![]()

CHAPTER 1

HISTORIOGRAPHY

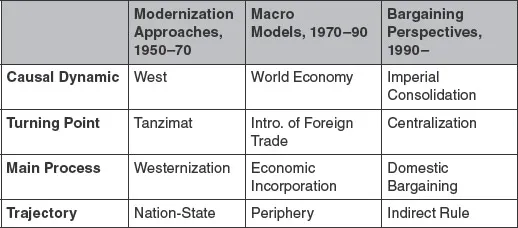

There have been three waves of late Ottoman historiography since the second half of the twentieth century. Each rose to prominence in a different global context, maintained almost complete hegemony for two decades, and was later replaced by an upcoming intellectual current. Changing historical approaches also meant that the field of Ottoman Studies enjoyed distinct thematic choices, frameworks and methodologies which were in line with worldwide trends in historiography.1 It will be my argument here that the three episodes of late Ottoman history writing can be classified as modernization approaches, macro models and bargaining perspectives.

Modernization approaches were extremely influential in understanding top-down political change in the late Ottoman context. They set the tone for and confirmed the pre-eminent position of political, intellectual and diplomatic history in Ottoman Studies. Focusing on world economy, macro models pushed the Ottoman Studies towards dependency and world-systems perspectives and introduced social and economic history to the field. Bargaining perspectives have unseated modernization and global capitalism as the key variables in understanding the late Ottoman Empire. Inspired by institutionalism, postcolonial analysis, and micro-history studies, the new scholarship turned the attention to state and society relations and promoted a negotiation model to explain the Ottoman past.

This chapter reviews the historiographical trends in late Ottoman Studies by a comparative discussion. I will do this by unpacking each wave around the same analytical questions. My analysis will demonstrate that the Ottoman scholarship associated with each wave has a different idea when it comes to locating the macro-historical dynamic, identifying the turning point, registering the main process, and projecting the ultimate direction in Ottoman history. As a helpful short cut, Figure 1 summarizes the evolution of late Ottoman historiography, the main arguments of each wave, and the major differences among them.

Four caveats are in order for the discussion below. First, I do not evaluate each wave on a purely theoretical basis but rather focus on its reflection in late Ottoman Studies. Second, my analysis favors the common ground in each wave that is neither all-inclusive nor oriented towards a single study. Third, the fact that each wave is considered to be hegemonic in a certain time frame does not necessarily mean that studies of the same genre stopped appearing afterwards or lost credibility in a dramatic fashion. Finally, there have always been synthetic works that combine a variety of waves, approaches and agendas of late Ottoman history writing.2

Figure 1 Three Waves of Late Ottoman Historiography

Modernization Approaches

Modernization approaches entered the Ottoman field after the institutionalization of area studies in post-war America. Cold war and decolonization played a critical role in this transformation. Both historic events confirmed the universal credentials of Western development and provided a favorable political environment to replicate that experience in the non-Western world. Around the same time, anthropologists and political scientists were documenting the momentous steps taken towards national integration, reaffirming the belief that the nation-state model was desirable and working for the rest of the world. Historians of the Middle East followed suit.3

The major impact of post-war world order on Ottoman historiography then was to put Western experience at the center of analysis. As Bernard Lewis aptly put it, the story of the Middle East and the Ottoman Empire should be told as the Western impact and the domestic response to it.4 The historical dynamic that turned the Ottoman world upside down was the economically advanced, technologically superior, and culturally dominating Western world. Departing from the earlier conclusions of military historians though, modernizationists viewed the West as a civilizational asset with universal nature. In this view, the West was to be emulated and drawn upon to arrest imperial collapse.

With this perspective in mind, modernization authors put special emphasis on episodes of top-down imperial transformation. Accordingly, the proclamation of Tanzimat (1839) became the most credited event in late Ottoman historiography.5 By creating a modern bureaucracy, building a new economic infrastructure, and strengthening cultural ties with the West, Tanzimat is seen as the landmark event that allowed the Ottomans to embrace Western modernity.6 Earlier reform efforts of Selim III and Mahmut II are also noted as key moments of change and received justification for expanding the modernization ideal.7

The unveiling of a reformist thread produced a cyclical understanding of late Ottoman history. While the Ottoman state was moving towards progress and civilization, the undercurrent would be a reactionary backlash. Every major Westernizing reform was to be followed by a conservative reaction. The reformist Sultan Selim III was killed by a “mob” that opposed his new ways; the Tanzimat period was followed by the reign of the absolutist Abdulhamid II; and the Second Constitutional Period (1908–1918) was threatened by an Islamic upheaval in the capital city. Presenting late Ottoman history as a struggle between Westernizing reformers and conservative forces, first-wave authors endorsed the agenda of the former group.

That political agenda was modernization, which was believed to be the most critical process in late Ottoman history.8 Synonymous with Westernization, it was top-down in format and bureaucratic in nature. Imperial reforms in the fields of higher education, administration and the military were highlighted to make the case that the Ottoman experience began to converge with the historical development of the West. Subsequently, the grand narrative of late Ottoman history turned into a list of achievements towards establishing state-led modernity, giving disproportionate attention to the secularization of education, modernization of bureaucracy, and Westernization of public life.9

Confusing legislation with implementation and state transformation with societal practice, the modernization school found a political agency to be named as vanguards of Westernization. This was the burgeoning bureaucratic class. Graduated from modern schools and blended with Western ideals, reformist intellectuals and army officers are thought to be a class in themselves. Belonging to the universe of ‘middle class’ revolutionaries at the turn of the century, they were better organized than their Iranian counterparts and had more access to state institutions than their Russian contemporaries. The Ottoman reformists were then assigned a historic mission: to save the Ottoman state from political collapse and transform Turkish society via a top-down Westernization project.10

With bureaucratic agency in charge, modernization historians were ready to announce the ultimate direction in Ottoman–Turkish history: to reach the level of (Western) civilized nations. This was the main historical outcome of interest. In fact, to the surprise of modernization historians, this is exactly why this type of history writing is not historical but rather theory-driven.11 The idea is to explain the successful modernization of the Turkish nation–state by reconfiguring the Ottoman past. As such, late Ottoman history served an ideological purpose with no independent narrative of its own; that is, to provide a selective background to the emergence of modern Turkey.12

Military strengthening. The First Battalion of the First Infantry Regiment of the Imperial Guard.

Nonetheless, first-wave scholarship was fully aware that the Westernization project of the bureaucratic class was not the only political option on the imperial agenda. There were ethno–religious and regional interests throughout the empire, and rival perspectives took hold in the palace and among the ranks of Ottoman bureaucracy. The modernization school viewed these multiple sites of opposition as a threat to imperial existence and named them a reactionary front. The opponents of bureaucratic transformation were blamed in particular for blocking the path to modernization and progress and keeping the empire backwards. At this point, political opposition and cultural dissent acquired a regime-threatening and trajectory-shifting meaning in the modernization discourse.

Political opposition operated at two levels in the analysis. First, top-down reforms create resentment and alienation with the ‘ignorant’ masses and the self-interested provincial elite. This type of social reaction was shown with reference to the Tulip Era, the Tanzimat period, and the Second Constitutional Revolution.13 Second, as Niyazi Berkes formulated it very cogently, ideological rivalries divide the imperial elite into two camps, as reformists and traditionalists.14 From a modernization standpoint, the worst-case scenario was the building of alliances between the two layers of opposition, which would destabilize the state and threaten the Western trajectory. The best-case scenario required the purging of conservatives from the upper echelons of the state and securing a trouble-free periphery with quiescent masses.

One of the innovative arguments of the (later) first-wave studies then was to introduce intra-elite tension and center-periphery conflict as the key elements of regime change in the Ottoman Empire. Both instances represented fundamental disagreements about the content of the state which were fought over (the scope of) Westernization. Hence, the more the Ottoman–Turkish state was Westernized, the weaker it became in the eyes of its subjects.15 Consequently, the modernizing Ottoman–Turkish state lost its legitimacy in society, turned Islam into an ideological shield of the periphery, and created a major divide among the ranks of the political elite. Şerif Mardin thinks that this type of public alienation started in the final years of the late Ottoman Empire and accelerated with the founding of the Turkish Republic.16

Overall, modernization accounts provided us with a mono-causal explanation about political change in Ottoman history. Late Ottoman history came into motion with Western impact and became a derivative story about the defensive modernization of the imperial state.17 Periodization choices, state-centered analysis, and the evolutionary idea of becoming a modern society were based on a selective and ideologically-catered reading of Ottoman history. We are told over and over again that top-down modernization is the only successful project on political change and state formation in the Third World, reflecting the teleological vision and universal bias of the modernization school.18

Modernization approaches left a huge deal of late Ottoman history outside. Even the key story of imperial reforms which was at the heart of the modernization narrative was covered via legislation attempts in Istanbul, leaving the larger question of state-society relations missing in the analysis. Pre-occupied with high politics in the capital, there was no room for a spatial perspective in the modernization analysis.19 As such, the major problem with this approach is that it ignored the diverse record of imperial subjects across the Ottoman territories and assumed its convergence along modernization lines towards the end of the century.

Two other points are worth mentioning that will open up the discussion to the macro models in late Ottoman historiography. The first point is about the content of modernization. By attaching modernization to Westernization and Ottoman state practices, first-wave authors presented a restricted version of Ottoman modernization. Not recognizing a public sphere outside the realm of the state, modernization views were silent about the ways in which social classes, families, religious communities, provincial elite, and the janissaries neg...