Trojans, not least when Hector leads a Trojan attack on the Greek ships (Iliad, 15.674–745; cf. Sophocles, Ajax, 1276–9) or when the two fight as champions in single combat to decide the outcome of the war (Iliad, 7.66–305; cf. Sophocles Ajax,1286–7).3 In a hard-fought struggle, Ajax wounds Hector with his spear and knocks him over with a heavy stone, but the god Apollo protects the Trojan, and the battle lasts till nightfall. As darkness draws in, Hector suggests that they not only suspend hostilities but exchange gifts (Iliad, 7.299–305):

Come, let us give each other glorious gifts, so that any man, be he Greek or Trojan, will say: ‘Each fought the other with heart-gnawing venom, but before they parted they were joined in friendship.’ So saying, he gave Ajax his silver-studded sword, together with its scabbard and a well-cut sword belt, while Ajax gave Hector his shining purple battle-belt.

Although the Iliad makes little of it, this exchange of gifts becomes a defining moment in the fate of both warriors: in later Greek tradition, Ajax commits suicide with Hector’s sword, while, using the battle-belt the Trojan received from Ajax, Achilles ties Hector’s corpse to his chariot before dragging it around his friend Patroclus’ tomb.

While the action of the Iliad ends before the contest for Achilles’ armour (in which Odysseus defeats Ajax) and Ajax’s resultant suicide, in the Odyssey when Odysseus encounters the soul of the still-resentful Ajax in the underworld (11.543–67) both episodes are alluded to in such a way as to suggest that readers (or listeners) were expected to be familiar with them.4 Indeed, for those who know the story, even the Iliad contains hints of things to come. In Book 23, Ajax takes part in two events in the funeral games that Achilles holds in Patroclus’ honour: a fight against Diomedes with spears in which neither party wins, and a wrestling contest with Odysseus, which, although Odysseus appears to be gaining the upper hand, Achilles stops early, declaring it a draw.

It is not the only time in these games that Odysseus gets the better of an Ajax. Odysseus wins the footrace with the help of his patron goddess, Athene, who trips his rival, another Ajax, this time the son of Oïleus, sending him face-first into a pile of ox-dung. Realizing the cause of his misfortune, this ‘Lesser’ Ajax exclaims:

‘Damn it! The goddess hobbled my feet – the goddess who always stands by Odysseus like a mother, and helps him.’

Iliad, 23, 782–3

Again, this idea of Odysseus gloating over a rival, laid low by his protectress, Athene, will resonate in later episodes of the Trojan War, and inform not just the action of Sophocles’ Ajax but (as we shall see) the work of vase painters.

As discussed in the Introduction to this book, the Iliad and Odyssey deal with only two parts of the Trojan War and its aftermath, so in the centuries after their conception a number of other epic poems (of varying quality) were written, drawing on earlier myth, whose subject matter filled in the blanks to complete the story of the war from its first causes to the death of Odysseus. While all survive only in fragments, we know that in the Aethiopis (which begins where the Iliad ends), when Achilles is shot in the ankle by the Trojan Paris aided by Apollo, Ajax carries his body to safety, while Odysseus beats off assailants.5 The Little Iliad describes what happened next: when Ajax and Odysseus both claim Achilles’ armour (forged by the god Hephaestus), the decision is put to a vote; again Athene helps Odysseus to win; Ajax goes mad and, thinking that he is attacking the Greek commanders, slaughters their cattle instead; when his senses return, he is so humiliated that he commits suicide, but, instead of the usual heroic cremation rites, he is buried without honour.6

In epic, then, Ajax is an action hero, a mighty warrior, a man of deeds, not words, who fearlessly strikes down his foe, and, when humiliated by both gods and men, turns his blade swiftly and efficiently upon himself. But by the time we meet him in Sophocles’ play, he has become transformed. He is still the fearsome warrior, but now he is more: an apparently deep thinker, whose speeches increasingly blend notions of heroic honour with contemplations of the cosmos and man’s place in nature.

If we confine ourselves to extant literary tradition, we might be excused for thinking that this transformation was the work of Sophocles alone. Yet literature was not the only medium by which myth might be explored in Ancient Greece. Vase painters, too, drew inspiration from the Trojan War, and some of their treatments suggest that already by the 530s BC they were using episodes from the life and death of Ajax to explore issues that bordered on the metaphysical.

Sixth-century BC artists embraced Ajax.7 For centuries formulaic scenes had been stamped on Samian amphorae showing a helmeted warrior carrying a fallen comrade – but now, through the use of captions, painters began to identify many of these depictions as representing Ajax rescuing Achilles’ corpse from the battlefield. No captions were needed, however, for representations of another popular episode: Ajax’s suicide. Painters delighted in showing him impaled on his sword, their composition mirrored in a sculpture from as far away as Southern Italy (a metopé from the so-called Temple of Hera in Paestum), while a Corinthian black-figure cup from around 580 BC depicts Greeks including Odysseus apparently debating over Ajax’s impaled corpse.

But it was the mid-sixth-century BC Athenian, Exekias, whose work took the visual representation of the myth of Ajax to new heights, using a purely visual vocabulary to explore it with almost literary eloquence and extraordinary profundity. Let us look first at one of his most remarkable paintings (Fig. 1, now held in the Vatican Museum).

Sitting perfectly within the curves of the amphora, it is quite simply a masterpiece. For sheer composition it is second to none in its use of available space, as the diagonals of the spears and of the heroes’ arms, not to mention the direction of their gaze, all focus our attention on the board game, while at the same time our eye is directed to the arc of the handles by the spear tips and the seemingly-so-casually placed shields. It shows a scene for which there is no parallel in earlier literature, so may well be Exekias’ own creation: Ajax and Achilles competing for victory and kudos not in the kind of athletic games that feature in the Iliad, but in a board game. In it, the two cousins, apparently during a lull in the fighting, are bent over the board, their interest completely taken up in it. Both wear elaborately patterned cloaks. Both clutch spears. But only Achilles is helmeted, and we know that he will win. For, beside him, Exekias has written the word, ‘Tesara’ (‘Four’), while beside Ajax appears ‘Tria’ (‘Three’).

Figure 1 Exekias’ Board Game.

Further consideration of the composition reveals more. As we have already seen, Ajax and Achilles, the two bravest fighters in the Greek army, positioned their tents at the two flanks of the encampment, trusting, Homer tells us, in their courage and the strength of their hands. Here, too, in our painting, the two heroes flank a contest – this time a board game, but one that is arguably a metaphor for an altogether more serious contest, a contest of which every Greek hero was desperately aware, the contest ‘always to be best and to surpass all others’ (Iliad, 6.208; 11.784). ‘Always to be best’ means, of course, ‘always to win’, and here in the board game Ajax and Achilles use ‘the strength of their hands’ to shift the pieces until one of them should do j...