![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Although the world is contracting and becoming smaller as we acquire insight into an ever-increasing number of cultures, there are still many peoples with their own cultures, lifestyles and social organizations that are totally unknown to many of us. We do not know how social life in other societies manifests itself under completely different circumstances than the ones we are accustomed to. We still know little about other peoples’ living conditions, beliefs and traditions. We know little about what and how they think, what their perception of reality is, how they organize their lives, how they perceive themselves and others, how they view their and others’ actions, how they view the world, what their social manners are, how the family is organized, how kinship relations function, how they justify their actions, what in life is important for them and so forth.

The interest in cultural differences has been increasing, and this has its own background; during the last 35 years, Western Europe has become a meeting place for people from practically all over the world. These people come from very different cultures and societies. They bring different perceptions of reality with them, and they have different premises. While we do not have sufficient knowledge about all the cultures and the societies that these different people come from, we are acquainted with different cultures to varying degrees. Some of these cultures and societies have already become familiar in Europe. Some are less familiar and some are totally unknown.

A considerable growth in immigration in the second half of the previous century has created a wholly new situation in the wealthiest parts of Europe. This has not only created problems but also an increased interest in new knowledge about other societies, cultures and ways of life. To communicate with people from different cultures, one must have a certain familiarity with their culture and society. Such familiarity contributes to enriching the communication between people. Because in multicultural societies, as Europe has gradually become and would like to present itself, there is a growing demand for cultural expertise. Familiarity with other cultures is an important premise for communicating with people from a different background. Therefore, it is important for each of us to learn a little about other societies, cultures and ways of life, which can help us to better understand from different backgrounds than ours people.

Because of differences in culture, we experience communication problems, misunderstandings and conflicts. It is necessary to learn about each other’s backgrounds to avoid such problems, to better understand each other. First, one has to learn about how others live and what their perceptions of reality are, in order to compare them with one’s own culture. To learn these things, we must either participate in or really familiarize ourselves with other people’s realities, their thinking patterns and lifestyles, on, quite simply, we must try to live as they do. One must nearly remould oneself in another culture both to understand it and to participate in it to the greatest possible extent, even if one does not identify oneself with it. From experience, I know that it is fully possible for one with a foreign background to communicate with people from a different culture, share thoughts and to experiment without insurmountable problems. Understanding people from a culture does not require becoming similar to them. Yet it presupposes that we have fairly strong reservations against our acquired notions and beliefs about what is right and wrong, and what is worth relating to and what is unworthy. What is right for a Norwegian need not be right for a Kurd. Such an attitude is key to entering other peoples’ worlds.

Fredrik Barth (1991) has taught us that human beings who are not particularly informed about other cultures value their own culture and way of life highest, without giving any further thought to the subject, and often think that they are the only right ones. Such an understanding of culture has unfortunate aspects. First, this type of opinion acts as a barrier that prevents human beings from learning about other cultures and lifestyles. Second, it will hinder development of increased understanding between cultures. An example we often experience is the following: when we are communicating with people from cultures that we either have not known previously or are less acquainted with, we discover quite quickly that we have been rather ignorant of their culture or way of life. Gradually we discover that their priorities are different than ours, they perceive themselves and the world differently to we do, and they do things differently. Briefly, one will see that there are other mechanisms that govern their lives. The Zaza people, the Kurdish-speaking group in Eastern Turkey on whom this book focuses, are a very relevant example for illustrating the problems presented above. The Zaza largely have their own ancient arrangements that keep the social order by restricting and solving conflicts between people. Their social organization consists of spiritual- and kinship-based authorities similar to feudal systems. The authorities set the norms for their subjects and are sources of both pleasure and grief for them. In this book, I will present information about Zaza social organization, which regulates their social life. The main question is what social arrangements contribute to the endurance of a society that does not have any connections to the state.

Very little is known about the Zaza Kurds and their society. Acquaintance with this people’s ways of life, beliefs and traditions provides us with new knowledge about other human beings, cultures and societies. Much of the life philosophy that the Zaza practise conflicts with quite a few fundamental Western ideas but, all the same, we must understand why it is meaningful for those who practise it. First we must know how they live, why their way of living is so different from ours, why they live thus, etc. In this way, we can expand our understanding of other ways of living. Whether we are natives or immigrants, this expansion of our comprehension also raises questions about who exactly ‘we’ are. The material in this study is meant to provide knowledge for further reflection on and expansion of multicultural understanding. But, first, a short presentation of the Zaza people is in order.

The Zaza region and its population

The Zaza-speaking Kurds are a people who can bring us closer to ancient Middle Eastern civilizations. The Zaza region is an area on which Persians, Armenians, Arabs, Mongols and Turks have left their marks. But these groups have been perceived as intruders and oppressors. Throughout history, the local population has successfully fought against intruders to preserve its distinctive character. They are also very uninfluenced by modernity and are associated with an agricultural lifestyle.

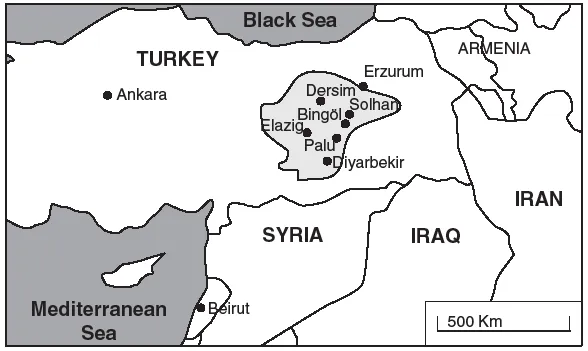

In this book I mainly analyse the Solhan District and attempt to link this community to the surrounding communities (see Figure 1.1). Solhan itself is a small Zaza town and the seat of district administration. By European standards, Solhan is perceived as a small town, with a Turkish administrative unit consisting of a large garrison, governmental quarters housing the offices for the public prosecutor and the magistrate, and other local authorities and the police. The administration in Solhan is, in its turn, subordinated to the governor’s office in the province capital Bingöl. The province governor is appointed by the Ministry of the Interior in Ankara and has the formal power, but the real power is in the hands of the military.

About 20,000 people live in Solhan itself and between 70,000 and 80,000 live in about 70 surrounding villages. Administratively, the villages are connected with Solhan. Virtually everyone in the Solhan region belongs to the Zaza population. They are of Kurdish descent and speak a Kurdish dialect, which is referred to by others as either ‘Zaza’ and ‘Dimili’, but their own name for the language is ‘Kirdki’, which means Kurdish. Zaza or Kirdki is widespread as a spoken language among Zaza-speaking Kurds. This dialect is one of the three largest Kurdish dialects and is spoken by approximately 3 million people. The two other dialects are Kurmanji, which has the greatest number of speakers, and Sorani, with the second largest number of speakers. Yet there is a certain disagreement among linguists about whether Zaza is a dialect of Kurdish or not. Most specialists of Kurdish, among others Lerch (1857, 1858), claim that Zaza is a dialect of Kurdish, while a few (e.g. MacKenzie 1962; Paul 1998) assert that Zaza is perhaps a separate language and that the Zaza originally came from North Iran. But newer genetic research (e.g. Nasidze et al. 2005) shows that the Zaza are genetically very close to the other Kurdish groups such as those speaking Kurmanji in Turkey and Sorani in Iraq. These investigations also show that the genetic distance between the Zaza and other North Iranian peoples is large.

I investigated closely the disagreement about whether Zaza is a Kurdish dialect or a separate language, especially among the elder section of the population. All rejected categorically the claim that Zaza is a separate language. They were completely convinced that Zaza is a Kurdish dialect. None had ever felt that they were not Kurds. Neither had they previously heard that they were not Kurds. So, it was an unfamiliar proposition for them. Some of them directly said that such statements are Turkish inventions, and indicated what Turkey might want to achieve by such propaganda:

We are abused by the false Turkish propaganda. For 80 years we have heard that Kurds did not exist, that we were mountain Kurds–well, it was something they invented themselves. We were expected to buy it, but we did not. Because of EU membership, we now hear that the Kurds exist after all.

Zaza-speaking Kurds mainly live in Bingöl and its surrounding areas, Solhan, Darĕ Yĕni, Palu, Piran, Dersim and the adjacent areas. The aforementioned areas are considered to be the core areas for the Zaza. Areas such as Aldus (Gerger in Turkish), Kahta, Koluk (Gölbasi) and Besni in the Adiyaman province are also considered to be Zaza areas. Many Zaza also live in parts of Siverek, parts of Xarput (Elazig in Turkish) and parts of the areas north of Diyarbekir. Otherwise Zaza Kurds are thinly distributed throughout the neighbouring provinces of Mush, Erzincan, Malatya and Ruha (Urfa in Turkish, see Figure 1.1). There are no official statistics on the Zaza people, because Kurds are a taboo. It is estimated that around 3 million Zaza-speaking Kurds live in the area.

The Solhan region lies between Bingöl in the south-west and Mush province in the east. The districts of Solhan consist of pastures, lush river valleys surrounded by high mountains partly covered by vegetation with bare summits in the east, west and south. To the north lies the Mesopotamian highland, with rich water sources that separate valleys and often establish the boundaries between villages. These manifold rivers flow into the Murad River which runs through the districts of Solhan and constitutes one of the largest branches of the Euphrates, on which Turkey has built several gigantic dams and power plants. The area consisting of the town of Solhan and the villages around is called Meneshkut and lies close to the Sherevdin Plateau in the north. The villages that lie to the south and west of the Murad valley are called Wever and Solaxan. In the summer, the vast, beautiful highlands are used both by the villages in Meneshkut and the nomadic Kurdish-speaking Beritan tribes. Beritan tribes have an ecological adaptation and migration pattern that somehow differs from those of the sedentary Zaza pastoralists. The Beritan nomads mainly winter on the plains at the Syrian border and move to the grazing lands on the Sherevdin Plateau in the summer.1 Grazing lands in Sherevdin (see Figure 1.2) are controlled by the sedentary Zaza, and the Beritan nomads’ access to the grazing lands is wholly dependent on the respective relations between them and the sedentary people.

Figure 1.1 Areas where Zaza-speaking Kurds live

Source: Adapted from the original by Martin van Bruinessen (1992).

Figure 1.2 The Sherevdin landscape, with a flock of sheep in the middle

Photo: Mehmed S. Kaya.

The low plains have been settled by humans for a long time but nobody knows precisely how long because archaeological excavations have not been allowed. Mountain dwellers live in valleys up to 2,000 metres above sea level. Many of the valleys to the south of Murad River are remote and nearly inaccessible. Here there are quite a few villages that still have little contact with the outside world. The main road from Xarput (Elazig), which serves the trade with Iran, passes through the Solhan region. But people recount that until recently they dared not live near the main road for fear of being seen by the dreaded Turkish gendarmerie. Therefore, they hid their settlements away from it, deep in the valleys and ravines or behind mountains, so that they would not be discovered by the military. Fear compelled them to protect themselves physically from the outside world. However, during the last ten to 15 years, more people have begun living around the main road.

The Zaza are mainly a tribal society. Its people, especially in the mountain villages, are affiliated with tribes and tribal relations are strongly maintained. The right to use the village communal land and outlying fields is collective but usually controlled by prominent village leaders, who are often members of a tribe. It is a society with great social differences: a few rich landowners with power and prestige, and a large majority of small farmers and landless tenants. Most small farmers own from five to eight acres of fertile land. Perhaps up to 40 per cent of the population has become landless in the last 30 years due to the high population increase. The landless live either as tenant farmers or as seasonal workers in the large cities of Southern and Western Turkey. Animal husbandry is their most important livelihood. Each family owns around 50 sheep on average and each nuclear family has six to eight children.

The living standards for most people, including those in the Solhan District, are very low. They can only be compared to the living conditions in Afghanistan and in large areas of Africa. Most people are poor, undernourished or malnourished. The houses they live in are more or less on the same level as the ones Medieval Europeans lived in, that is, they had dirt floors, no indoor plumbing, rustic conditions, and the like, although architecturally they are totally different. The houses lack running water and many do not have toilets. Most people use outhouses or nature itself for this purpose. Women come together to do laundry by the rivers a stone’s throw from the villages. People live very close to the animals in their daily lives, nearly side by side. Donkeys, cows and lambs soil around the houses, day and night, year-round.

People here have shorter life spans than does the rest of the population in Turkey. Life expectancy is scarcely more than 50 years. Mortality rates are particularly high among children and women, striking especially the poor. This is due to several reasons but the most important cause is that most people do not have any access to proper health care because the health services are non-existent in the villages. The nearest health service is in Solhan but they seldom receive adequate treatment there, either because they cannot afford it or the health service lacks the necessary expertise. To get better health care, they must travel to the larger cities that are far away, and many cannot afford to do so. In addition, the religious belief that ‘one’s fate is predestined by Allah’ substantially contributes to the high mortality rate. Many are even unaware that their wife or children can be saved by medical science, so they believe that life is determined by fate and its course cannot be changed by man. No developmental work has been done to educate people on how things can be improved.

More than half the population have either never had schooling or are functionally illiterate. About one third of the population has had primary schooling for five years, and less than 1 per cent is educated past this. According to the modern definitions of literacy, the Solhan region can be described as an illiterate society. The low level of education has contributed to the fact that here social arrangements are based on their own experiences, which are totally different from the modern governmental arrangements.

At the same time, I must point out that Zaza society should not be considered to be a simple one. As with all other societies, Zaza Kurds have built up a relatively complicated society. The reader must therefore not derive too simple an interpretation of the description of the society, but try to understand each statement in a larger context of social complexity. Although large sections of the society still live by old values, the totality of the Zaza society consists of many collective units and actors, and diverse relations, including the ones between genders, social processes, ideological currents and creeds. These conditions contribute to producing principles about social formations, hierarchical systems (social hierarchies), forms of government, forms of communication and production, and social arrangements to order these social relations. A religion such as Islam is not a single entity that can be understood in a simple way, but encompasses a series of religious expressions and relations that must be understood according to the Zaza people’s difficult situation in Turkey.

Likewise, kinship is not to be understood as a simple phenomenon of the patriarchal or matriarchal type. Instead, these concepts must be interpreted contextually as expressions for the dominant social relations. These relations may vary according to groups, individuals and single incidents.

Nor are the relations between men and women are not unambiguous and simple to understand, although they can appear to be traditional. Gender relations are marked by religious and traditional notions, as they are at the same time connected with practical tasks, and are subject of exchange, cooperation and discussions to different sorts. The view on gender is connected with ethical and philosophical reflections about human behaviour, but at the same time it may be tied to the debate on the meeting between the Kurdish society and modern and global development. Therefore, this book’s intention is to show how members of the Zaza Kurdish society try to solve their tasks and meet challenges in the context of grave problems experienced...