![]()

CHAPTER 1

Considering Kabylia

The object of this study is the ensemble of political arrangements which the populations of the mountains of Greater Kabylia in northern Algeria contrived in the pre-colonial period for the purposes of governing themselves as sovereign communities independent of the central power, the Ottoman Regency of Algiers. These arrangements have been discussed over the years by many other authors in numerous works. I am presuming to add a further book to this literature because, dissatisfied with the understandings of these matters that have been in circulation to date, I wish to propose a new interpretation of the nature of the Kabyle polity in the pre-colonial period and an explanation of its genesis.

The analysis of the political organisation of pre-colonial Kabylia is a matter of considerable confusion. It is my conviction that this confusion arises from two main sources, the lacunae in the analyses of the French colonial ethnographers, notably Hanoteau and Letourneux and Masqueray,1 and the decision of more recent scholars to abandon what was valid in the work of their nineteenth-century predecessors and to substitute theoretical models that are less able than those they supplanted to do justice to the Kabyle polity. The rest of this book undertakes to make that case by dealing with the lacunae in question and thereby resolving the outstanding difficulties in the analysis of the political organisation of pre-colonial Kabylia, so that the constitutive principles and inner logics of the Kabyle polity of the later Ottoman period may at last be fully understood.

Greater Kabylia

The region called, in French, la Kabylie owes its name to the corruption of the Arabic word qbā’il. A plausible interpretation of this derivation identifies it with the plural of qabīla, an Arabic word conventionally translated as ‘tribe’, so that el-qbā’il designated ‘the tribes’ as distinct from the supposedly non-tribal or de-tribalised populations of the towns and their immediate environs. A more speculative interpretation suggests that the word is derived from the Arabic verb qabila, meaning ‘to accept’, so that el-qbā’il designated rather the people who ‘accepted Islam’ – that is, the indigenous Berber-speaking inhabitants of North Africa who were converted to the faith of their Arab conquerors. Both interpretations have been current in Algeria and Kabylia in recent times, although it should be noted that the word qabīla appears in the Kabyle language, in the Berber form thaqbilth, to refer to the largest unit of political organisation, which the ethnographers have rendered by ‘confederation’, a fact which favours the first interpretation above.

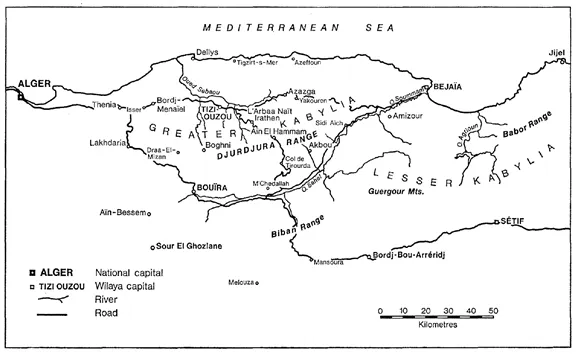

Map 1.1: The Kabylias.

‘Berber’ is primarily a linguistic term of classification, indicating those who speak one of the Berber dialects as their mother-tongue. Since the rise of the Berberist movement in the 1980s, the term amazigh (literally: ‘free man’; plural: imazighen) has become the fashionable (Berber) term to apply to all things and persons that are Berber. It was previously used to indicate the Berbers of the Middle Atlas and the Central and Eastern High Atlas in Morocco and was not in general use in Algeria.

It was the French who reserved the term ‘Kabyle’ to refer principally if not exclusively to the inhabitants of what is now known as ‘la Kabylie’. It appears that el-qbā’il was used by the townsfolk of pre-colonial Algeria to indicate all hillsmen without distinction, a practice that survives in some places.2 Otherwise, in Algeria today, ‘Kabyle’ refers to the Berber-speaking inhabitants of that part of the Tell Atlas, the coastal chain, that extends from the edge of the Mitija plain south-east of Algiers to the Babor mountains south-west of Jijel. The small Berber-speaking population of the Chenoua massif west of Algiers used to be called ‘les Kabyles du Chenoua’ but are now usually referred to by their Berber name as the Ichenwiyen. Other Berber-speakers in Algeria are known by other names, notably the Mzabis of the northern Saharan region known as the Mzab and the Tuareg of the Ahaggar and the Tassili n’Ajjer mountains in the far south, while those of the Aurès and Nememcha mountains in eastern Algeria and the high plains immediately to their north are known as the Chaouia, an Arabic word meaning ‘shepherds’ or ‘sheep people’. Thus the range of reference of the word ‘Kabyle’ has steadily been reduced and its focus sharpened. It is not clear when the contemporary usage became established but it certainly predates the French conquest3 and the inhabitants of what is now known as la Kabylie or, in Arabic, Bilād el-Qbā’il, have long referred to themselves as Leqbayel (singular: Aqbayli) and to distinguish their dialect of the Berber language from others by the term Thaqbaylith.

Strictly speaking, there are two Kabylias, Greater and Lesser. The population of the former is almost entirely Berberophone while in the latter both Berber- and Arabic-speaking populations are present in roughly equal proportions. Most authors further distinguish the Berberophone districts of Lesser Kabylia, consisting of the Soummam valley and the Biban, Guergour and Babor mountains from the Arabophone region to the east of the Wad Agrioun – that is, the mountainous hinterland of Jijel, usually referred to as ‘la Kabylie orientale’. This study is primarily concerned with the region known as la Grande Kabylie (in Arabic: el-Qbā’il el-kubrā), the mountainous country to the east of Algiers, bounded by the Mediterranean to the north and the Jebel Jurjura to the south and divided from la Petite Kabylie by the main ridge of the eastern Jurjura and its north-easterly extension in the lesser ranges of the Akfadou district.4

The region is extremely mountainous, dominated by the grandiose summits of the Jurjura, which attains a maximum altitude of 7,500 feet (2,308 metres) with the peak of Tamgout n’Lalla Khedija. Inhabited by Berber-speaking arboriculturalists and petty craft manufacturers for as long as anyone can remember, more densely populated than any other part of the Maghribi countryside, famed for its tradition of political independence, it has long attracted the attention of scholars, journalists and other observers. These include the imposing trio of Ibn Khaldun, Karl Marx and Émile Durkheim and, more recently, the – also imposing – duo of Pierre Bourdieu and Ernest Gellner. It has also produced its own chroniclers and numerous Kabyle and other Algerian writers have contributed, in increasing numbers in recent decades, to the endless debate on the region, its people and its traditions.

The Kabyles and the other Algerian Berbers

The Berber-speakers of North Africa do not possess a common territory or a common economic life and there is much variation between them in cultural and even linguistic terms. In Morocco, there are three main Berber dialects, those of the Chleuh of the south-west, the Imazighen or Berraber of the centre and south-east and the Rifians of the north,5 and there are other cultural differences between their respective speakers. In Algeria, the dialects of the Kabyles, the Chaouia, the Mzabis and the Tuareg are all distinct. Tamahaq, the dialect of the Tuareg, is not intelligible to the other groups and, although Kabyles and Chaouia may understand each other’s speech with relative ease, there is a noticeably greater Arabic influence in Thachawith than there is in Thaqbaylith.6

There are also religious differences. The Kabyles, the Chaouia and the Tuareg are all Sunni Muslims of the Maliki rite, but the Mzabis are Ibadis, adherents of a dissident sect whose only other North African members are to be found in the Berber-speaking populations of the island of Jerba off Tunisia and the Jebel Nefusa in Libya. More recently, religious differentiation of a kind has developed between the Kabyles and the Chaouia. The latter were strongly influenced by the Islamic Reform movement of Sheikh Abdelhamid Ben Badis and the Association of the ‘ulama in the 1930s and 1940s,7 whereas this had a more limited impact in Greater Kabylia.

Thus it is a mistake to speak of a Berber community as such in North Africa as a whole or even in Algeria as a whole. But there is a Kabyle community. The Kabyles possess a common language, a common territory and a common culture and they have long been conscious of this fact. They also differ from the other Berber populations of Algeria in several important ways.

First, the Kabyles are by far the largest of Algeria’s Berber populations. The 1966 census gave the Kabyle population as numbering 1,180,000, compared with approximately 400,000 Chaouia, 60,000 Mzabis and 15,000 Tuareg, but these figures undoubtedly underestimated the Berberophone element of the Algerian population at that time, assessing it in all at 17 per cent of the total. Subsequent censuses have not differentiated between those who speak Berber as their mother-tongue and those who do not, but it is now generally admitted that Berber-speakers make up between 20 and 27 per cent of the total population. Since this stands at 38 million today (2013), we can estimate there to be between 7.6 and 10.3 million Berbers in Algeria and in the Algerian diaspora abroad, of which between 5 and 7 million are accounted for by the Kabyles.

Second, they are not at all remote from the national capital, Tizi Ouzou being less than 60 miles (92 km) from Algiers, compared to Batna, the capital of the Aurès region (about 400 km), Ghardaïa, the capital of the Mzab (about 600 km) and Tamanrasset, the capital of the Ahaggar Tuareg (2,060 km). In addition, there is a large Kabyle element – at least 25 per cent and possibly approaching 40 per cent – in the population of Algiers itself.

Third, like the Mzabis but unlike any other Berber group in Algeria, the Kabyles have a highly developed commercial tradition and there is a large Kabyle diaspora; this is both much larger and more diversified than its Mzabi counterpart.

Fourth, unlike the Mzabis or the Tuareg, the Kabyles have been accustomed, for several generations, to engage in labour migration to France (and to a lesser extent to Belgium, Germany and Switzerland). In this the Chaouia have resembled them to some extent, but in quantitative terms Kabyle labour migration has far surpassed that of the Chaouia: the wilayāt8 which provided the most emigrés in 1966 were Setif (which then included the western and central districts of Lesser Kabylia – the present wilāya of Bejaïa – and was 40.5 per cent Berberophone) and Tizi Ouzou (i.e. Greater Kabylia, 81.8 per cent Berberophone); these accounted for 24.8 per cent and 20.5 per cent of Algerians resident abroad respectively, compared with the wilāya of Batna (44.5 per cent Berberophone), which accounted for a mere 5.6 per cent.9 And in recent decades Kabyle communities have established themselves in North America as well.

Fifth, Kabylia received preferential treatment in educational provision during the colonial period. As Fanny Colonna has pointed out, however, the Mzab and the Aurès were also, initially, offered above average educational opportunities by the French, but proved less receptive to these than the Kabyles. In the case of the Chaouia, the often dispersed habitat and the prevalence of transhumance may account for their relative failure to take advantage of French schooling. In the case of the sedentary, urban-dwelling, Mzabis, it was a matter of explicit resistance. The seven cities of the Mzabis,10 as a consequence of their religious particularism, had long possessed their own developed educational system, which survived into the post-colonial era, and their populations shunned the educational services of the infidel French. The Kabyles were also entirely sedentary, like the Mzabis, but lacked both any particular religious fervour and all but rudimentary educational institutions of their own.11 There were no major obstacles to Kabyle acceptance of the opportunity of cultural development, with its implications of upward social mobility, offered by the French once this had ceased to be associated with the enterprise of religious conversion. By no means all Kabyles underwent this particular process of cultural change directly and it was not until after the Second World War that French schooling was generalised throughout the region. But a large number of Kabyles did respond eagerly in the early period, with the result that, for example, of those Algerians of rural12 origin studying at the École Normale at Bouzaréah near Algiers between 1883 and 1939, 89 per cent were from Kabylia, and 77 per cent were from Greater Kabylia alone.13

There thus developed a substantial Kabyle intelligentsia, Francophone and modernist and linked to both the migrant workers in France and the villages of the Jurjura and the Soummam valley whence these came. This combination of the experience of French education and that of mass labour migration to France was undoubtedly an important factor underlying the sixth major difference between the Kabyles and the other Berber populations, the immensely greater role which the Kabyles played in the nationalist movement and the leadership of the wartime National Liberation Front (Front de Libération Nationale, FLN) and the National Liberation Army (Armée de Libération Nationale, ALN).

Kabylia not only constituted one of the six military regions (wilayāt) of the ALN, wilāya III, it also provided most of the commanders of wilāya IV (the Algérois), the first commander of wilāya VI (southern Algeria) and the successive commanders of the important Fédération de France du FLN (FFFLN). In addition, it was a Kabyle, Abane Ramdane, who emerged as the overall political leader of the FLN in 1955–6 at the same time as the architect of wilāya III, Belkacem Krim, emerged as the most influential of the ALN commanders. It wa...