![]()

Part I

Material Sabotage: Ensnaring, Burning, Trespassing

![]()

1

Entrap, Engulf, Overwhelm

From Existentialism to Counterculture in the Work of Marta Minujín

Catherine Spencer

In the words of her friend, the critic and curator Jorge Romero Brest, the Argentine artist Marta Minujín launched herself into a transnational network of avant-garde activity with ‘a true auto-da-fé’ (2000, 4), committed in Paris during June 1963. La destrucción [The Destruction], which has subsequently become one of her best-known happenings, saw Minujín gather together a series of assemblages made from old mattresses, cardboard, and sutured textile sections, all of which she had fabricated while living in the city during the preceding year, and drag them into an empty lot on the Impasse Ronsin.1 Minujín then invited a group of artists she had met in the French capital to alter her constructions with their own stylistic flourishes – to, as she put it, ‘delete, erase, modify my works’ (2004, 61) – before setting fire to the sculptural conglomerates in a spectacular pyre of metaphorical and tangible self-immolation.

If La destrucción signals the centrality of sabotage to Minujín’s practice during the 1960s and 1970s, then the work also reveals its complex operation. At its most overt level, sabotage functions in Minujín’s oeuvre as an act of wilful destruction, through which artworks, participants, audiences and the artist herself all come under attack at various points. While this attack is often explicitly physical, it is also implicitly psychological. More specifically, by constantly endangering her work through erasure and ephemerality, and as a result questioning artistic authority and agency, Minujín employs a form of self-sabotage that often verges on nihilism, as the processes she sets in train seem actively to engineer her work’s un-doing.2

Minujín’s sculptures, installations and performances frequently test the seductive appeal that obliteration might have for the individual subject, through immersion as much as destruction. Yet Minujín’s work also continues to embrace the paradoxically enabling qualities of sabotage – in La destrucción, for example, the display of self-sabotage also provided a passport into established communities of artistic exchange, such as the French Nouveaux Réalistes. Brest’s intriguing characterization of La destrucción as an ‘auto-da-fe’, in which Minujín simultaneously appears as instigator and victim while the mattress-assemblages accrue heretical implications, alerts us to the subversive connotations of her artistic approach. While sabotage in Minujín’s work might appear connected with self-destruction, there is often a clandestine agenda at play that seeks to redefine subjectivity, rather than accepting its dissolution.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Minujín travelled between the different cultural and political contexts of Argentina, France and North America, creating installations, environments and performances in Buenos Aires, Paris, New York, Montreal and Washington DC. The diverse body of work Minujín created in this period encompasses her Colchones (sculptures using mattresses) (see Figures 1 & 2), participation in collective exhibitions such as La feria de las ferias [The Fair of the Fairs] (1964), happenings like Suceso plástico [Plastic Event] (1965), and environmental installations including Importación-exportación [Import-Export] (1968) and Espi-art [Spy-Art] (1977). This chapter argues that, through these works, Minujín explored the roles played by aggression and self-obliteration in social interaction. Initially, this exploration was informed by an existentialist worldview, but as the 1960s progressed it became linked to an increasing alignment with the carnivalesque irreverence of international counterculture. While existentialism and counterculture might initially seem poles apart, this chapter proposes that the nihilism of the former prepared the ground for Minujín’s affinity with the collective disaffection evidenced in the latter. Her responses to both influences were underpinned by a consistent attentiveness to the experiences of alienation and the loss of a clear concept of self, and to the processes by which a subject might be reduced to an object.

Many of Minujín’s performances and environments have been concerned with either intervening in established cultural groupings, both within the art world and in wider communities, or delineating alternative ones. Even her particular take on the happening as a form, and the extremity with which she imbued it, can be seen as a manifestation of this approach. While La destrucción was Minujín’s self-proclaimed ‘first happening’ (2000, 61), critics such as Alicia Paez noted that the concept of the ‘happening’ was an awkward imposition on the Argentine avant-garde by critics and artists from the US, ‘where the true history of this genre has developed and where the word which defines it emerged’ (1967, 21).3 Within this context, sabotage emerges as both an effect of everyday interaction, and a tool that can be deployed to negotiate the cultural field, and carve out unconventional artistic and social spaces. While Minujín’s shifting forms of sabotage have never been explicitly political, they are not without a politics, intimately linked as they are with the simultaneously terrifying and elating instability of the subject’s being in the world, and with a consistently anti-conservative investment in the fraught possibilities of individual freedom.

By situating sabotage and self-destruction, particularly the strategies of ensnaring subjects and bombarding them with sensory phenomena, as integral to Minujín’s artistic productions of the 1960s and early 1970s, we can begin to account critically for her work’s deliberately provocative aspects, and regain a sense of its potential to challenge normative social constructs. The Argentine and international press feted Minujín in this period, while her embrace of celebrity and an unashamedly populist approach has fostered the view that her work is a fashionable confection.4 Even Minujín’s defenders have been cautious in their appraisals: for example, in his 1967 book El ‘pop art’ Oscar Masotta observed that Minujín’s artistic approach manifested ‘a strange mix of absolute rejection and a total acceptance of the effective structures of real society’ (1967a, 28). More recent commentators such as Christian Ferrer, while celebrating the experimental nature of Minujín’s enthusiasm for technology, have highlighted the danger that ‘with hindsight, what seemed like a rupture, novelty or even scandal now reveals itself as something short-lived, a bit fruitless, or not as radical as it promised to be’ (2010, 72). By contrast, this chapter argues that Minujín strategically deployed apparent self-sabotage as a means of infiltration, subversion and even entrapment, while establishing a place for herself within international avant-garde networks and creating a role for the woman artist as director and orchestrator, rather than model or muse.

‘Laying Traps and Dangling Baits’

Minujín has cast her movement into non-traditional media during the early 1960s, specifically the use of mattresses as a material that she would paint in vibrant colours, as an act of determined self-sabotage. ‘When I was 18 or 19’, the artist recalls, ‘I was a very good painter, so good that I was bored with it. So one day I punched a hole in the middle of my painting, took the mattress off my bed and said “I’m going to work with mattresses” [… and] made a kind of plastic house’ (2000, 230). While many Argentine artists, notably those associated with Kenneth Kemble’s Arte Destructivo initiative, started to use non-traditional materials in their work during the 1950s and early 1960s (see Giunta 2007, 119–162), Minujín seems to have chosen mattresses specifically for their overblown, even histrionic associations with erotic and terminal dramas.5 By using mattresses, Minujín wanted ‘to symbolise how people spend half their life in bed: they are born, they love, they die’ (cited in Romero Brest 2000, 1). As if literalizing these connections, during the 1962 exhibition El hombre antes del hombre [Man Before Man] at the Galería Florida in Buenos Aires Minujín arranged for a photographer to capture her perched gingerly inside one of the resulting Colchones [Mattresses], gazing out from its frame-like armature (see Figure 1). The formal rupture enacted by Minujín’s use of assembled found objects, which here includes sections of cardboard boxes as well as mattress material, becomes transposed into an evocation of psychic threat and entrapment. The pliant, yielding material of the mattress supports her body but also contains it: there is a sense that the construction might snap shut at any moment, devouring its occupant.

Between 1961 and 1963, as she moved back and forth between Buenos Aires and Paris for two extended stays in the French capital, Minujín actively pursued the threat of potential equivalence between embodied subject and object posed by the three-dimensional mattress constructions. While in Paris, Minujín began to construct what she describes as ‘invented mattresses’ (2004, 61), recounting how: ‘I bought fabric and a glue pen and managed to borrow a sewing machine and the first one I made was my first environment […] a kind of mattress-house […] that construction I hung in the centre of the studio and people could enter and leave it as they wished’ (61). Minujín’s architectural conceptualization of these three-dimensional sculpture-installations is borne out by their immersive, enveloping qualities, revealed in surviving photographs of destroyed or lost works.

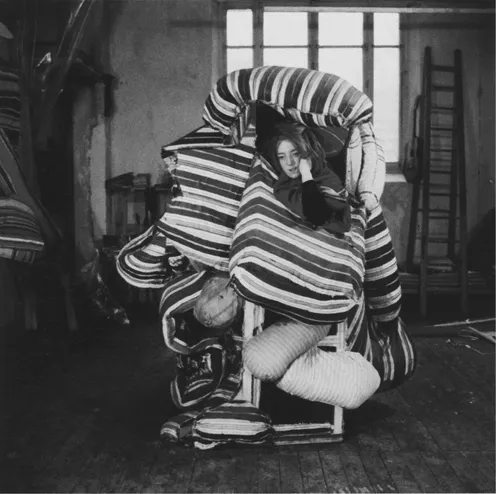

A picture taken circa 1963 at Minujín’s Rue Delambre studio in Paris again shows the artist occupying a Colchón (see Figure 2). Her body is subsumed within its swelling protuberances so that only her head, with its distinctive mop of blond hair, and an arm poke out of a window-like aperture at the top. The Colchón is covered in a repeating pattern of green and red bands, their slightly slapdash application revealing how Minujín painted the stripes directly onto the fabric. The arrangement of its bulbous sections, apparently affixed to a rectangular supporting frame, is distinctly haphazard, as if deliberately resisting coherent organization or recognizable form. When combined with the stripe-pattern, which jumps and stutters across the stuffed shapes of different sizes, the overall visual effect is, for all the Colchón’s festive air, one of slight queasiness. Although the construction in the Paris photograph could be interpreted as a mobile home, a ‘kind of mattress-house’ (Minujín 2004, 61) intended to provide comfort for a peripatetic artist, it also displays distinctly constricting and even imprisoning qualities. Indeed, the Colchones seem to infer that the transnational relocations requiring such a protective cocoon – what Nikos Paspastergiadis has influentially theorized as migration’s ‘turbulence’ (2000, 4) – might be as disorientating as they are exciting.

These performative photographs indicate that Minujín envisaged the Colchones as engulfing, even overpowering, viewers and inhabitants alike. In the Rue Delambre photograph, Minujín averts her gaze from the camera while her head rests on her arm, communicating an impression of deep and studied ennui. The inference here is that the Colchón simultaneously stands for, and occasions, the snares of self-absorption and mental confinement, while moreover constituting an analogy for the disconcerting collapse of subject into objecthood, by encircling the flesh of the occupant with sacs of wadded material. Just prior to La destrucción, Minujín held an exhibition of the Colchones she had made in Paris at her Rue Delambre studio: in the pamphlet produced to accompan...