This is a test

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In a mist-shrouded valley on China's invisible border with Tibet is a place known as the 'Kingdom of Women', where a small tribe called the Mosuo lives in a cluster of villages that have changed little in centuries. This is one of the last matrilineal societies on earth, where power lies in the hands of women. All decisions and rights related to money, property, land and the children born to them rest with the Mosuo women, who live completely independently of husbands, fathers and brothers, with the grandmother as the head of each family. A unique practice is also enshrined in Mosuo tradition - that of 'walking marriage', where women choose their own lovers from men within the tribe but are beholden to none.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Kingdom of Women by Choo WaiHong in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Arriving in the Kingdom of Women

Once in a blue moon, a traveller may be lucky enough to come across the mention of a place so intriguing, so mysterious, that not to answer its call would be unforgivable. It was months since I had quit my job. Following my urge to discover what China would hold for me, I had spent my time travelling to the more widely known cities and countryside of this vast country of my ancestors. Then I came across an article in a travel magazine about a remote tribe in a corner of Yunnan where the people worshipped a mountain goddess called Gemu.

This tribe, located by a lake in the far eastern foothills of the great Himalayan range, apparently was one of the few surviving matrilineal societies in the world. It struck me as incredible that a matrilineal society still existed in the twenty-first century, let alone in the depths of patriarchal China. This is the land where patriarchy is so deep-rooted that a male-biased mentality has, mainly through abortion, produced a skewed gender imbalance of nearly 120 boys born to every 100 girls today. This is also the place from which my grandfather fled to escape poverty and start a new life in Malaysia. There he planted his traditional patriarchal roots, which produced in my father an intransigent preference for boys and which in turn produced in me a stubborn advocacy for fair and equal treatment of women in a man’s world.

To say that the feminist heart in me was beating a little faster on reading that this Mosuo tribe practises a religious ceremony celebrating a female deity would be an understatement. Even the name given to this tribe by the Chinese, the Kingdom of Women, conjures up an unimaginable world populated by present-day Amazons.

I was curious to find out just how the story of the Mosuo tribe came about. Equipped with only a limited mastery of the Chinese language, I trawled through books and articles written by anthropologists, historians, journalists and sociologists, and pieced together an introduction to the story of the Kingdom of Women.

A couple of thousand years ago, or even longer depending on which book you read, the Mosuos, originally known as the Na people, walked from the high mountains in the north-west to where they are today, in search of a kinder climate. They must have trekked for years and years, passing over countless harsh mountain ranges before coming across a great plateau situated in a lower altitude, much more hospitable than their previous homeland.

There they eyed a beautiful lake under the shade of a high granite mountain. By its shore, they found the weather warmer, the spring water clearer, the soil richer and the pine forests with wild animals and plant life more abundant. Their discovery led them to settle down among the knolls and valleys studded around the Yongning plateau by the lake. They claimed the lake as their own and graced its life-giving waters with a name recalling the greatest female force, that of the Mother Lake, or Xienami. The lake was renamed later as Lugu Lake because it is shaped like a ‘lugu’, a water container made from the dried shell of a gourd. More significantly, they claimed the mountain as their own, acknowledging it also as female, in the form of a new beautiful goddess and protectrix, Gemu.

The Na people brought with them their old way of life, gathering forest produce, hunting animals big and small and planting rudimentary crops on their small homesteads. They also brought along with them something precious from the past, a past so remote that some historians say it was as old as the dawn of human history. This precious relic harks back to a time when the world was full of deities representing the many faces of nature, the main ones almost always wearing a female face. Modern scholars may label them merely as fertility goddesses but they formed the spiritual bedrock of human society then.

This spirit of embracing the female as the building block of society, represented by Gemu Mountain Goddess, was the jewel in the crown brought by the Na to the Mother Lake. As they began building up their new lives, they re-organized their community along the well-worn path adopted by their foremothers, that of creating and linking family members by their matrilineal bloodline. They built large homes with pine logs cut from the mountainside to house their female-descended families, taking pains to stay connected to the primal maternal thread.

The puzzle of how the Mosuos came to be what they are may never be solved definitively, but if I may borrow from the school of thought that suggests that all humankind started out as matrilineal societies, I would venture to say that the history of the Mosuos must have dated back to the beginning of the human epoch tens of thousands of years ago.

That the Mosuos have been strictly matrilineal over time is not in doubt. That they worship the forces of nature just as our forebears did in early pagan societies is also evident. That they revere most of all Gemu, a female mountain goddess, among the many deities they hold dear, harkens back to the oldest human tradition of worshipping the Great Goddess and other lesser goddesses in the Old Stone Age of human existence.

Archeologists have uncovered many instances of ancient goddess worship throughout the world. There was the original Great Goddess, the Mother Goddess, there was the Goddess Hera in Greece, the female deity Isis in Egypt, Parvati the Goddess in southern India, even Berehinia, the Mother Goddess of Russia. China had her own Great Goddess, Nu-Wa. Following these female-centric traditions, perhaps the Mosuos can claim an unbroken direct link to those early days of human society. And just maybe they can further claim to be one of the few remnants of the original matrilineal human society.

The real puzzle is how the Mosuo tribe has managed to cling tenaciously to that ancient matrilineal tradition without succumbing to later paternalistic influences all around them.

Compare the Mosuos on the western side of Lugu Lake who to this day remain staunchly matrilineal, to their cousins on the eastern side of the lake who have become patrilineal over time. The eastern Mosuos chose to adopt the paternalistic alternative, having paired up with Mongolian troops who remained behind after Kublai Khan annexed Yunnan to China in the thirteenth century. The Mongols brought with them their male-centred way of life to the eastern Mosuo community, who so identified themselves with being the descendants of Mongols that in recent times they had successfully petitioned to classify themselves as belonging to the ‘Mongol’ minority tribe, not the Mosuo tribe. But despite the patriarchal conversion of their eastern cousins, the western Mosuos remain untouched by male-centric influences.

It was not just against the influence of their immediate Mosuo cousins that the tribe held fast to its matrilineal heritage. Against all odds, the tribe kept its matrilineage despite coming into contact with other neighbouring mountain tribes that venerated male gods and followed a patriarchal tradition.

More tellingly, the Mosuos have so far been able to withstand the pressures brought about by the male-dominated Chinese culture that took root 5,000 years ago and spread throughout China. Han Chinese patriarchy is intense and all pervasive, continuing to hold sway even in contemporary China. Born and bred in the same cultural milieu adopted by a largely Chinese immigrant society in Singapore, I too am familiar with navigating a world where men are the bosses both at home and outside, and where women find themselves relegated to a place in the family way behind their husbands and sons. Things may have improved for women since they entered the workforce at all levels in this century, but, for all that, patriarchy remains omnipresent in Chinese society.

To me the story of a people who pay homage to a goddess in a world full of father figures as godheads and follow a matriarchal way of life in a world where patriarchy rules is so interesting and entirely unique that it seems too good to be true. I felt the need to get up close to a real goddess waiting to be seen and touched. I wanted to see for myself just how this tribe manages to exist as a feminist oddity in patriarchal China.

Dropping all my other travel plans, I made straight for Lugu Lake, set in the remote south-westernmost province of Yunnan in China. As luck would have it, I timed my visit to coincide with the Mountain Goddess Festival held every summer in honour of Gemu. The festival is known locally as Zhuanshanjie, or ‘Perambulating Round the Mountain’ in Chinese, and is the most important festival of the Mosuo people.

Gemu the mountain deity is a giant granite mountain sitting 3,600 metres astride Lugu Lake situated deep inside high mountains. Had I travelled there 90 years ago, as did the Austrian botanist-explorer and writer Joseph Rock, it would have taken me seven days to ride horseback from the nearest old tea-trade centre of Lijiang over an ancient mountain trail across nearly 200 kilometres of rough terrain. As it turned out, I set off from Lijiang in the comfort of a chauffeur-driven car speeding on a modern, winding tarmac road.

The drive was scenic although arduous as we wound our way up and down the mountainous route. This was pine-studded countryside with spectacular vistas of snowy mountain peaks and small valleys washed by the Jinshajiang, the Golden Sand River, the first tributary of China’s great Yangtze River. The going was not easy, as the narrow two-way single-lane road was perched precariously over steep mountainsides with frequent traffic jams caused not so much by cars as herds of mountain goats and cows ignoring the traffic in search of green pastures on the other side.

At the end of a gruelling seven-hour journey, the car ascended a final crest and, turning round a curve of the road, revealed a picturepostcard view of a majestic blue lake. That first sight of Lugu Lake, no matter how many return trips I make, never fails to take my breath away. Nestled within ring upon concentric ring of mountain ranges, the large lake has a beautiful serpentine shoreline punctuated with hundreds of tiny isthmuses, studded with endless rows of Christmas pine trees dipping right by the clear water’s edge.

On the day of my arrival under a clear blue, cloudless sky, the lake reflected an intense azure blue, the bluest blue I had ever seen. On a nasty day, with rain-soaked clouds hanging overhead, Lugu Lake turns a moody slate-blue hue. On a crisp cold winter’s day with the sun shining brightly, the lake transforms itself into a bright emerald green body of water.

As I gazed from the lake to the horizon, a tall stone sierra sat majestically across the entire length of the shoreline on the far side. Oddly, the montane structure bore a distinct shape. Squinting my eyes, I focused on the massif taking on the shape of a human-like figure, the outline of which looked just like a reclining woman in profile, a forehead rising to an aquiline nose ending in an elegant chin, framed with a gentle cascade of long hair flowing down the summit head. The profile traced the chin down to a beautiful neck that rose towards an upturned generous bosom before sliding into a slight hint of a tummy, with the rest of the reclining body trailing down like a long graceful skirt. The entire picture bore an uncanny resemblance to a female form in repose.

‘There she is, Gemu Mountain Goddess!’ my driver chipped in to give voice to my unspoken thoughts.

So I had finally come face to face with the lady mountain deity. This unique female demiurge would be the object of special worship by the Mosuo tribe at the Gemu Mountain Goddess Festival the following day.

On the day of the festival, I rose early to a wet morning, the summer rains having arrived with a vengeance overnight. I waded through puddles to my driver in the waiting car. Making our way to the site of the festival, we swished over a muddy wet track hacked from the side of the mountain meant more for horses than cars. We bumped over squelchy potholes as we drove on until we ran right into a mighty big one. Revving hard, the driver got stuck deeper and deeper, spraying wet mud all over the place. Mercifully a couple of passers-by kindly came forward to help out, and somehow with the help of a few boulders and planks thrown in the path of the wheels, they managed to push us out of the pothole and send us on our way.

Before long, I saw in front of me crowds of people scurrying up a hillside, with more arriving by horseback and motorbikes. We had arrived just in time to witness the start of the festivities.

Unfolding before me was a lively scene. Locals dressed in their ethnic finest were busy pitching makeshift tents, tending to open fires, watching over pots of steaming rice and boiling broths, flitting about chatting with old friends and relatives. Children screeched with delight as they played catch with each other. In pole position sat a huge tent housing a group of Tibetan Buddhist lamas, the keepers of the faith, with two of their number blowing long alpine horns to herald the start of the festival.

A stream of worshippers trekked slowly up the slope towards a small simple white shrine built on a rise up on the northern face of Gemu Mountain. I trailed them to the worship site and watched the throng of women and men going through their paces as they paid homage to their mountain goddess.

‘How do you do this?’ I asked a friendly face.

‘You first light incense and pine branches,’ she said, handing some to me, ‘and put them in front of the shrine. This is to get Gemu’s attention.’

I followed her instructions. Then she beckoned me to follow her up the few steps to stand before the shrine.

‘Just do what I do,’ she said.

She put her palms together in the universal prayer mode, then positioned them first to her forehead, then her mouth and finally next to her heart before getting on her knees. In a half-prostrate pose, she opened her palms and placed each on the floor on either side of her and lowered her head to place it on the ground. She got up again and repeated the ritual two more times. After the third prostration, she got up and with palms pressed together in front of her face mouthed a silent prayer with her eyes closed.

She waited for me as I went through the paces, and indicated to me that I should follow her as she began her pilgrim’s circumambulation round the shrine three times. This was done in a clockwise direction as she continued to mumble her prayers quietly.

Lastly, she unstrung a length of Tibetan-style prayer streamers and tied both ends up on tree branches by the side of the shrine in order for the wind to hurry her prayers to the goddess.

‘I prayed for Gemu to be happy and also to bless my family with another year of plentiful harvest and good health,’ she explained later when I asked her to tell me about her prayers.

After thanking her, I followed the crowd down the slope to mill around the merry-makers. People gathered around a patch of green to wait for the start of the entertainment. A Mosuo man strode centre stage and lifted his flute to his lips. Softly he blew a soulful tune which I was later to learn was the usual signal for the start of the circle dance. A few brave souls stepped forward eagerly to link their hands and began moving to the rhythm of the flautist’s music and gait as he led them round the makeshift dance floor.

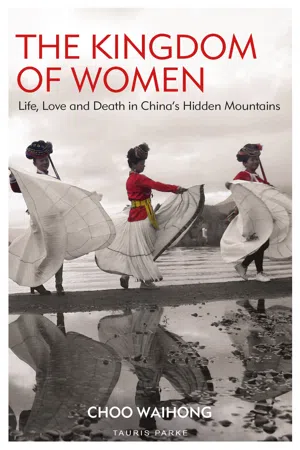

Soon more locals joined in, hurrying to assume their positions in the dance line, the men in front, the women following and the children trailing behind. And dressed up they all were, the women resplendent in their colourful headdresses matching their multi-hued tops, swishing their long flowing white skirts, with the men jaunty under cowboy hats in their bright yellow tops. Everyone joined hands to form a dancing circle behind the piper as he continued with his four-beat tune. Keeping beat, the men stomped in their high boots, the women danced gracefully and the children struggled to keep up. Now and then the dancing troupe broke out in loud chorus, singing to the familiar tune.

As the dancing continued, the onlookers made their way to their tents for an afternoon of feasting and wining. I too went in search of lunch and struck lu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Plates

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- Prelude

- 1. Arriving in the Kingdom of Women

- 2. Building a Mosuo Home

- 3. Going Native

- 4. Getting to Know the Mosuos

- 5. Becoming the Godmother

- 6. Hunting and Eating in Bygone Times

- 7. How the Mosuo Women Rock

- 8. The Men Rock Too

- 9. A Marriage That Is Not a Marriage

- 10. The Matrilineal Ties That Bind

- 11. The Birth-Death Room

- 12. On the Knife-Edge of Extinction

- Glossary