This is a test

- 342 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Ernest D. Martin takes Bible students into the rich text of the letter to the church at Colossae and the highly personal letter to Philemon. Martin draws on his experience as pastor, teacher, and writer to engage the reader in the complexities of the text. All the while, he focuses on a Christ-centered biblical theology and the amazingly revelant pastoral concerns that shaped these letters.

In commenting on Colossians, Martin highlights a wholistic Christology in contrast to the past and present perversions of the gospel. In the section on Philemon, he draws attention to the social implications of the koinonia of faith for the servants of Jesus Christ.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Colossians, Philemon by Ernest D. Martin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Teología y religión & Comentario bíblico. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Teología y religiónSubtopic

Comentario bíblicoColossians

A Letter Exalting Christ

Approaching Colossians

Students of Colossians are soon in for a surprise. How can one small, obscure, ancient letter be so potent? For many people, memorizing the names of the New Testament (NT) books involved the rote mastery of the sequence: Galatians, Ephesians, Philippians, Colossians. Colossians is the shortest of the four and for many persons the least familiar. However, one quickly discovers that Colossians is high- voltage material. Names, places, issues, and thought forms give evidence of it being written to a historically specific situation in the interior of Asia Minor. Yet this contextualized document has a way of spanning the centuries and cultures and yielding a powerful message for the modern church scene.

Cursory reading of the text reveals to us that Colossians is packed with words common to the vocabulary of biblical theology. With serious study we learn that Colossians touches on an amazingly broad range of topics. It also contains a number of more or less technical terms, the meanings of which are not obvious to the modern reader. As a result of his studies, William Barclay has said of Colossians, “There is no more difficult book in the New Testament” (1963:8).

The challenges, however, are more than balanced by the rewards of careful study. Colossians yields insights into the apostle’s pastoral way of confronting a potentially ruinous religious development. The church today is faced with movements and teachings that also challenge the sufficiency of divine revelation and power in Jesus Christ. Colossians is about Christ, although not an exhaustive treatise on Christology (an organized understanding of the person and work of Christ). However, the inclusion of this letter in the NT canon makes the church the beneficiary of the creative expression of one who was thoroughly convinced in mind and heart of the supremacy and sufficiency of the cosmic Christ.

One of Several Letters to Colossae

Two of the NT letters are written to Colossae, a city in the Roman province of Asia, in what is now Turkey. Similarities in mentioned circumstances and names link Colossians and Philemon to the same city and church community (see the introduction to Philemon). The most natural meaning of the reference to the letter from Laodicea (4:16) is that a third letter from Paul also came into the Lycus Valley and was passed on to be read at Colossae. Therefore, the church at Colossae (with the churches at nearby Laodicea and Hierapolis) is of more than passing interest to students of the NT. Colossae is on maps of first-century western Asia Minor because of two NT letters.

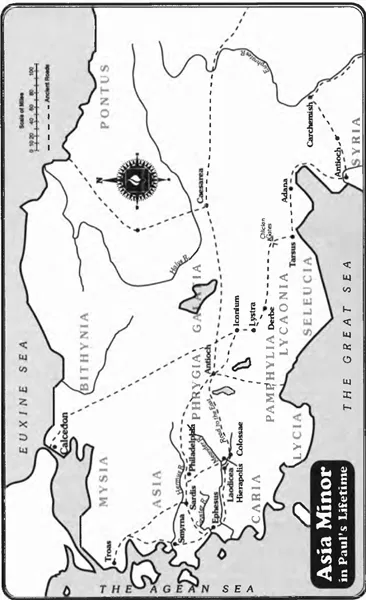

The map on the next page shows Colossae situated slightly south of a point 100 miles east of Ephesus and 135 miles west of Antioch in Pisidia. Note the rivers and major ancient highways, especially the important east-west route that went through Colossae and connected Ephesus (close to the Aegean coast), the cities of the Lycus Valley, Antioch in Pisidia, Iconium, Lystra, Derbe, Tarsus, Antioch in Syria, and points east in Mesopotamia.

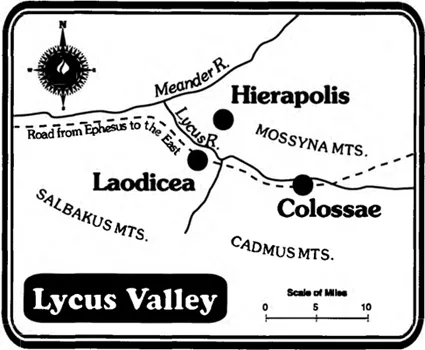

The now uninhabited location of ancient Colossae was discovered in A.D. 1835 by William J. Hamilton. The city had straddled the Lycus River about twenty miles upstream from where the Lycus River flows into the Meander River. Among other surface remains, Hamilton found ruins of the acropolis and theater on the south side of the river, and burial sites on the north side. The location of Colossae relative to the rivers and mountains and two other nearby cities on the Lycus River can be seen on the map of the Lycus Valley.

Several features of the Lycus Valley are of interest. Rich volcanic soil provided good grazing, and consequently a thriving wool industry developed. Colossae was known for wool dyed a deep red. The topography was marked with chalky calcium deposits and travertine. The area was subject to earthquakes. A major quake in A.D. 60-61 is known to have destroyed Laodicea. Less explicit evidence implies that Colossae and Hierapolis were also devastated at the same time. Laodicea and Hierapolis were soon rebuilt, but Colossae apparently was left in ruins, since later historical records do not mention it. This provides strong support for dating the writing of Colossians prior to that earthquake.

In pre-Christian times Colossae was the most prominent of the three Lycus Valley cities. Colossae is listed in the annals of Herodotus and Xenophon (both in the fifth century B.C.) as being a large, prosperous city. However, in Roman and Greek times Laodicea and Hierapolis surpassed Colossae in size and significance. Colossae may have been one of the least of the cities in which a church received a letter from Paul.

When the gospel came to Colossae, the populace was made up of a diverse cultural and religious mixture, including the indigenous Phrygian people, Greek settlers, and likely a significant Jewish population. Josephus records that in the early part of the second century B.C., Antiochus III transplanted two thousand Jews from Mesopotamia to the districts of Lydia and Phrygia (Ant. 12.147-153). A Roman governor in the Lycus Valley district intercepted a shipment of gold being sent to Jerusalem to pay the temple tax. Calculating from the amount, the Jewish population has been estimated to be as high as 50,000 (Barclay, 1975a:93). Colossae, being located on a major east-west highway, was undoubtedly a cosmopolitan city.

The religious landscape in the Lycus Valley was even more diverse. Research has identified Persian and other Asian religious elements as well as Roman and Greek religious ideas and practices. [Religions, p. 313.] A blending of various cultic beliefs and ceremonies is known as religious syncretism. Into just such a pluralistic cultural and religious environment, the gospel of Jesus Christ was proclaimed and was bearing fruit and growing (Col. 1:6).

The Church at Colossae

How and when the church began at Colossae is not clear. Neither Colossians itself nor Acts supplies an explicit account of the origin of the congregation. According to Colossians 1:7, Epaphras, not Paul, brought the gospel to Colossae. Yet Paul knew a number of persons in this church. The reference in 2:1 to those who had not seen him face to face could refer to new persons who came into the church later or mean that he had never been there.

Although there were Jews from Phrygia present on the day of Pentecost (Acts 2:10), the biblical record contains no hint that they took the gospel to the Lycus Valley. Acts 13:49 reports that “the word of the Lord spread throughout the region” (around Antioch in Pisidia). Because a major highway went from Antioch in Pisidia through Colossae, it is possible but not probable that disciples spread the good news as far as Colossae, 135 miles westward in the province of Asia. Reference to Barnabas (4:10) fits this option. Paul went through the region of Pisidia again on his second missionary campaign (Acts 16:6), but seems to have taken a northern route to Troas rather than the one through Colossae. On the third campaign the most direct route (but not the only one) from Antioch in Pisidia to Ephesus was through Colossae, but Acts does not indicate a ministry there (Acts 18:23; 19:1).

The most likely scenario is that during Paul’s three years at Ephesus (ca. A.D. 53-56), Epaphras, a native of Colossae who had become associated with Paul, introduced the gospel to the people of the Lycus Valley. If the reading on our behalf (1:7) is accepted [Text, p. 320], Paul may have been behind the evangelizing efforts of Epaphras. All this means that when this letter was written, the church at Colossae was probably not more than about eight years old, and perhaps younger. If, as the evidence suggests, life in Colossae came to an end with the major earthquake in A.D. 60-61, the congregation there was rather short-lived. Yet out of this small chapter in the story of the spread of the gospel, a letter has been preserved that is of immense value and interest for the Christian church universal.

Several details of the letter imply that most of the members of the church at Colossae were of Gentile background. For example, there is little reference to the Old Testament. Colossians 1:12, 21, 27 refer to outsiders (Gentiles) being brought in. Also, the vice lists in chapter 3 include sins associated with Gentiles more than with Jews. In most cities where Paul preached Christ, a few Jews responded along with Gentiles, and we assume that to be true also in the Lycus Valley.

The Author and His Circumstances

Traditionally the apostle Paul has been accepted as the author of Colossians (and Philemon). Except for occasional greetings in his own handwriting, the actual writing of all of Paul’s letters was probably done by a secretary. (See Rom. 16:22; 1 Cor. 16:21; Gal. 6:11; Col. 4:18; 2 Thess. 3:17; Philem. 19.) For Colossians, the secretary may well have been Timothy.

Pauline authorship of Colossians has been challenged along several lines. Analysis of the vocabulary reveals that Colossians contains thirty-four words not found elsewhere in the NT. Before jumping to conclusions about authorship, we also note that Galatians has thirty-one words not found elsewhere in the NT. Vocabulary differences are largely accounted for by differing subject matter. Similarly, we can readily explain differences of style in the letters attributed to Paul by taking into account that Paul had new matters to address and found new ways of expressing his responses. Along with elements of style peculiar to Colossians, many similarities of style are also found in comparing Colossians with the undisputed writings of Paul.

Based on the assumption that the false teachings addressed in Colossians come from Gnosticism, some say that a later date of writing is required because Gnosticism did not come into full bloom until the second century. However, that argument holds true only if full-scale Gnosticism is read back into Colossians. [Gnosticism, p. 289.] If what we have in Colossians are first-century ideas, some of which in time developed into Gnosticism, then Pauline authorship is not thereby a problem.

Certain interpreters contend that Colossians reflects a much more highly developed Christology than could have been the case in Paul’s time. But that conclusion presupposes a well-defined development of the doctrine of the person and work of Christ. Who is to say what Paul could or could not have understood about Christ at a given time? [History of Christology, p. 295.]

Although some scholars continue to consider Colossians as written by someone else in Paul’s name (deutero-Pauline), scholarly opinion seems to be moving toward greater acceptance of Pauline authorship. Philemon is almost indisputably Pauline. Colossians and Philemon are linked together in several ways, and these connections strongly favor Paul as author of Colossians. The lists of persons in the greetings of both letters are almost identical. Both mention similar circumstances of imprisonment, and both have Colossae as their destination. The self-evident authenticity of Philemon gives convincing support to the same authenticity for Colossians.

Paul was in custody when he wrote Colossians and Philemon (Col. 4:3, 18; Philem. 13). But which imprisonment? Where? Traditionally, commentators thought that four of the so-called prison epistles—Ephesians, Philippians, Colossians, and Philemon—were written during Paul’s first imprisonment at Rome. Philippians conveys an uncertainty about the future not found in the others. But the other three accord well with the circumstances of custody described in Acts 28:3...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Abbreviations

- Contents

- Series Foreword

- Author’s Preface

- Colossians

- Philemon

- Synthesis: The Letter to Philemon

- Outline of Philemon

- Abbreviations

- Essays

- Map of Palestine in New Testament Times

- Map of the New Testament World

- Bibliography

- Selected Resources

- The Author