![]()

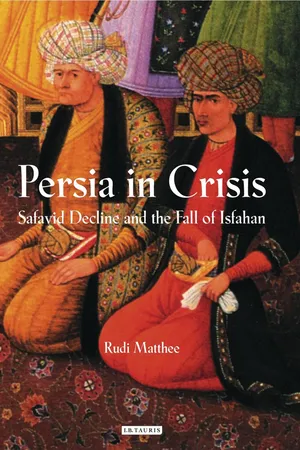

Chapter 1

Patterns: Iran in the Late Safavid Period

It is thus clear that royal justice has nothing to do with rectitude and the absence of causing harm. Some harsh policies of rulers generate security; and much of the blood-letting they engage in prevents people from unjustly shedding other people’s blood and, for fear of retribution, keeps them from killing others.

Findiriski, Tuhfat al-`alam, 128

In forgiveness there’s a pleasure which doesn’t exist in revenge.

Nawzad, Namah’ha-yi Khan Ahmad Khan, 94

INTRODUCTION

Several features of the late Safavid state make it appear as a west Asian example of the early modern state. Its rise in the early sixteenth century was fueled by tribal military power, charismatic leadership, and religious messianism. Over time, these forces grew weaker, to be replaced or supplanted by new sources of support and legitimacy. As the ruler’s divine aura faded and the chiliastic enthusiasm of his followers abated, a more scriptural form of religion espoused by a newly formed clerical class came to replace it; as the Qizilbash, the Turkoman warriors (descendants of the Ghuzz Turks who had invaded the eastern Islamic world in the tenth/eleventh century) who had brought the Safavids to power, proved to be an unruly and destructive force, a new military and administrative elite was brought in and groomed to neutralize them. Over time these changes generated an urban-based system of governance blending traditional patterns of Iranian-Islamic kingship and institutionalized religion.1

These changes notwithstanding, the Safavid state remained a premodern formation along Weberian, patrimonial-bureaucratic lines, and not just because Iran did not undergo the social disciplining that set some contemporary European societies on the road to (bureaucratic) modernity.2 The state endured as an extension of the royal household, its administrative offices knew little functional division, and private and public spheres overlapped. Coercive power, in sum, continued to be the ruler’s personal property.3

This represents reality only up to a point, though. A common criticism of Weber’s theory is that it presupposes static, even immutable structures. Weber was explicit about the fragility of patrimonial rule, yet he formulated state and society as a unitary system and, in his nineteenth-century (German) tendency to overrate the ability of the state to control, manage, and arbitrate, he paid insufficient attention to societal challenges to its power. Michael Mann’s reformulation of Weber’s ideas, taking this into account, rejects a simple antithesis between the all-powerful state, and society, the populace, the objects of its coercion. Mann sees a dialectic relationship between the two, a relationship in which a “range of infrastructural techniques are pioneered by despotic states, then appropriated by civil societies (or vice versa); then further opportunities for centralized coordination present themselves, and the process begins anew.”4 He also views society less as a structure than as a series of “multiple overlapping and intersecting sociopolitical networks of power.”5 This study follows these propositions, including Mann’s distinction between “despotic” (immediate) and “infrastructural” (logistical) power.

It is useful to broaden Weber’s conception of the patrimonial state even further by emphasizing the tributary dimension of relationships.6 Power relations in Safavid Iran were fueled by zar-u-zur, gold and force, monetary inducement coupled with coercion including violence. The latter—military force—was the more important of the two. The shah was first and foremost a warrior-in-chief, the head of a band of fighters, and violence, or the threat of violence, was what made his opponents retreat or submit, and it was always the means of last resort for the state. Following Walther Hinz’s focus on idealist—ideological and religious—pursuits in his analysis of the rise of the Safavids, we have perhaps paid too much attention to ideology and not enough to the more mundane motives of the warrior band that carried the Safavids to success—booty, a lust for power and glory, and the manly urge to conquer and subdue.7 Effective and lasting power, however, could only be secured by way of tributary relationships involving the exchange of money. This, in turn, presupposed negotiation, resulting in a dynamic interaction between state and societal groups. Not just political domination but all forms of surplus extraction in Safavid Iran, from regular taxation to rent and confiscation, from state monopolies on commodities to forced partnership, were the outcome of bargaining processes pitting central power and its quest for domination against local resistance and subterfuge. Tributary relations were primarily extractive, applied to state centralization. But, following ancient patterns, they also knew a reciprocal, redistributive element.8 Extraction could only be legitimate if balanced by the spread of resources and power among the members of the ruling clans. Only thus could (temporary and instrumental) loyalty and cooperation be expected.9

The Safavid state became centrally organized, but it was never able to overcome the political, social, and economic fragmentation of society. Its leaders naturally pursued maximal administrative and fiscal control. Shah `Abbas I’s policies, most notably his efforts to replace tribal power with a new military and bureaucratic elite and his choice of Isfahan as the realm’s administrative and economic center, represented a major step on the road from a tribal nomadic to an urban sedentary order. Despite all efforts, however, the Qizilbash warrior, the mainstay of the Safavid army, never became fully subordinated to the urban scribe, the pillar of bureaucratic management and order. The ancient tribal tradition, decentralized, exploitative, redistributive, and built on corporate legitimacy, continued to challenge its urban-based, agrarian Iranian counterpart, with its tendency toward accumulating revenue and concentrating power in the hands of a single supreme ruler.10

ANALYZING SAFAVID SOCIETY

This opening chapter presents Safavid Iran as a set of tensions. Some characteristics of its state and society enhanced order, cohesion, and stability, while others fostered fission and fragmentation. The purpose of this approach is to move away from a simple dichotomy between state and society as well as to dispel the idea that the state controlled society. We may blame long-standing Western notions of Oriental despotism for this as much as the Persian-language sources with their tendency to portray a state fully in charge of society—with a divinely ordained ruler at the head of a bureaucratic apparatus administering appointments and collecting large surpluses, and armies patrolling a well-defined territory. Once we collate these highly stylized sources with other, more realistic documentation and view the country in its proper environmental and political-historical context, a different picture emerges—one of a minimalist state masquerading as an absolutist court, highly factionalized, limited in its ability to collect information, dependent on fickle tribal forces for military support, and forced to negotiate with myriad societal groups over power and control.11 The shah’s power was awe-inspiring and Safavid ideology was a commanding force, but state absolutism was a relative concept and centralization was at best uneven. Like Mughal India, Safavid Iran was a “strange mix of despotism, traditional rights and equally traditional freedoms.”12

CENTRIFUGAL FORCES

Physical and economic aspects

It took Iran much longer than most other parts of the Middle East to form a strong central state. Well into the twentieth century concentrated power faced formidable obstacles, with a harsh natural environment, causing communication to be slow and difficult, in first place. Iran’s heartland, the plateau, is made up of vast stretches of semi-desert and piedmont terrain flanked by formidable mountain ranges—a saucer, Chahriyar Adle calls it. Human habitation, irrigated agriculture, and the traffic of people and goods have always clustered on its rims, the triangle that connects Mashhad with Tabriz via Tehran and that swerves south to the cities of Kashan, Isfahan, Shiraz, Yazd, and Kirman.13 The western Zagros range constituted a natural barrier against attack from the Mesopotamian alluvial lowlands, but the same mountains also impeded access from the country’s heartland to Kurdistan and Luristan, in addition to weakening the hold of the central state over ultramontane `Arabistan (modern Khuzistan), and making lasting control over Iraq nearly impossible. The northern Alburz range, separating the central deserts from the lush Caspian forests, in turn hampered communication between Isfahan and the silk-producing areas of Gilan and Mazandaran. All this was made worse by the fact that, unlike Europe, Russia, and India with their profuse waterways, Iran barely has any navigable rivers. This resulted in scattered villages, economic isolation, and affinities and loyalties that were intensely local and regional.

Perhaps the most important geographical distinction in Safavid times, dictated by climate, cultural particularism, economic orientation, and military concern, was the “inner frontier” that separated the north and the south, especially the Persian Gulf littoral, the “hot lands,” Garmsir(at).14 Ethnic, linguistic, and economic ties bound the north and the northwest to Anatolia and the Caucasus, and northeastern Khurasan to inner Asia. Of Kurdish origin, the Safavids hailed from the Turkish-speaking highlands of Anatolia; Tabriz and Qazvin had been their early capitals. Their military supporters, the Qizilbash tribes, had their origins and grazing grounds mostly in the same region. Georgians and Armenians, two groups that came to play a crucial military, administrative, and commercial role in Safavid society, had northern roots as well. Military challenges, too, tended to come from the northeast, the frontier with the Uzbeks, and the northwest, where the Safavids faced unruly mountaineers such as Kurds and Lezghis as well as the formidable Ottoman armies.15 Much of the country’s agricultural resource base was located in fertile Azerbaijan and the silk-producing Caspian provinces. All these factors made northern Iran a natural focus of Safavid attention and concern.

The southern littoral, by contrast, was alien territory for the Safavids. Its weather, swelteringly hot and humid for most of the year, must have been repellent to warriors used to the bracing climate of the high plateau. Most of its land was barren and unproductive. Ethnically and linguistically, too, the Garmsir was cut off from Iran’s interior; many of its inhabitants were Arabs, with a sprinkling of Hindus from Gujarat and Sind; the region interacted with semi-autonomous Basra and the Arab shaykhdoms across the water as much as with Iran’s heartland; its economy was oriented toward Oman—which received most of its food from Iran—and, most importantly, toward the Indian subcontinent.16 Emblematic of this orientation is the distinct currency, the larin, a coin that was current throughout the Persian Gulf basin and in the Indian Ocean as far as Ceylon and the Maldive islands.17 Aside from Fars, no part of the south ever elicited any special interest from the royal court other than for the revenue it produced. For all his concerns about trade, and despite the fact that he incorporated Bahrain and parts of the Gulf coast into his realm, even Shah `Abbas I himself is hardly an exception to this rule. He traveled a good deal during his long years in office, yet none of his campaigns ever took him beyond Shiraz.18 Instead, he spent much time in Mazandaran, the region from which his mother hailed, which he loved, and where he built the two resort towns Ashraf and Farahabad. His successors were no different, except that they paid even less attention to the south. They, too, often spent their winters in the lush Caspian region, hunting and relaxing. Otherwise they might go on pilgrimage to Mashhad or Qum. Armed expeditions to the south were rare, and the Safavids never really developed a solid military connection with the Gulf. Even the growing seaborne threat by the Omani Arabs at the turn of the eighteenth century did not inspire them to build a navy. The minor role the Garmsir played in the Safavid imagination is well illustrated in the way the region is represented in the seventeenth-century geographical compendium Mukhtasar-i mufid, which has the Persian Gulf littoral in last place.19

Economic realities arising from geopolitical conditions were a major cause of weak infrastructural state control. As a productive and consumer market, Safavid Iran was of modest size. Overwhelmingly arid, the country was poorly endowed with arable land and low in population density. Jean Chardin reckoned that barely one-twelfth of Iran was cultivated.20 According to the most plausible estimate, its population in the early to mid-seventeenth century did not exceed 8 million.21 About a third of those, moreover, were pastoralists, people who, living at the near-subsistence level, made only a modest contribution to the country’s economy. Safavid state income in the seventeenth century tells the story. Combined state and crown revenue is generally given as somewhere around 700,000 tumans, or no more than one-tenth of a tuman per inhabitant. Less than 200,000 tumans of this was crown revenue.22

The absence of significant gold and silver deposits was especially significant in this regard, since it made Iran dependent on the outside world for bullion and coinage. Other sources of wealth did exist, but few could be relied on for a sustained productive yield. Agriculture, heavily dependent on irrigation in most parts of the country, required intensive initial investment as well as high maintenance expenditure. Some of the empire’s richest agricultural regions eluded central control. Fertile plains around major cities such as Tabriz, Qazvin, and Isfahan ordinarily produced enough to feed the urban areas and their surroundings. Wheat and barley were grown throughout the country, even on the Persian Gulf coast.23 But some of the most productive areas, among them Shirvan, Azerbaijan, and the Caspian provinces, were situated on the periphery of the country and thus dangerously exposed to unrest and attack. The entire northwest faced Ottoman and, ultimately, Russian aggression. The inaccessible interior of heavily forested Gilan and Mazandaran had repelled land-based invaders since the seventh-century Arab conquest, but the Caspian littoral, where most of Iran’s silk was grown, was open to seaborne Cossack raids.

Iran’s low production of goods for which foreign demand existed combined with its scarce precious metal deposits gave it a peren...