![]()

1

THE FLOWS OF THE SLAVE TRADE

The scale of the transatlantic slave trade can only be estimated rather than calculated precisely. Over the past century numerous scholars have attempted to determine the extent of the trade, but their estimates have varied widely. Greater precision on this matter is more readily available today, however, than at any previous time. The collective research endeavour that has produced the online Transatlantic Slave Trade Database offers historians the most detailed opportunity ever available to analyse the flows of slaving in the Atlantic world. Dealing with the most important form of forced migration between continents in modern history, the database includes information on 33,367 voyages that embarked 10,148,288 slaves in Africa and on 33,048 voyages that disembarked 8,752,924 slaves, mainly in the Americas, between the early sixteenth and the mid-nineteenth century.1 This covers about 80 per cent of all transatlantic slave trade voyages.2 The compilers of the database calculated the overall volume of the slave trade from information on individual voyages and from inferences made from missing data to create estimates of the total transatlantic slaving traffic.3

The revised database provides historians with a firm basis for quantitative enquiries into the extent and characteristics of transatlantic slaving across time and space. The numbers matter because they provide the best estimates available of the contours of the slave trade, allowing the historian to pinpoint the importance of some national flags in transporting Africans against their will to the Americas and the peripheral nature of other flags. The database also provides statistics on fluctuations in the scale of the slave trade in different epochs and during wartime and peacetime. Only by contextualizing the flows of slaves according to these recently compiled data can the extent and persistence of transatlantic slaving be analysed in depth.4 This chapter uses the estimates in the revised database to discuss the distribution of the slave shipments according to national flags, the African region of departure, and the American region of arrival over the entire course of transatlantic slaving.

NATIONAL FLAGS AND THE SLAVE TRADE

The national flags that dominated the slave trade were the major Western European trading powers that competed with one another for overseas trade and empire in the early modern period: Spain, Portugal, France, the Netherlands and England. These nations had the financial resources and the commercial motivation to conduct long oceanic voyages. The slave trade formed just one line of commerce followed by vessels from these nations, and was closely connected to direct commodity trades between European ports, Asia and the Americas. The Africans supplied via the slave trade and the goods taken in direct commerce with American destinations were linked to the emergence and growth of a plantation sector that produced staple crops on agricultural estates for exportation back to the Old World. The major plantation staple commodities were sugar (pre-eminently), tobacco, rice, cotton and coffee. All these crops needed to grow in warm climates; they required a large labour force to carry out multifarious tasks including planting, harvesting and transporting the crop to ships.5 Staple crops grown on plantations catered for a strong growing market for tropical groceries among European consumers. Smoking tobacco, taking snuff, sweetening tea and coffee with sugar, and using sugar and rice in cooking, all advanced considerably as consumer products because of slave-grown commodities. Cotton, which only became a significant export crop after 1800, was the one major product among these staple commodities that was connected to clothing rather than to food and drink.6

In five cases – Portugal, Spain, France, the Netherlands, England – the ships involved in the slave trade conducted triangular voyages beginning in their home country, sailing out to Africa, buying slaves there, transporting them across the Atlantic for sale in the Americas, and then returning westwards to their original port of departure.7 In the case of the Brazilian slave trade, ships usually sailed on a bilateral basis between Brazilian ports and the west coast of Africa.8 Merchants in North America also organized slaving voyages, beginning while the thirteen colonies were part of the British Empire before 1776 and continuing after the formation of the United States. This, too, was a triangular trade, with ships sailing from North American ports to exchange goods in West Africa for slaves, who were taken to mainly West Indian destinations, and then a final leg of the voyage back to their North American provenance region. Denmark was the main smaller flag to participate in the triangular slave trade; other minor slave-trading polities included Sweden and Brandenburg/Prussia.9

THE FLOWS OF THE SLAVE TRADE

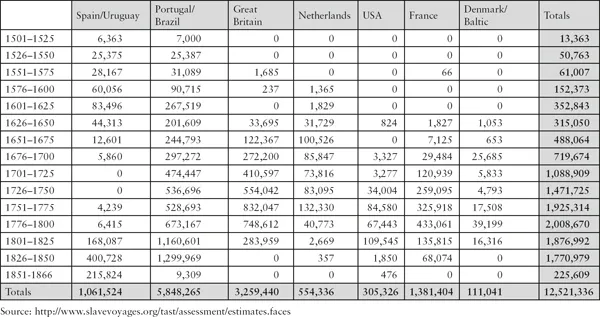

The flows of the slave trade were very modest in the sixteenth century: only 2.2 per cent of the embarked captives during the entire slave-trade era were placed on vessels before 1600 (Table 1). Transatlantic slaving voyages increased significantly from the second half of the seventeenth century onwards. They maintained high levels of slave shipment, amounting to 1–2 million embarked African captives in each quarter-century between 1701 and 1850: that was the peak period in which transatlantic slaving flourished. Table 1 shows the main contribution of national flags to the slave trade. The Spanish and the Portuguese (via the Luso-Brazilian trade) had the longest involvement with transatlantic slaving. Conquest and settlement by the Iberian powers in Central and South America and the Caribbean in the sixteenth century paved the way for the deployment of slave labour. The Spanish did not develop a plantation sector until the second half of the eighteenth century, while the Portuguese supplied slaves mainly for the Brazilian sugar industry.10 The Iberian powers continued to send slaves to their American territories until the end of the Brazilian and Cuban slave trades in 1851 and 1867.

Table 1: Slave embarkations by flag, 1501–186611

Table 1 shows that the Iberian powers were responsible for 55.2 per cent of the embarked slaves taken across the Atlantic between 1501 and 1866.12 The leading Iberian ports in the trade were Lisbon, Bahia, Recife and Rio de Janeiro.13 The volume of the Portugal/Brazil trade was especially large in the nineteenth century: four out of every ten Africans taken by that national flag to the Americas were sent between 1801 and 1866. Table 1 shows that Portugal/Brazil embarked many more slaves than Spain/Uruguay. A caveat needs to be registered, however, about this. Until 1789 Spain pursued a policy of asiento agreements whereby other countries were licensed to carry slaves to Spanish America. The Spanish and Portuguese crowns were unified for sixty years after 1580. Portugal held the first official asiento from 1595 until the Portuguese revolt against Spain in 1640. Thereafter asiento holders included the Netherlands, France and Britain. Whereas it was once thought that Spain largely relied on these trading partners to take slaves to Spanish America, recent research has found that ships sailing under the Spanish flag also conveyed large numbers of captives to Spain’s colonies.14

England, the Netherlands and France played a minimal role in the flows of the slave trade in the sixteenth century. Each of these nations sent out voyages of exploration to the Americas before 1600, but none of them had yet settled significant colonies across the Atlantic. The establishment of colonies by these powers during the seventeenth century led to the emergence of a significant slave trade for each of these flags. England colonized much of the east coast of North America in the seventeenth century and acquired a number of Caribbean islands. France and the Netherlands also settled colonies in the West Indies during the seventeenth century, with the Dutch gaining an important foothold in territories (Demerara, Essequibo, Berbice and especially Suriname) on the ‘wild coast’ (as they termed it) of the northern end of South America. England carried the largest volume of slaves of these three powers. This reflected the fact that Britain acquired much more territorial acreage in the Americas than her northern European rivals, allowing scope for a larger plantation sector: by c. 1775 the British Empire in the Americas covered more than twice the square miles of the Dutch and French Atlantic empires combined; and the French and Dutch colonies in North America and the Caribbean had only a quarter of the British population in the same regions.15

The British slave trade grew in the last four decades of the seventeenth century and reached its peak during the eighteenth century: between 1660 and 1807, when Britain abolished its slave trade, vessels sailing from English ports to North America and the Caribbean embarked more than three million slaves (Table 1). Britain was the leading slave-carrying nation in the eighteenth century.16 London was the main English slaving port from the mid-seventeenth century until around 1720, when the English branch of the trade lay mainly under the auspices of the London-based Royal African Company.17 But after the British slave trade was opened to non-chartered companies in 1698, Bristol’s private merchants challenged London’s position in the trade to assume dominance among British slave-trading ports in the 1720s and 1730s.18 Liverpool overtook Bristol and London to become the leading port in the British slave trade between 1740 and 1807. During that period, Liverpool became the busiest port in the world for dispatching slaving voyages. Its merchants effectively drew together the human capital needed to conduct the slave trade successfully.19

British North American colonial shipping contributed to slave trade flows during the eighteenth century, notably from Rhode Island. Newport became the main North American port connected with transatlantic slaving, assuming greater importance than the much larger port of New York. Newport’s merchants had good commercial connections in the Caribbean but had the added advantage of having a cluster of rum distilleries in Rhode Island – using molasses from the West Indies as their main ingredient – to supply alcohol to West African traders in return for slaves.20 After the American Revolution, a slave trade from the United States embarked nearly 177,000 slaves in the half-century after American independence (Table 1). Most of these were delivered via Charleston, South Carolina to southern US markets before the abolition of the African slave trade to the United States in 1808. Thereafter American vessels supplied slaves to colonies of other powers in South America and the Caribbean; in some cases, this meant deploying American vessels in illegal slaving ventures.21

The French slave trade always had a smaller volume than the British slave trade in each quarter-century covered by Table 1, but French merchants still embarked 1.38 million slaves during the entire period of transatlantic slaving – an 11 per cent share in the trade. As with Britain, the eighteenth century was the peak period for the French slave trade. In 1794 France abolished slavery in all its possessions, but Napoleon, when ruler of France, restored slavery in territories growing sugar cane in 1802. The French slave trade was outlawed in 1815 but continued until 1831, with the French flag sometimes being used illegally thereafter. French transatlantic slaving declined significantly in each quarter-century after 1800, but still carried 17,000 slaves annually in 1820–5, a figure matching the numbers of the 1770s (Table 1).22

Nantes dominated the French slave trade, accounting for more slaving expeditions than the combined share of its rivals – Le Havre, La Rochelle, Bordeaux, St Malo and Honfleur. Nantes, situated near the mouth of the Loire River about thirty miles from the French Atlantic coast, was well placed geographically to participate in transatlantic slaving ventures. Nantais merchants accounted for 42 per cent of the Africans dispatched on French vessels in the eighteenth century.23 On the eve of the French Revolution, the Nantes economy relied on the slave trade. Between one-third and one-half of all tropical produce entering Nantes at that time comprised payments for slaves acquired from Nantais merchants.24 Between 1813 and 1841 Nantes embarked 102,000 slaves, concentrating...