eBook - ePub

Contesting the Arctic

Politics and Imaginaries in the Circumpolar North

This is a test

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Contesting the Arctic

Politics and Imaginaries in the Circumpolar North

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

As climate change makes the Arctic a region of key political interest, so questions of sovereignty are once more drawing international attention. The promise of new sources of mineral wealth and energy, and of new transportation routes, has seen countries expand their sovereignty claims. Increasingly, interested parties from both within and beyond the region, including states, indigenous groups, corporate organizations, and NGOs and are pursuing their visions for the Arctic. What form of political organization should prevail? Contesting the Arctic provides a map of potential governance options for the Arctic and addresses and evaluates the ways in which Arctic stakeholders throughout the region are seeking to pursue them.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Contesting the Arctic by Philip E. Steinberg,Jeremy Tasch,Hannes Gerhardt,Adam Keul,Elizabeth A. Nyman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

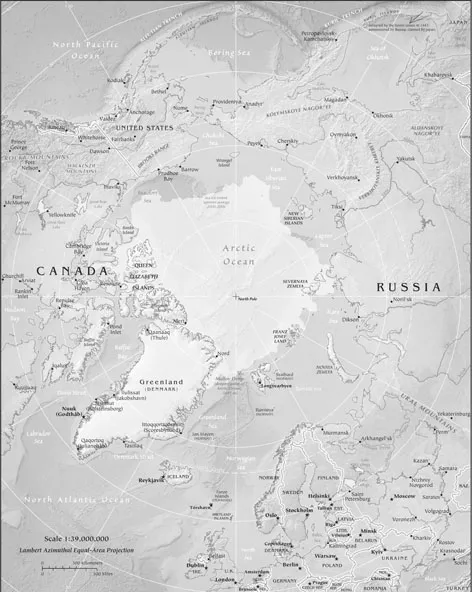

1.1 The Arctic Region.

CHAPTER 1

IMAGINING THE ARCTIC

In May 2008, representatives from the five countries bordering the Arctic Ocean met in Ilulissat, Greenland and signed a declaration that was notable in that it broke absolutely no new diplomatic or political ground. Indeed, that was the point of the declaration: to assert that there was a status quo, that it was functioning fine and that there was no need to change it.

The status quo that was reaffirmed at Ilulissat by the ‘Arctic Five’ (Canada, Denmark, Norway, Russia and the United States) was no less than the fundamental premise that underpins the political organization of the world. It is a status quo that has prevailed in Europe since at least the seventeenth century, and since then has spread through colonization and war to the rest of the world. Known as the modern state system or sometimes the Westphalian state system, in reference to the set of treaties that ended the Thirty Years War in 1648, this status quo is generally recognized as one that confers absolute sovereignty to the rulers of territorially defined states.

Although the most frequently noted aspect of the modern state system is that it divides land into state territories, it rests on an even more fundamental division of Earth’s surface that makes the state-ideal possible: a division between land, which is deemed as having the potential for territorialization (that is, division into bounded and governed territories controlled by individual states) and water, which, except for internal waters like rivers, lakes and bays, is designated as beyond state territory. In recent decades, and especially since the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) was signed in 1982, individual states have come to receive certain rights in specific zones of the ocean adjacent to their coasts. States now have exclusive rights to resources (e.g., fisheries, offshore oil deposits) out to the 200 nautical mile limits of their exclusive economic zones (EEZs) and, if certain geological and bathymetric conditions are met, these rights may be extended for the seabed minerals of their outer continental shelves out to 350 nautical miles, or, in some cases, even beyond that. Notwithstanding these limited economic provisions, however, the political status of the ocean, beyond the 12 nautical mile coastal strip of territorial water, is high seas, a global commons outside the authority of any state. There are no provisions for coastal states to extend their limited economic rights in EEZs and outer continental shelves into anything that approaches the sovereignty that they claim on land. UNCLOS thus reaffirms a fundamental division of Earth’s surface associated with the modern state system: sovereign land territories are juxtaposed against a global oceanic commons that is regulated by the state system but cannot become the territory of any individual state. Four of the five states present at the Ilulissat meeting have ratified UNCLOS and the fifth – the United States – while refusing formally to accede to the treaty, has declared that it endorses its fundamental principles as customary law.

The Ilulissat Declaration asserted that the modern organization of the world applies in the Arctic just as it does everywhere else (with, arguably, the partial exception of Antarctica). The signatories of the declaration acknowledged that the Arctic presents some unique challenges that may require extra levels of cooperation, and they expressed a desire to work with each other to address these challenges. In particular, they noted the value of the Arctic Council, a body whose working groups study and occasionally make policy recommendations regarding safety of navigation, search and rescue, environmental and development issues in the region and whose members include, in addition to the Arctic Five, the three other Arctic states (Finland, Iceland and Sweden) as well as six permanent participants representing indigenous peoples of the region. However, notwithstanding this recognition of the region’s unique characteristics and challenges, the declaration makes it clear that land in the Arctic is clearly under the control of individual states, that the ocean is a global commons to be governed according to UNCLOS, and that institutions of cooperation will be tolerated only so long as they work within, and do not seek to override, this framework.

In short, the Ilulissat Declaration is not, in itself, a particularly interesting document, since all it does is assert that the Arctic is not exceptional. What is interesting, however, is that three foreign ministers (from Denmark, Norway and Russia), a Deputy Secretary of State (from the United States) and a Minister of Natural Resources (from Canada) felt that it needed to be written at all.

Presumably, the only reason to produce a declaration asserting that the Arctic is ‘normal’ would be if someone else were suggesting otherwise. But who was this, and what were they suggesting? No ‘opposition’ is specifically named in the declaration. Four weeks after the Ilulissat meeting, members of the research team behind this book began conducting a previously scheduled series of interviews on Arctic sovereignty issues, and at the last minute we added a question to the interview guide, asking respondents what they felt the declaration was in opposition to. Although the respondents were all knowledgeable observers and makers of Arctic policy, the answers to this question were surprisingly diverse. One US government official said,

My guess is that there might be some green party in Europe that might be promoting [a treaty]. I heard some discussion of it in Scandinavia. … I’ve heard it mentioned in some European meetings, but I’ve never seen any substance.

Another American, a think-tank researcher with strong connections to the US military and foreign policy communities, asserted that the declaration was directed not at European environmentalists but at NATO, whom he was convinced had designs on the region. Still another policy professional, with a long history of involvement in international Arctic initiatives, speculated that, given Denmark’s role as lead instigator behind the meeting and that it happened in Greenland, there might have been a subtext within Danish politics concerning Denmark’s relations with its independence-seeking overseas territory.

The most complete explanation was given by an official with Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada, who contextualized the May 2008 meeting within two high-profile events that had thrust the Arctic onto the world stage during the previous summer: the brief melting of sea-ice over the length of the Northwest Passage (the potential sea route through Canada’s northern archipelago) and the planting of a titanium flag by a Russian submersible at the North Pole:

Last October [2007], there was a meeting of legal advisers in Oslo, which included an American, a Canadian, and, I don’t know who all was in the room. But it was certainly more than the five who were in Greenland. Then Denmark decided that they wanted to take this to the ministerial level. So they invited the five states which actually border on the Arctic Ocean, and they drafted a declaration which quite frankly said the same things that officials had already agreed to, which was that the Arctic is an ocean, and there is a Law of the Sea Convention which manages all aspects of the Arctic. There is simply no comparison between the Arctic and the Antarctic…. I think it was a very wise idea to get out ahead of the issue [by holding the Ilulissat meeting]. Just simply do a Google search on the Russian flag on the North Pole last summer, and you’ll see in the first instance there’s this enormous wave: ‘Here they come, Russians over the top.’ …What was being done in Ilulissat is that the five countries at the level of their foreign minsters were standing up and saying, ‘No, we’ve got a regime here, cool your jets.’… So essentially what [we were doing at Ilulissat] was getting out there and managing this issue. There’s not going to be any new regime called the Arctic Littoral States or anything like that. The foreign ministers have put down their markers, everybody’s signed on the dotted line, now we go back to work.

A similar explanation was given in 2010 by an official at the US State Department:

It would be a little bit of a misreading of the situation to say that we were enthusiastic about Ilulissat, because we were not. There was some reason to do Ilulissat, not the least of which was that it was coming on the heels of the Russian flag planting, when all the world’s media were talking about an impending war in the Arctic because the Arctic countries were all racing to claim the shelf up there, and one of the purposes of Ilulissat was to show that that is not what was happening. The second purpose that you will see in the Ilulissat Declaration is to explain that the Law of the Sea already provides sort of a framework for the Arctic, [and so] there is no need for some sort of overarching treaty that is going to govern the Arctic like the Antarctic.

An official at the US embassy in Ottawa similarly stressed that Ilulissat was less in response to anything that was actually happening but to perceptions of what was happening:

Well I don’t know that there was necessarily a specific proposal [against which Ilulissat was directed], but certainly in the media there has been a particular sense, and this goes back to global warming: ‘What will climate change portend for the future? Is it going to be this race for the North Pole? Is there going to be this Wild West atmosphere where everybody is trying to sink as many wells as quickly as they can?’ And then the Russians plant titanium-encapsulated flags, supposedly at the North Pole …. I think there is an awful lot of that in the public mind, and the media perpetuates this. It’s a story, it sells a story, you put it on the front page: ‘Canada reaffirms sovereignty in the face of Russian land-grab.’ I think maybe, and as I say I don’t know if there was necessarily a specific proposal informing anybody to do so, but even in some of the reporting in the local [Canadian] media in the run up to that meeting there was some discussion that the five countries were going to agree upon a new mechanism to control the Arctic. And from the paperwork that I saw, the documents that I saw ahead of time, that wasn’t the idea at all. The idea was that they wanted the parties to reaffirm that in fact they would settle any differences responsibly.

As the Americans’ explanations in particular make clear, the Ilulissat meeting was convened to develop a preemptive response to two, very different scenarios. Under one scenario the Arctic was emerging as a site where war could break out, as countries’ efforts to map their outer continental shelf rights would devolve into an all out ‘land-grab’ (and ‘sea-grab’). Although all individuals interviewed acknowledged that such a ‘race for the Arctic’ was not actually happening, they also recognized that the perception that such a race was occurring could lead to an actual race, and this could lead to general instability and conflict. Under the other scenario, which apparently was at least as frightening to representatives of sovereign states, perceptions that the ‘race for the Arctic’ was heating up could lend weight to calls for an Arctic treaty that would designate the Arctic Ocean as something other than an UNCLOS-governed global commons. Such a development would have the potential to undermine the near universal acceptance of UNCLOS, and theoretically it could even lead some to question core assumptions of the modern state system.

To be clear, the Arctic Five were not being irrational in issuing the declaration: one certainly could imagine a situation in which politicians in an Arctic nation were to rally their population to respond to what was perceived as another nation’s incursion into ‘our’ Arctic, and this could bring about a spiral of militarization and counter-claims. One could also imagine that amidst such tensions (and perhaps outright conflict) others would respond by calling for a comprehensive treaty in order to ‘restore the peace’. But nonetheless there is something extraordinary about sovereign states going out of their way to issue a declaration that asserts, in essence, that the Arctic is ‘normal’.

Indeed, the very existence of a declaration affirming the Arctic’s normalcy suggests that the Arctic is not completely normal. Or, if it is normal, there are enough perceptions of it being exceptional that its normalcy is contested, and therefore must be defended (and, in the process, potentially modified, whether ever so slightly as through institutions like the Arctic Council, or through more dramatic instruments). In short, preconceptions of what the Arctic is, and what it can be, matter profoundly. And this is all the more so as climate change transforms the Arctic’s underlying character and as actors involved in making, interpreting, implementing, or responding to Arctic policies determine whether the Arctic is a ‘normal’ space that follows the standards of the rest of the world or is somehow ‘exceptional’.

Imaginaries and Climate Change

A key theme in much of twentieth- and twenty-first-century social science has been to understand the links between how we experience the world, how we understand that world and how we order it (and thereby shape others’ experiences and understandings). These systems of understanding and order extend to specific spaces: both the spaces that we encounter in our everyday lives and the spaces that we attempt to understand or control from afar. In the case of the Arctic, depending on one’s perspective, the Arctic may be seen as an integral part of the existing nation-state, a sub-national indigenous group’s homeland, a lost hearth of the national soul, a resource colony that is essentially empty of humans and that exists to be exploited (whether through mining or nature tourism) or preserved, a space of everyday activities (i.e., a ‘home’), or the Arctic may be simply forgotten. As the circumstances surrounding the Ilulissat conference demonstrate, the Arctic may be seen as a ‘normal’ region or one that is ‘exceptional’. If it is ‘exceptional’, this might be because of its geophysical characteristics, as a dynamic region of ice, land and water, or it may be due to its social characteristics, distant from southern capitals and populated by historically semi-nomadic peoples who cross state borders as well as externally based resource firms that have little interest in the region’s long-term development. Or, most likely, ideas about the Arctic’s exceptionalism and normalcy stem from a combination of conceptions about both its geophysical and geopolitical properties and potentialities. These constellations of ideas about what the Arctic is, and what it can be, are what in this book we are terming imaginaries.

Imaginaries are not stable. For centuries, Europeans from outside the Arctic saw the planet’s northern periphery as a surface to cross, not a destination. The first European explorers to the North, like those throughout the Americas, sought neither territorial acquisition nor the establishment of permanent settlements. Rather, eighteenth- and nineteenth-century European explorers such as Vitus Bering, Sir John Franklin and Fridtjof Nansen were primarily driven by a desire to chart a sea route through the Arctic to the Orient. Similarly, acting on the notion that the Arctic is somehow an ‘in-between’ separating two destinations, a three-person Soviet aircrew flew an ANT-25 biplane during the summer of 1937 over the North Pole on a 7,100 mile world record setting non-stop flight between Moscow and southern California, and then back. This flight across the top of the world took place just three weeks after an earlier ANT-25 had also flown over the North Pole to reach the Pacific Northwest, to the mix of excitement and concern of Oregon residents, before the airplane’s flight crew doubled back and landed in Vancouver, Canada. To the best of our knowledge, neither crew ever considered landing at the North Pole and exploring its icy environment.

More recently, policy makers who have attempted to direct attention to the Arctic have stressed that the region is not simply an empty space to be crossed by people from distant lands but that it is an arena of connections that can bring the world together. An early proponent of this view was the Canadian–American anthropologist Vilhjalmur Stefansson, who, in such books as The Friendly Arctic and The Northward Course of Empire, argued that the Arctic, far from being a frozen wasteland, was a ‘Polar Mediterranean’. Like the Mediterranean, he wrote, the Arctic featured a relatively navigable central space that united diverse coastal peoples in commerce and productive interaction. As Stefansson wrote:

A map giving one view of the northern half of the northern world shows that the so-called Arctic Ocean is really a Mediterranean sea like those which separate Europe from Africa or North America from South America. Because of its smallness, we would do well to go back to an Elizabethan custom and call it not the Arctic Ocean but the Polar Sea or Polar Mediterranean. The map shows that most of the land in the world is in the Northern Hemisphere, that the Polar Sea is like a hub from which the continents radiate like the spokes of a wheel. The white patch shows that the part of the Polar Sea never yet navigated by ships is small when compared to the surrounding land masses.

This Mediterraneanist view of the region, which emphasizes proximate points on land rather than a separating ocean, was reproduced some 60 years later by then Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev when he noted, in 1987:

The Arctic is not only the Arctic Ocean but also … the place where the Eurasian, North American, and Asia Pacific regions meet, where the frontiers come close to one another and the interests of states … cross.

Twenty years after Gorbachev, this theme was taken up again by former Alaska governor Sarah Palin, in what was probably the most quoted moment from her unsuccessful run for vice presidency of the United States:

We have that very narrow maritime border between the United States … and Russia …. They’re very, very important to us and they are our next door neighbor …. You can actually see Russia from land here in Alaska, from an island in Alaska …. I’m giving you that perspective of how small our world is and how important it is that we work with our allies, to keep good relation[s] with all of these countries, especially Russia.

While the Arctic imaginary held by explorers searching for the Northwest Passage was of a hazardous region that, once conquered through its crossing, could then be forgotten, the Mediterraneanist imaginary is, as Stefansson would have it, a ‘friendlier’ space, one that can bring the world together. Still, even this perspective is a view from the outside. In the Mediterraneanist imaginary, the Arctic is seen as a space of connection, not separation, but it still exists primarily to connect others who live outside the region. The Arctic is therefore conceived as a land of proximate peripheries, not a center. Individuals on the islands of Little Diomede (in Alaska) and Big Diomede (two miles away, in Russia) may be able to wave at each other across their fragment of the Arctic Mediterranean, but in the visions of both Gorbachev and Palin they are located on peripheral extensions of countries whose centers are very far away.

It should be no surprise that indigenous peoples of the region have their own Arctic imaginaries, and these are quite different from those emanating fro...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- 1 Imagining the Arctic

- 2 Terra Nullius

- 3 Frozen Ocean

- 4 Indigenous Statehood

- 5 Resource Frontier

- 6 Transcendent Nationhood

- 7 Nature Reserve

- 8 Normalizing the North

- Notes

- Bibliographic Essay

- List of Illustrations