![]()

Map 1 Confessional Divisions in Europe towards the End of the Sixteenth Century

![]()

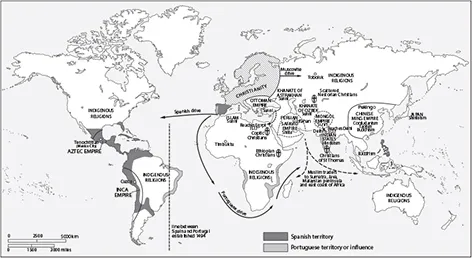

Map 2 The Global Spread of Christianity

![]()

Introduction

In 1609 the Lanark-born Scotsman William Lithgow (1582–1645) set out on a series of journeys through Europe, Africa and the Near East that would last over a decade and bring ruin to both his health and his ‘paynefull feet’. By his own reckoning he had walked twice the circumference of the earth. Lithgow was a Calvinist with few positive things to say about other views of Christianity, least of all for the ‘hissing of snakish Papists’, but he had a keen eye for religious details and in the course of his travels came into contact with a great variety of different faiths, both in Latin Christendom and the Orthodox lands in the east. Passing through France and Italy on his first journey, for instance, he took in the Catholic pilgrimage trails, sometimes with Jesuits, stopping off at Rome, Loreto and Venice, before boarding a ship for the Aegean in the company of Greeks, Slavonians, Italians, Armenians and Jews. No friend of the Greek Orthodox, he nevertheless had a high opinion of the monks of Mount Athos, who were the ‘very Emblemes of Piety and Devotion’. He was also very positive about the Maronite patriarch of Mount Lebanon, whom he considered a man of deep piety, ‘not puft with ambition, greed, and glorious apparell, like to our proud Prelats of Christendom’. In Jerusalem, where Lithgow was well treated by the local Franciscans, he lunched with French Catholics and German Lutherans, came into contact with Ethiopian Miaphysites ‘which came from Prester Jehans dominions’, and rubbed shoulders with Italians, Greeks, Armenians, Jacobites, Nestorians and numerous eastern patriarchs while visiting the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.1

Despite his close encounters with so many Christian worlds, Lithgow identified with just one strand: Scottish Calvinism. He was baptized a Scottish Presbyterian and he would die in the same faith. But not all Christians were as steadfast as Lithgow, nor were all Churches as homogenous as the Scottish Kirk. Lithgow was alive at a time when the Christian Church was experiencing radical new phases of self-examination, fragmentation and renewal, particularly in the West, where the divisions brought on by the Protestant Reformation and the Catholic Counter Reformation permanently reshaped the face of Christianity and created completely new genealogies of the faith. As a Scottish Calvinist, Lithgow himself was a product of the Reformation, even though the great religious schism had originated more than half a century before he was born. The point of origin for the rise of the Reformation is generally considered to be the year 1517, when Martin Luther, a university professor in the Saxon town of Wittenberg, posted a set of critical theses against the practice of indulgences. But many different narratives went into the making of the confessional age, each with its own myth of origins and providential scheme. And the same holds true for the sense of ending. Even during his lifetime as he walked through the lands of Protestant Europe, Lithgow came face to face with the ongoing process of Christian refashioning brought on by the Reformation. He was well acquainted with the ‘peevish and self-opiniating Puritanes’ of England, for instance, and he would have met up with many of the so-called Protestant radicals in his journeys through Germany and the Dutch Republic.

And yet for all the variety of religion in Europe, it was nothing compared to the profusion of Christianities that Lithgow encountered in the east, from the Hesychast monks of Mount Athos to the Georgian Christians in the hills of Cana and the Jacobite pilgrims in the Holy Sepulchre. Nothing in the West would have prepared the Scotsman for the polyglot, multi-confessional city of Cairo, for instance, where every conceivable type of Christian seems to have walked the streets. In his words, ‘In this Towne a Traveller may ever happily finde all these sorts of Christianes, Italians, French, Greekes, Chelfaines, Georgians, Æthiopians, Jacobines, Syrians, Armenians, Nicolaitans, Abassines, Cypriots, Slavonians, captivat Maltezes, Sicilians, Albaneses, and High Hungarians, Ragusans, and their owne Ægyptian Copties.’2 Of course, these were not new strains of Christianity; indeed, some had histories reaching back to the very origins of the faith. But many of them would have been new to Lithgow and, more to the point, all of them vouch for the diversity and the vitality of Eastern Christianity in the early modern age. For despite the fact that the majority of the Eastern Churches were subject to Muslim occupation, some communities not only survived the years of captivity and isolation but even experienced periods when their faith communities had been able to thrive.

This book is a history of the early modern Christian Church in some of its myriad earthly forms as encountered by travellers such as Lithgow. Thus it is really about Churches rather than Church, though, as one of the authors in this series has remarked in a previous volume, there is certainly enough of a ‘family resemblance’ to group them all under the general concept of Christianity.3 The period under consideration extends from 1500 to 1685, which Anglophone historians generally refer to as the early modern period, though at times the narrative will reach further back into the past than the year 1500, just as at times the analysis will take in historical issues that only really came to fruition at a later stage. But the epoch of interest – sometimes also called the confessional age – is properly framed by these two dates. And it was a period of fundamental importance in the history of Christianity, for both the Latin Church and the Orthodox Churches of the East.

Perhaps the most dramatic story to come out of this period, and in all likelihood the best-known story to readers of this book, was the schism that emerged in the Latin Church as a consequence of the Protestant Reformation. This was, of course, a profoundly creative phase in the history of Christianity, as the new Protestant religions brought an end to centuries of Universal Christendom and developed their own ideas about the nature of the Church, ‘one, holy, catholic and apostolic’, rooted in radically new theologies of salvation, communion, covenant and holy power. But it was creation at the expense of a Church that had shepherded the Christian faithful for over a millennium, and it was not without its costs. Indeed, one recent interpretation has suggested that the Reformation did not just usher in the end of the late medieval synthesis. Confessional division on the scale experienced in the early modern period, with consequences – many unforeseen and unintended – that were so far reaching and so profound, completely transformed notions of the sacred and the relationship between humankind and the divine, to the point that we might speak of the ‘eclipse’ of the ancient idea of Christendom tout court and the onset of a new age with a new way of understanding the world.4 And matters were scarcely less dramatic in the realm of Orthodox Christianity, where the ongoing expansion of the Islamic empires after the fall of Constantinople ushered in a long period of captivity for the Churches of the East.

In keeping with the spirit running through the other volumes in this series, which has set out to capture the history of the Church’s ‘innermost self through the layers of its multiple manifestations’, this book will tell the story of the early modern Church by way of different narrative strands and mixed viewpoints. On the whole, it tends to spend more time dwelling on the key episodes than uncovering the traces of the longue durée, but any history that concentrates on just one phase of the existence of something as ancient as the Christian Church necessarily sits within a much longer narrative, and without some reference to this longer narrative it is not really possible to make sense of the shorter bursts of change. So this book does try to effect a balance between the ‘innermost self’ and the ‘multiple manifestations’, even if at times it does so in a fairly idiosyncratic way.

In a similar spirit, it also tries to avoid the impression that some of these narratives are more important than others. Some very powerful words are required in order to write a history of Christianity in this period, many with heavy teleological baggage, from broad historical concepts such as Renaissance and Reformation to intricate theological terms such as transubstantiation and Filioque, but the book does not set out to privilege one particular approach over the other, nor does it want to suggest that the Church was predestined to go down a particular path. None of these histories is more existentially important than others, and not one was inevitable. Necessarily, by choosing to focus on certain strands of development, this book has a unique shape of its own, but it has tried to do justice to the complexity of Christianity in the period in the space allowed, both in the Latin and the Greek Orthodox worlds, by moving between the different modalities of the religious life, from the rarefied discourse of the theologians to the sense of covenant fostered by the emerging confessional states and the nature of popular culture in the towns and villages. Even Russia’s dancing bears get a shout.

In one sense, this book is a history of two Churches. Since the age of the first councils, the Latin Church of the West and the Orthodox Churches of the East had gone their separate ways. Divided by history, theology and the boundless space in between, the two ancient forms of Christianity had experienced little meaningful contact over the course of the Middle Ages. Indeed, one of the interesting developments of the early modern period was the West’s rediscovery of the Christian Churches of the East, some of which had customs and beliefs that seemed no less strange to Latin eyes than the customs of the inhabitants of China or Peru. On closer examination, however, this condition of Christian diversity and mutual incomprehension runs throughout the entire history of the Church in this period. It was not just the dividing line between the West and the East. Division and diversity marked out the entire age.

As a consequence, much of this history is concerned with tracing the rise of antagonistic visions of Christianity, from the first speculative soundings in the works of the humanists to the theological syntheses of the Catholic and Protestant reformers. But more to the point, this history will explore the consequences of these antagonistic visions, which, in the context of the age, were powerful enough to reshape the entire fabric of the social, cultural and political spheres. Religion influenced more than just creeds, confessions and liturgy, though these are certainly central to the story; it also had the potential to transform the secular world. Thus the historical changes brought about by religious reform are a main concern of this study, from the relations between Church and state in Germany to the effects of Puritan thought on the English social order. And it is also concerned with the attempts made to overcome these divisions, whether through councils, treaties, new notions of tolerance or the plain use of force. Above all, the history of the early modern Church is characterized by the sudden intensification of religious dialogue. In the West, it was a long-running debate about the nature of the True Church; in the East, it was a discourse about how best to preserve ancient truths in the face of changing times. Only very rarely did it end in agreement.

Some aspects of this story may seem familiar to readers with a knowledge of Christian history. The theological debates, for instance, might evoke a sense of déjà vu, so too the spirit at work in the Church, particularly in the West, where the heightened usage of biblical language, the quarrels over fine points of theology, the rise of communities of worship gathered around charismatic preachers of the Word and the mixed notes of sympathy and retribution in the wars fought by Christians in the name of God may stir up memories of prior days of the faith. Even the religious ideas might ring a bell, as early teachings resurfaced and were either imputed, or defended, by the warring prophets of the antagonistic Churches. Similarly, there was nothing new to the tensions and ongoing disagreements between Church and state about the proper spheres of the secular and the spiritual, and neither the Reformation nor the Counter Reformation invented the desire to recover the essential truths of Christianity and reshape both the Church and its believers in the image of the faith. These were all ancient themes.

But the early modern period did present the Church with fundamentally new questions, certainly in scale if not in substance. The extension of Christianity to new regions of the world, for instance, some of which were hitherto unknown, raised a series of critical issues touching on the claims of Christianity in the ever expanding world and the rights of the clergy over the indigenous souls. The spirit of reform that gripped the West led the faith in theological directions that had no precedent in the long history of the Church, and this necessarily raised questions about the authenticity of certain teachings, the truth claims of certain authorities and the means and modes of worship that should be used in order to get in a right relationship with the divine. And the fragmentation of Christian unity that followed on from the Reformation raised all sorts of issues relating to the origins of the faith, the ‘true’ history of the Church and the preservation of its past, and the extent to which the present forms of the Church and its beliefs corresponded to an orthodox ideal. For the first time since the age of the Ecumenical Councils, whole new faith-based communities emerged with contending claims to be the ‘one, holy, catholic and apostolic’, though now with the backing of the secular authorities, kings and queens included. This had profound consequences for the integrity of the faith, for as the process of confessional fragmentation took hold, defining the essence of the Church's ‘innermost self’ became that much more difficult, and that much more urgent as well. Christians, both in the West and the East, were forced to ask themselves questions about covenant, kinship and community that had not been explored so deeply, or so zealously, since the first days of the faith.

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Renaissance Christianity

Among the discoveries of the age of Renaissance was that of the Church Father Jerome. Of course, Renaissance scholars did not discover Jerome in the same sense that Columbus discovered a continent or Copernicus the workings of the solar system, but they did discover Jerome in other senses embraced by the Latin word invenire, which in addition to the cognate ‘to discover’ means ‘to find’ or ‘to come upon’. In the early modern period, scholars came upon a Jerome that was different in kind to the ascetic virtuoso of the medieval age. He retained his Christian virtues, and indeed in spades: few other Church Fathers could match his piety, austerity, wisdom, modesty and knowledge of the faith. But he began to take on other virtues as well, above all those associated with the Renaissance fascination with Greco-Roman antiquity. Jerome became a model of rhetoric and eloquence, a master of classical thought, a paradigm of moral probity, and a writer – and a reader – of otherworldly intelligence, some scholars claiming that he knew all the languages of humankind. In effect, Jerome became the patron saint of the humanist movement because it was easy to mistake him, as Coluccio Salutati once remarked, for a pagan professor.1 Yet he had remained a faithful servant of the Catholic Church; indeed, more than this, precisely because of his knowledge of ancient tongues and classical texts, as the translator of the Vulgate he was in effect a mediator between God and his Church, the man who provided Latin Christendom with Scripture.

This is what is meant by the Renaissance discovery of Jerome: on the basis of new perspectives, new philosophies and new methods of interpretation, scholars began to understand the saint in different ways. And this point holds true mutatis mutandis for the broader encounter between Renaissance humanism and Christian history. The very act of recovering the past induced a rethinking of the present. In doing this, Renaissance scholars were not consciously preparing the ground for a revolution in religious thought, nor could they have known how their labours of elucidation and explanation would be turned against the Roman Church. Nevertheless, even if unwittingly, this proved an explosive combination, for in this determination to recover the past in its pure and authentic form and use this knowledge as a guide for the present and an ideal for the future, the thinkers of the Renaissance unleashed what has been termed a ‘cultural compression’ with the potential to reshape the secular and spiritual order of the day.2 In order to understand the rise of the Reformation movement and the subsequent fragmentation of Latin Christianity over the course of the early modern period, it is necessary to begin with a survey of the efforts made by some of the most profound thinkers of the late medieval period to recover, and sometimes to discover, what they considered to be the first truths of the Christian faith.

Christian humanism from Valla to Erasmus

During the Renaissance a spirit of inquiry emerged that was devoted to the recovery of ancient Christianity. Modern scholars have referred to this spirit as the overarching impulse behind what they term ‘Christian humanism’, which itself is best conceived as an integral part of humanism in general, a phenomenon famously defined by Paul Oskar Kristeller as marked by a ‘broad concern with the study and imitation of classical antiquity’ and made up of men, primarily grammarians and rhetoricians, who were interested in recovering the pure, unfiltered ideas of both the Greco-Roman and the Judeo-Christian tradition using the hermeneutical tools they were developing within the fields of a liberal education (studia humanitatis).3 Couching their ideas in a language that approximated the eloquence and rhetorical sophistication of classical (or Ciceronian) Latin, the aim of Renaissance humanism was to recover ancient wisdom in order to effect a reform of the present age, whether in the context of the Italian city-state, the Christian community or indeed within the individual consciousness, for despite the emphasis on imitation and mimesis the humanists’ search for purity gave rise to ‘the tendency to take seriously their own personal feelings and experiences, opinions and preferences’.4

Because religion was so deeply engrained in the early modern mind, the study and imitation of antiquity necessarily took in the history of the Chur...