![]()

PART 1

THE SYRO-ANATOLIAN THUGHŪR

Throughout the history of the thughūr, Islamic authors frequently refer to two geographical divisions on the frontier: the Syrian west (thughūr al-shāmīya) and the Jazīran east (thughūr al-jazarīya), with the Amanus Mountains and town of Mar‘ash as the fulcrum. These divisions are not so much geographical (typically, all lands west of the Euphrates are part of Bilad al-Sham) as military, referring to the backgrounds of the soldiers on the fronter and a two-pronged double-flank style of summer raids from the left and right (al-ṣā’ifa al-yusrā,al-ṣā’ifa al-yumnā) to the Byzantine frontier. Further, they are mentioned by some geographers, such as Istakhrī and Ibn Ḥawqal, but not others, such as Muqqadasī.1 Topographically, the frontier can be divided into three large areas, each with smaller micro-regions that are bounded by natural geographic features (Figure 3, p. 35). The western frontier, or Cilician Plain, stretches from Rough Cilicia to the Amanus Mountains. The central frontier (from the Amanus to the Euphrates River) can be subdivided into two areas: the western rift valley of the Amuq and Kahramanmaraş Plains and the eastern hilly steppe and plain of the Nahr Quwayq and Jabbūl Lake. The eastern frontier (east of the Euphrates, including the Upper Euphrates to the Tigris River) includes the Karababa, Malaṭiya, and Elazığ (Keban) Plains to the north. In presenting them, we can follow a central to east to west schematic, tracing roughly the path of interest taken by Islamic rulers in establishing permanent settlements following the conquests. By comparison, the Balikh and Khābūr Plains are examined to see how they relate to the eastern thughūr or the Jazīra. In the interest of space and focus, the Tigris region and north-east including Mawṣil, Armenia, Ādharbāyjān, and Arrān will not be included. In the manner of the Islamic geographers such as Muqaddasī, the following five sections will analyse each of these areas in turn building up the landscape from its environmental features; resources; natural passes and routes; rural settlements; tell, upland settlements and monasteries; way stations; and chief towns. Unlike Muqaddasī, a hierarchy is implied but not imposed. Rather, the main aim is to uncover what archaeological evidence exists for the thughūr and how this evidence can be used to seek out not only the historically known thughūr settlements, but the lesser-known settlements that lay in between, invisible in the texts. These elusive communities, their interactions with one another, and their use of the land are integral elements in understanding the frontier landscape.

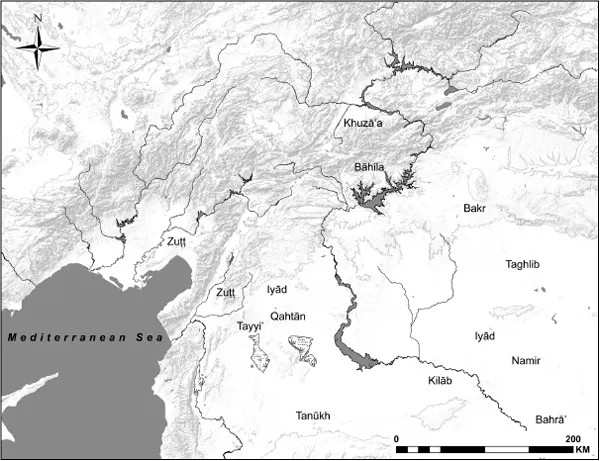

Figure 2 Tribes on the thughūr

Methodology

Surveys along the thughūr have actually been fairly well represented in publications. However, the majority of surveys before 1980 have still treated late-period sites very cursorily, giving only a limited depiction of settlement. Although a few exceptions have provided substantial detail of the Roman and post-Roman landscape, there is presently no sufficient information overall to be comparable or consistent with recent data. This is a result of targeting earlier periods for specialized research and unfamiliarity with the late-period ceramics. Recent surveys and excavations with comprehensive strategies aimed at a holistic recording of the landscape in all periods, however, such as the Amuq and Kahramanmaraş regional surveys and several Euphrates salvage surveys and Jazīra surveys, counterbalance the weaker data sets.

The primary goal of most recent surveys in the Near East is to expand on earlier tell-based surveys by variations in site type and distribution. Non-mounded sites, flat scatters in the plains, sites in upland valleys, and high-elevation plateaus are considered alongside tells. Land-use features associated with sites such as canals, roads, field terraces, presses, and mills are also recorded as part of the landscape. The landscape itself is also the subject of investigation, and newer methods utilizing geomorphology, remote sensing, and geographical information systems (GIS) help greatly in tracking changes to the environment through climatic shifts and land use over time. Surveys rely on surface collection of sites, which are susceptible to variations in visibility due to ground cover and surveyor subjectivity. Second, the main chronological indicators are unstratified ceramics from largely rural sites, which are often dominated by coarsewares in their assemblages. The trend towards localized traditions of many coarsewares and some finewares makes dating often difficult and broader, to within one or two centuries. As a result, surveys have often been regarded as secondary after excavation data, where ceramics are stratified and dating is refined by numismatic, epigraphic, and scientifically-dated evidence. However, surveys remain the only method of investigating the landscape, its settlements, and land-use patterns over time and the relationship of these to the environment. This is particularly the case for the Islamic–Byzantine frontier, for which there have been around 35 surveys and only a handful of excavations of sixth-to tenth-century sites.

Not all of these surveys can be taken at face value or compared with one another as their methods differ radically, their results are inconsistent, and their treatment of the Islamic period is general at best. Meaningful comparison and reinterpretation is required, and it reveals pertinent general information that should not discarded outright as it supports the evidence from higher-resolution Islamic-focused surveys. As a result, surveys can be divided into four main groups: (1) extensive and coarse low-resolution large-area surveys; (2) intensive and high-resolution large-area surveys; (3) extensive and fine high-resolution large-area surveys; and (4) intensive high-resolution small-area surveys around sites and with reliable dating for the Islamic periods. Surveys ranged in methodologies, and, as a result, intensive or extensive classifications are on a scale: intensive surveys typically employed walking transects and off-site investigation while extensive surveys also used vehicles and were tell-focused.2 Low-resolution and high-resolution refers specifically to the reliability of dated ceramics from the Islamic period that employ subdivisions. The coarse low-resolution surveys of the first group will be briefly described along with their general observations. The second and third groups will be analysed more comprehensively, taking into consideration the strong caveat that these high-resolution surveys had more finely tuned Islamic chronologies that allow subdivision. Recent excavations and a greater understanding of transitional and Early Islamic ceramics also permit more accurate dating of sites previously categorized by very general (at best) or incorrect chronologies. Even while this book is being written, new surveys and excavations are being conducted. Salvage excavations of rural and urban sites around the frontier carried out by Turkish museums add a significant level of information that unfortunately cannot be included in this study, as most of these are never published. Future work should add them to the larger data set. Using mainly survey data with some supplemental excavation evidence when available, these areas will be examined from an Early Islamic perspective that considers more broadly what came before and after. As labels and periods differ from survey to survey, it is necessary to configure the evidence into accepted chronologies while the original period designations will be parenthetically mentioned.

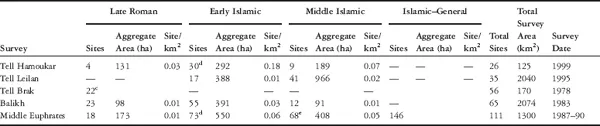

Certain trends can be detected that show general and specific Early Islamic frontier settlement patterns that are present throughout the frontier, and, at the same time, variations in micro-regions.3 Some analysis tools that have been used for other surveys with good results, such as calculating sites per square kilometer, aggregate site area per period, and site catchment areas, will not be systematically used here. Many of these surveys are not comparable on these levels. For example, the Amuq was surveyed for more than 15 years. More than 300 sites were found in an area of almost 2,000 km2, while the Nahr Quwayq was surveyed for two years in which 80 sites were found in an area of nearly 2,500 km2. Many more sites are clearly visible with remote sensing techniques. Within these areas, one survey focused on uplands as well as lowlands while the other did not. Site area calculation also represents a challenge. Many older surveys did not note site areas; however, it is possible to calculate them with the help of satellite imagery or aerial photography. Such a huge undertaking is beyond the scope of this book, but is currently being conducted in the region.4 Figuring out chronologies from such surveys still poses a problem. As such, comparing site signatures and numbers remain useful for this study. The main reason for this is that we are investigating relatively short-term changes in the landscape around settlements from the fourth to fourteenth centuries, how they are occupied, whether they continue, and, if not, when they are abandoned.

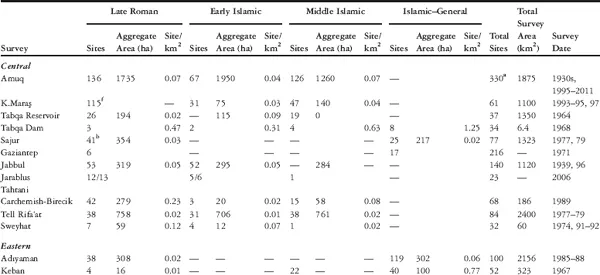

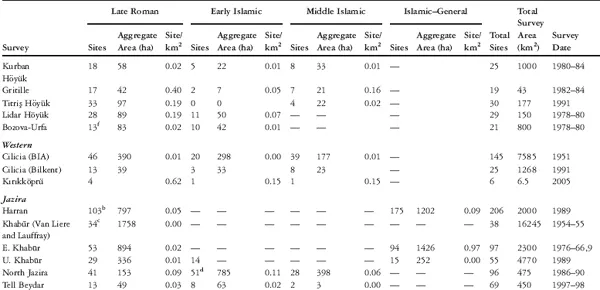

Yet, for the Islamic–Byzantine frontier, how can we refine the data futher and determine settlement patterns during the entangled, transitional sixth to eighth centuries? Or make claims as to which settlements were Islamic and which Christian? In approaching these questions, a model is applied to the Amuq and Kahramanmaraş surveys that views sites with certain criteria leaving room for nuance and degree, rather than labelling sites statically as transitional (Late Roman to Early Islamic), or one or the other (Late Roman or Early Islamic). There are discerning factors in settlement choices from the Late Roman to the Early Islamic periods resulting from human responses to environmental changes (such as marshification). These features can be linked to ethnic and cultural differences; new settlements of Muslims differed in many cases from Byzantine Christians who were already living in the plain. In order to tackle the issue of ethnic representation on the frontier, the argument initially needs to be framed in a different way. The primary element of the model differentiates the sites in terms of newly-founded de novo settlements and those that had preexisting occupations which continued. Sites with known Islamic or Late Roman pottery were ‘definite’, whereas sites with general coarsewares that were not diagnostic enough were ‘indefinite’. These criteria include arbitrary and multiple categories and subcategories of: (1) newly-founded versus preexisting settlements; (2) chronology (seventh to eighth centuries, eighth to tenth centuries, tenth to eleventh centuries, twelfth to fourteenth centuries); (3) definite versus indefinite occupation (based upon known diagnostic ceramic evidence); (4) site size (small: 1 ha and below, medium: 1.01 to 8 ha, large: over 8 ha); and (5) assemblage size (light: 1–2 sherds, moderate: 3–7 sherds, heavy: 8 + sherds).5 Survey pottery is notoriously difficult to pin down, particularly when there is no related local stratified excavation. Furthermore, pottery of the Late Roman to Early Islamic transition can also be difficult to differentiate. Definite occupation refers to the presence of at least one known diagnostic ceramic, while indefinite refers to possible ceramic presence that is ambiguously dated. The point is not to achieve total accuracy of which site was occupied where and for how long. General and even more specific trends will still arise, providing a long-term view of landscape history. For maps, a more conservative representation is given; only sites with definitive occupation are shown. Textual references to settlements – though very few for rural farms, estates, villages, and small towns – can provide useful evidence. Of course, no such archaeological model is foolproof and neither is textual evidence; settlements could and did often have mixed populations. Taken in total, these criteria can be used to develop hypothetical ethno-cultural inferences of population and demography in both a transitional period and a culturally-mixed frontier zone that are not limitations, but rather expose the rich complexity of interaction in the frontier zone (Table 1).

Table 1 Surveys on the thughūr, late period settlement6

![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE CENTRAL THUGHŪR:

THE TWO AMUQS

You will depart and alight at a meadow with ruins (marj dhī ṭulūl).1

The above quote is taken from Early Islamic eschatological texts, describing the Amuq Plain, or Plain of Antioch, as a frontier battleground for one of the final apocalyptic wars. It was also a battleground for the early conquests where Arab armies camped on al-‘Amq, the large fertile Plain of Antioch or Amuq, and chased the fleeing Byzantines. It also, however, succinctly frames how archaeologists have traditionally regarded the Amuq Plain and other similar geographic regions all over the Near East, which are dotted with tells (ṭulūl) mainly of the fourth to second millennia BCE. Indirectly, it alludes to the historical view of the frontier landscape during and following the Islamic conquests as uninhabited. Recently, close attention has been given to the non-tell landscape of the Classical, Late Antique, and medieval periods. Surveys in the Amuq and Kahramanmaraş Plains revealed a crucial series of dramatic changes that occurred in a relatively short period of time between the Late Hellenistic and Early Islamic periods. In the Late Hellenistic and Early Roman periods there was a rise in dispersed, low, mounded or flat settlements in both lowlands and uplands, and an increase in cultivation. By the Late Roman and Early Islamic periods, the seasonal wetlands had expanded into a permanent lake and marsh. The results dispel the idea of the Amuq, a historically known frontier zone, as a no man’s land, but do raise many questions as to what changes occurred in the landscape during the transitional Late Roman to Early Islamic periods. From the Late Roman to the Early Islamic period, a shift occurs that follows certain patterns of continuity, while at the same time presenting new forms of settlement and land use linked to complex factors combining landscape response and ethnic and cultural practice.

The Environment

The area of the central thughūr is bounded by the Amanus Mountains to the west, the Euphrates River to the east, Ḥalab to the south, and the Taurus Mountains to the north; a square area roughly 170 × 170 km (28,900 km2) (Figure 3). It was in reality northern Syria, considered as such by authors of the day, and topographically more Syria than Anatolia. It includes two main geographical areas, the subjects of this and the next chapter. The first area, the lowland rift-valley river-plain area in the west, is a northern extension of the Great Rift Valley connecting East Africa and the Red Sea. This valley is broken up into two discrete plains, both referred to by the same name in Islamic periods: al-‘amq, meaning the depression or lowland. The southern one is the large triangular-shaped Amuq Plain fed by four rivers, the Nahr ‘Āsī (Orontes), Nahr ‘Afrīn (‘Afrīn), Nahr al-Aswad (Kara Su), and Nahr Yaghrā (Yaghrā, no longer extant), and was dominated since the Hellenistic period by a large lake, now drained (Figure 4). The Amuq measures about 670 km2 and is indeed a low-lying depression, 90–100 meters above sea level (from here on, m.a.s.l.) receiving a relatively high amount of rainfall for the region (500–700 mm/annum). Modern Antakya receives even more, owing to its location in a narrow ravine (1,132 mm/annum) (Figure 5).

The long corridor of the Kara Su Valley connects the Amuq to the northern plain. The Kahramanmaraş Plain ...