![]()

PART I

When Bergholz Changed

![]()

1

WITNESS FOR THE PROSECUTION

I stared at the courtroom door in front of me and took a deep breath, trying to figure out how things had gotten to this point. I was only an Amish kid working construction and selling horses on the side. I didn’t know anything about trials or courtrooms or hate crimes. I didn’t know anything about perjury or federal statutes or juries. I definitely didn’t know anything about being a witness for the prosecution.

But on that day, that’s exactly what I was.

I walked into the courtroom. I wondered when I’d be asked about the camera. I wondered how much the lawyers had heard about Sam and his relationships with the women in our community. I heard a few whispers as I walked down the aisle, and then everyone grew silent as I took the stand.

I had been called there to testify against my grandfather, Samuel Mullet, as well as the other men and women in our Amish community who had been involved in the things that had happened during the previous year.

My knees felt like jelly. The bailiff swore me in. I was glad to sit down, even if it was in the witness stand. The judge was to my left, and he spoke first. He was matter-of-fact and firm.

“All right. I’m advising you that your testimony is being compelled, pursuant to federal statute Title 18. Sections 600(2) and 600(3), and that as a result, no testimony that you give in response to questions can be used against you in any future criminal proceeding.”

He paused and shuffled through some papers in front of him.

“However, should you testify falsely in any manner, the statements could be used and you could be prosecuted for perjury. Do you understand this?”

I tried to keep my voice even, but it had a life of its own.

“Yes,” I said.

“All right,” the judge stated. “Do you have any questions about this, sir?”

“No,” I said.

“Okay. Thank you,” the judge said.

Both the prosecution and the defense wanted to use me for their own purposes, and I had met with them in the months and weeks leading up to the trial. “Don’t say more than you have to,” Sam’s attorney had stressed to me during pretrial meetings. “If you can answer with only a yes or no, do it. Try to get the attorney to phrase the question so you can answer simply yes or no. Otherwise, just say ‘I don’t know.’”

The prosecuting attorney stood up and walked around to the front of her table. My grandmother (Sam’s wife) and all the spouses of the defendants sat in chairs on the left side of the courtroom. Amish people from other communities sat on the right. There were reporters and a lot of people I didn’t know. The room was full and quiet. I wasn’t sure where to look. I cleared my throat and took a deep breath.

“Good morning,” the attorney said to me. “Please state your name and spell your last name for the record.”

“Johnny Mast,” I said. “M-A-S-T.”

“Mr. Mast, where do you live?”

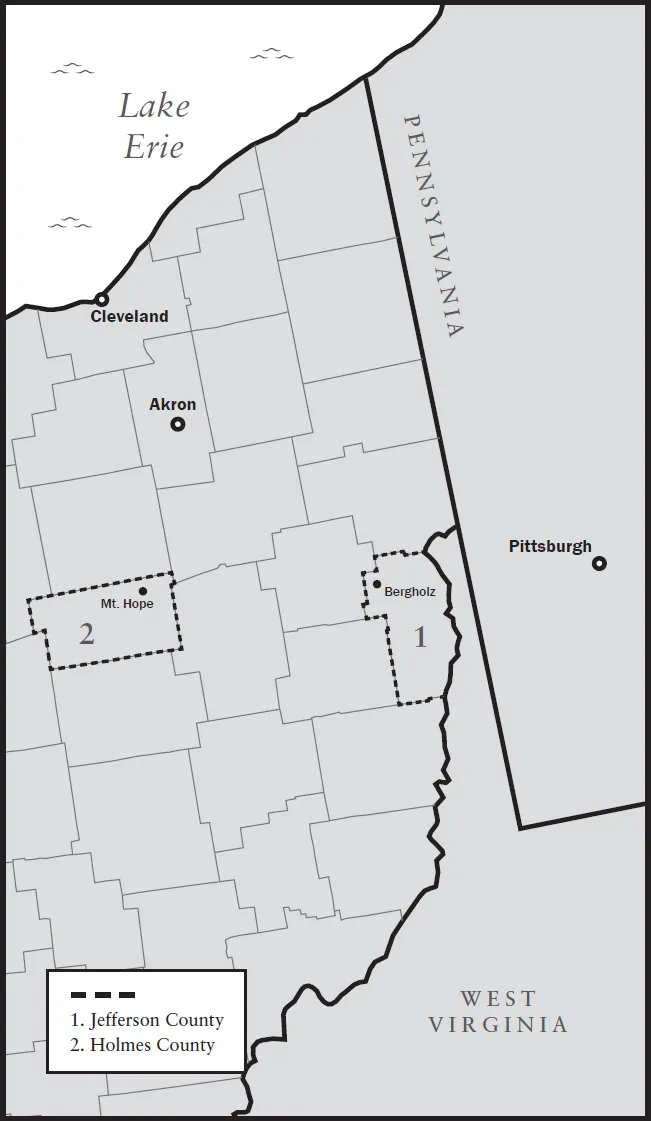

“Bergholz, Ohio.”

When I said the name of our town out loud, I thought about all the things that had been written about us in the newspapers. The Bergholz Beard Cutters.

All sixteen defendants, including my grandfather, sat at different tables in front of me, a little to the left. I’m sure they were nervous about what I would say and how my words would affect them. Some of them faced years and years in prison. The men’s hair was flat against their heads from the hats they wore that morning on the way to the courthouse. They stared blankly at the table or the wall at first, but at the sound of my voice they looked up at me.

“And where specifically in Bergholz, Ohio, do you live?”

“I’m at my parents’ place.”

“Are you related to defendant Sam Mullet, Senior?”

“Yes.”

“And how is that?”

I took a deep breath.

“He’s my grandfather.”

I glanced over at Sam and he returned my gaze with a mischievous sparkle in his eyes. He grinned and nodded. He had been nothing but supportive to me in the days leading up to my testimony, even though I was supposed to testify against him. He encouraged me to tell the truth and to remember the advice his lawyer gave me. I couldn’t help but give a small smile back before looking away. I knew I probably shouldn’t look at him. I couldn’t believe I had to testify against him. He had done a lot of strange things, a lot of things I didn’t understand. But he was still my grandfather.

“And so Samuel Mullet’s sons are your uncles?”

“Yes.”

“And defendant Linda Shrock is your aunt?”

“Yes.”

I settled into the game of questions and answers. Questions and answers, and every so often objections by the other attorneys. Yes and no and I don’t know and more objections.

“How old are you, Mr. Mast?”

“Twenty-two.”

“Have you been baptized into the Amish church in Bergholz?”

“Yes.”

“Was there a time when members of the Bergholz community cut each other’s hair and beards?”

I paused. I saw images in my mind that made me wince. Images I’d rather forget: Holding my own father’s hair in my hands and cutting off pieces with a pair of scissors. Watching six or seven men wander down toward Sam’s barn, chunks of their hair shaved off, their beards cut straight across with sharp scissors. I remember seeing those disheveled men, skinny from not having eaten, their weird hair and their hats that no longer fit quite right, and thinking they looked like demons.

“Yes.”

“When did that first start happening?”

“Probably about three years ago.”

“And what was your understanding of what the reason for it was?”

“Because they weren’t living their life the way they knew they should, and they wanted to turn their life around.”

It made me nervous when I gave long answers. I was scared of the words coming out of my mouth, scared that they would somehow implicate Sam or the others.

“So it was a symbol of a new start?”

“Yes.”

“Did you ever have your hair or beard cut during this time?”

“No.”

“Were you present when others had their hair or beards cut?”

“Yes.”

Again I pictured my own father, and I heard Sam’s voice. C’mon, Johnny, cut off some of your dad’s hair. You’re mad at him too, aren’t you?

The attorney kept firing questions at me. I concentrated, tried hard to keep my answers short.

“Was Sam Mullet, Senior, aware of the practice of beard cutting within the community?”

“Yes.”

“And did some of the beard cuttings actually take place in his presence?”

“Yes.”

“What was your understanding of what Sam Mullet, Senior, thought of these beard cuttings in terms of their ability to help people turn their lives around?”

Sam’s defense lawyer called out, and it startled me.

“Objection!”

“Sustained,” said the judge, nodding.

The prosecution paused, then asked the question in a different way.

“Did you ever discuss these beard cuttings with Sam Mullet, Senior?”

“Could you ask that question again?” I asked.

“Yes. Did you ever discuss the use of beard and hair cuttings within the community with Sam Mullet, Senior?”

“Yes.”

“And what did he say about the use of beard and hair cuttings when you discussed it with him?”

“He didn’t know if it would be the right thing to do or not. He wasn’t sure.”

The attorney turned around and looked at papers on her desk, then turned toward me again.

“Did there come a time you heard members of the Bergholz community talking about cutting the head and beard hair of Amish people who lived outside of the community?”

I paused. This was exactly why we were all there. I remembered the Millers, the Hershbergers, the Shrocks. I remembered being handed a trash bag full of hair and being told to burn it out back. I remembered the sound of shouts. I remembered the sound of a man’s roar, a man who was trying to defend himself.

“Yes,” I said.

![]()

2

THE MOVE TO BERGHOLZ

I fell in love with horses long before we moved to Bergholz, back when I was only five or six years old and my dad took me to the Mount Hope horse auction. He was in the market for a team of workhorses, and I was excited when he asked me to go along. We got there and I looked around in awe. There were horses everywhere, some moving and restless, others standing still as statues. They were different colors, different temperaments, and I wanted to pet them all. There, at my first horse auction, I was filled with this desire to own horses, and lots of them.

Dad bought two workhorses on that particular morning: nice ones. Our driver hauled them home for us. The Amish travel mostly by horse and buggy, but if they need to go somewhere too far for that, they hire a non-Amish person to drive them around. It’s a common thing, and some drivers make a full-time living just driving Amish folks from here to there.

I remember the first time we hooked the horses to the big old box wagon before heading out to the woods to get firewood. I was standing in the box, and Dad let me drive our new horses. I felt like a million dollars, even though the horses were tame and probably could have done it on their own. When I felt the horses’ energy come through the reins, I knew I was a horse man.

I know everyone says tractors are better, and of course I agree that they’re faster. But I always found something peaceful about being up there behind the horses, the sound of the wagon creaking through the field, the horses’ tails swishing away the flies. It’s quiet when you’re out in a field driving horses. It feels like there’s nothing else in the world.

Not too long after my dad bought those workhorses, I got my first pony. We bought it from my uncle. When my dad brought it out of the trailer, my brother Floyd held it by the lead rope. The pony came out and stood there quietly, eating grass. But it must have stepped over the lead rope, because when my brother pulled the rope taut, it tightened up under the pony and startled it. That crazy pony—it ran off and got away from us. We couldn’t catch it. We ended up chasing it all over the neighborhood, through fields and people’s yards. It was taller than me and ornery as anything. I was scared half to death of that sucker, and even though I was chasing it, I secretly hoped my brother would be the one to catch it.

I’ve always felt a connection between me and my dad and my horses, probably ever since he took me to that horse auction when I was little. I miss having horses. I miss Bergholz the way it was when we first arrived.

It would be nice to see my dad again, to be able to have a regular conversation. But what happened in Bergholz ruined all of that.

I was eleven years old when we moved to Bergholz, Ohio. We had been living in a community about 120 miles west of there, but I wasn’t sad to be leaving that place. I don’t think any of us in the family were. It never felt as if that first community accepted our family. For some reason I felt that we were looked down on, pushed out to the side, and I didn’t have any close friends there. Sometimes I’d play with other boys, but as soon as someone else showed up, I was alone again.

When we moved to Bergholz, everything changed for me.

The town of Bergholz still looks almost the same as it did the first time we approached it in a moving truck, driving on those back country roads. I liked the mountains, the way the land rose and fell with lots of hills and valleys. There are more houses now than there were when we moved there, mostly because of all the gas wells going in. But even now there are roads in Bergholz that will take you to places way back in, miles from any other houses.

My grandfather, Sam Mullet, had started the Bergholz Amish community six or seven years before we moved there. He and my grandmother bought a farm about three miles outside of town, and a few families—mostly his children, my aunts and uncles, and their families—followed them. There’s a little old dirt road that goes back to his place, lined for a little ways with a wooden fence that my brother Edward and I built.

The community started their own church, as Amish communities do when they start up in a new area, and Sam became our bishop. It made sense at the time. Who else would lead the new community? Most of the men there were Sam’s sons or sons-in-law. Sam had bought the first piece of land. The whole community had been Sam’s idea.

Bergholz was a whole new world for me. I was suddenly surrounded by tons of cousins who became my best friends. I attended our Amish school with thirty o...