![]()

Chapter 1

On Cloverdale Farm: 1892–1912

“Our fathers gave both Harold Bender and me a home and church life advantage.”

On a wintry night in about 1912, Daniel D. Miller drove his horse and carriage from his home on Cloverdale Farm near Middlebury, Indiana, to Goshen College some fifteen miles away. Daniel, or D. D., was bundled up against the snow, still falling after a midwestern blizzard the day before. A trim man at five feet six inches and 125 pounds, he was also intense, determined, and on a mission. D. D. was a widely traveled evangelist, bishop of numerous Amish Mennonite (AM) congregations, and an officer on various Mennonite Church boards. But tonight he was worried about his oldest son, Orie.

Orie was a Goshen College student, but not an ordinary one. He was also the principal and teacher of Goshen’s academy-level Commercial School of Business. He was a serious student and a sober teacher—too much so for some of his students. Neat and trim, at five feet ten he was four inches taller than his father. A country boy, sometimes sarcastic and inclined to criticism, he lacked the genteel manners of his later years.

Orie was surprised to see his snow-covered father appear on campus. D. D. had a book in hand, one that Orie had given him to read on Sunday. The Monday snowstorm had given D. D. all day to read the book. Father and son were close, each having high regard for the other. Typically, they shared a common mind, but not when it came to this book. Sixty Years with the Bible: A Record of Experience by William Newton Clarke had pushed Orie to think new thoughts about the Bible: its origin, composition, and interpretation.

The “warmly evangelical” Clarke (1841–1912) was the premier American liberal theologian of the time. Sixty Years describes Clarke’s journey that began with a literal interpretation of an infallible and inerrant Bible, which he learned from his father. By the end of his journey Clarke had come to see the Bible as “a divine gift and a perpetual inspiration, but not as an infallible standard.”1 Historical and higher criticism had led him to a richer understanding of Scripture, not as an object of study but as “an expression of principles” and thus “a means of study.”2

Orie hoped the book could enlighten his father. D. D., on the other hand, believed that the book was dangerous and would take his son too far afield from an Amish Mennonite reading of the Bible. Why was this book in the library of a Mennonite college? The school’s critics, D. D. among them, believed that such books were symptomatic of the school’s growing modernism, a charge that would later lead to its temporary closing. Father and son talked long into the night without resolving their differences.

As Orie watched his father leave the campus and disappear into the wintry night, he was suddenly moved by his father’s extraordinary effort and concern. Even so, “I still felt that he needed the help more than I did,” Orie remembered nearly fifty years later.3 Orie’s son John W. Miller believes this book was formative for Orie, “open[ing] him to the world of the Bible in a pragmatic sense,” rather than an ideological sense, which is how fundamentalists viewed the Bible.”4

Despite their occasional differences, Orie and his father maintained a close relationship until D. D.’s death in 1955. They both, each in his generation, had a profound effect on the church they loved.

TWO AMISH FAMILIES

Orie’s parents, Daniel D. (1864–1955) and Nettie (Jeanette) Hostetler (1870–1938) Miller, were fifth-and sixth-generation descendants, respectively, of Swiss Amish immigrants. Their ancestors were among the five hundred Amish who emigrated between 1707 and 1774 from Switzerland, France, and Germany. Both families settled in the Northkill Amish community of Berks County, Pennsylvania, the earliest Amish settlement in the New World.

In 1757, during the French and Indian War (1754–63), Anna Hochstetler and two children were killed by a band of Lenni Lenape Indians and French scouts, while Jacob and two boys were taken captive. The older son, John, Nettie’s ancestor, who lived on his own property, witnessed the attack from a distance. He and his wife, Catherine Hertzler, were among the families who left the Northkill settlement to relocate in Somerset County, Pennsylvania.

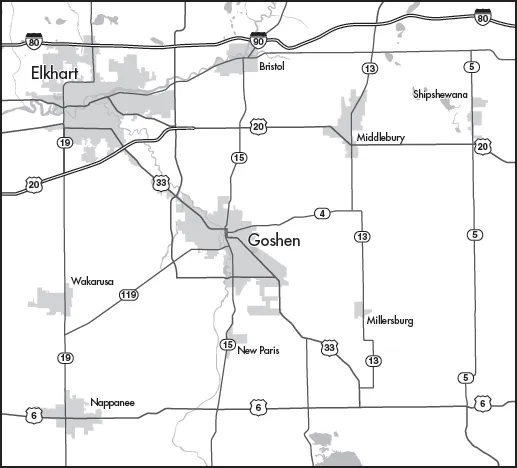

Future generations of Miller and Hochstetler families became part of a larger westward migration of Americans in the nineteenth century. The first Amish arrived in northern Indiana in 1841, only three years after Chief Shipshewana and his Potawatomie people had been deported. These Native Americans were forced to travel the infamous sixty-oneday “Potawatomie Trail of Death” to their exile in the Western Territory (Kansas). The aging Chief Shipshewana, however, returned to his homeland where he died in 1841 just as the Amish were arriving.5 Today over a million tourists annually visit the tiny town of Shipshewana, named for the Potawatomie chief, not to remember his people but to see the Amish who still live there.

In 1856, the Daniel P. (for Pennsylvania) and Anna (Hershberger) Miller family moved from the Conemaugh settlement of Somerset and Cambria Counties, Pennsylvania, to Newberry Township in LaGrange County, Indiana, where D. D. was born in 1864. Also in 1864, Moses J. and Elizabeth (Mast) Hostetler from Somerset County via Holmes County, Ohio, arrived in LaGrange County and settled on a farm near the small town of Emma. Here in 1870, Nettie (Jeanette) was born to Samuel J. and Catherine (Mehl) Hostetler.6

The Hostetlers (now using the anglicized form) were content to remain on their Emma farm. But wanderlust and the promise of economic opportunities persuaded the Millers to pack covered wagons and move roughly six hundred miles west to Hickory County, Missouri, in 1870 when D. D. was four. However, Missouri’s promise remained unfulfilled and prosperity a dream. The family lived in a small, rough cabin where D. D. and a brother made their sleeping “nest” under the kitchen table each night. In wintertime, snow often sifted into the cabin and onto the comforters under which they slept.

Area map: Forks, Cloverdale, Middlebury, Goshen, and Elkhart, Indiana. Reuben Graham.

Farming conditions were catastrophic. Hail, torrential rains, drought, hot winds, chinch bugs, and grasshoppers destroyed crops two years in a row. Mother Anna struggled to feed the family of eight, supplementing their daily diet of cornbread and water with mush and milk and, occasionally, wild game. According to family memory, had not Grandfather Joseph been an excellent shot, they might have starved. After four years of Missouri living, some of the Millers gave up and started back to LaGrange County, with fifty dollars supplied by Indiana friends. It took four weeks of walking, riding, herding cattle, and sleeping by the roadside to get back to Indiana.7 For eight-year-old D. D. Miller, the years of Missouri deprivation and the long journey home were unforgettable—experiences he later recalled for his children and grandchildren.8

Perhaps it is no surprise, given the hardscrabble experience in Missouri, that farming never occupied D. D.’s best efforts. Early in life, he determined to be a schoolteacher. Despite his parents’ reluctance and his grandmother’s persistent fear that education would destroy his faith, he pursued his goal. One of his teachers provided an alternative model. D. (Daniel) J. Johns was also an Amish Mennonite minister, proving that education and faith were not incompatible. After finishing country school, D. D. prepared for teaching by attending the LaGrange Normal School. At sixteen, he passed the requisite examinations and began teaching in country schools, continuing for twenty terms—four at Garden City, Missouri, and sixteen at a variety of Indiana schools. While teaching at the Emma school, beginning in 1888, D. D. lived in the home of one of his students, Nettie (Jeanette) Hostetler. A year later, on May 26, 1889, they married and made their home with the Hostetlers.

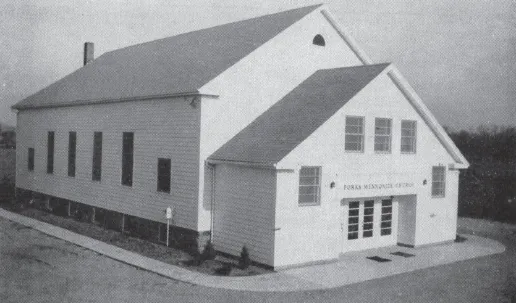

A CLARION CALL TO ACTIVISM

D. D. had been “soundly converted” at the Sycamore Grove congregation in Garden City, Missouri. After his return to Indiana, he was active in the Forks Amish Mennonite Church in Newberry Township, six miles from Middlebury. (Amish Mennonites had emerged as a progressive wing of the Amish after 1850.) In 1890, a year after his marriage, D. D. was ordained as deacon at the Forks church. Two more ordinations followed: as minister in 1891 and as bishop in 1906.

Forks Mennonite Church, 1949 meetinghouse. Ernest E. Miller, Daniel D. Miller: A Biographical Sketch.

With his ordinations came a passion for evangelism, which took D. D. to Amish Mennonite and Mennonite congregations across the country. His itinerant ministry took him away from home, sometimes for as long as six weeks at a time and for as much as six months a year—a life Nettie and the children learned to accept. Not so father-in-law Samuel J. Hostetler. He objected not only to D. D.’s frequent absences from home but also to his revivalist preaching, a departure from the Amish tradition of a communal discipleship-based faith. Hostetler offered the home farm as leverage to keep his son-in-law at home, but to no avail. D. D. had a mind of his own and a calling to follow.9

In addition to his congregational responsibilities as a bishop and his itinerant ministry as an evangelist, D. D. became an institution builder and manager. He was not a visionary, but his judicious business sense, strong administrative skills, and levelheaded counsel made him a valuable member of boards and committees that directed the church’s education, mission, and service ministries.10

In 1890, there were 41,541 Anabaptist heirs—Amish, Mennonites, Brethren in Christ, and Hutterites—in the United States. The largest group among them was the “old” Mennonite Church (MC), numbering 17,078. In the decade between 1916 and 1927, Amish Mennonite adherents who had left the Old Order Amish joined MC conferences, and by 1926 the MC population in the United States was 34,039.11

In the spirit of the times, Mennonites and Amish Mennonites held a large gathering in northern Indiana in 1892, the year Orie was born. This was the first of three annual Sunday school conferences where leaders rallied a new generation to “aggressive” and “progressive” programs of mission, charity, and service. To facilitate such ministries, MC and AM leaders enlarged the work of the Mennonite Evangelizing Board (1892); founded Elkhart Institute (1895), forerunner of Goshen College; and formed a binational denominational body, the Mennonite General Conference (1897). Though they had been in North America two hundred years, MC and AM congregations had organized only in regional conferences until now. The building of Mennonite institutions continued: the Mennonite Board of Education (MBE, 1905), Mennonite Board of Missions and Charities (MBMC, 1906), and Mennonite Publication Board (1908) were all established by the time Orie was sixteen years old.

Some thirty years ahead of the Mennonite Church, in 1860, a few South German congregations in the Midwest had linked with a Pennsylvania congregation to organize a general conference to facilitate missions, publication, and higher education. The General Conference (GC) of Mennonites, as it was named, was enlarged by Dutch-Prussian-Russian (and Swiss) immigrants who arrived in the 1870s, bringing a wealth of experience in building and managing such institutions in Europe.

Also among the 1870s immigrants were members of the more evangelical Mennonite Brethren (MB) Church, founded in 1860 as a renewal movement in Russia. At a time when MC membership was still skeptical of mission work, both GC and MB churches in the 1880s sent “foreign” missionaries to Native American groups in Indian Territory (Oklahoma). Both denominations soon established institutions to organize and promote higher education, relief, immigration, deaconess ministries, hospitals, charitable homes, missions, and publications. Most notably for the GC Mennonites was the founding of Bethel College in North Newton, Kansas (1887), and for MB adherents the establishment of Tabor College in Hillsboro, Kansas (1908).

John F. Funk, pioneer publisher and leader within the Mennonite Church, issued a clarion call to activism through his Herald of Truth and Herold der Wahrheit. He drew a new generation of awakened or “quickened” leaders to Elkhart, where his publishing enterprise was located, making the city a center of the new activism, a Mennonite expression of the Progressive Era.12 Funk, together with other church elders, built the stage on which Orie Miller would perform. They established the modern church institutions that he would multiply and manage with uncommon talent, efficiency, and discipline. Orie Miller later reflected that the work of their fathers had given him and Harold Bender, Goshen College dean and author of the seminal book The Anabaptist Vision, both a “home and church life advantage.”13

Orie recalled his father’s enthusiasm about his “contacts” in Elkhart, though occasionally he was also discouraged, even depressed, by church troubles. When returning from preaching at a mission or board meeting, D. D.’s experiences became the topic of family conversations. Church institutions and leaders became household names. Traveling missionaries and church leaders often dined and slept at Cloverdale Farm, the Miller family home. Occasionally, boards or committees gathered there to do their work. Orie long carried the vivid memory of a meeting where a churchwide music committee designed the Church and Sunday School Hymnal, published in 1902.14

THE SHAPING OF A FIRSTBORN

Orie (Ora) Otis was born on July 7, 1892, three years after D. D. and Nettie were married. Orie’s name was chosen to honor D. D.’s friend, colleague, and former schoolteacher D. J. Johns, who was also the bishop who ordained D. D. as deacon, minister, and later as bishop. In the five years before Orie was born, D. J.’s wife, Nancy (Yoder) Johns, bore two sons, one named Ora,15 and the other Otis,16 and the Millers called their firstborn after these two. It was a name Orie never liked—typically, he signed letters as “O. O. Miller.” Having begun the alliterative naming pattern, matching his own, D. D. (or was it Nettie?) continued the form, perhaps with a chuckle, in naming the rest of their sons: E. E. (Ernest Edgar), T. T. (Trueman Titus), W. W. (William Wilbur), and S. S. (Samuel Silas). The six daughters happily escape...