![]()

PART I

THEORETICAL FOUNDATIONS

![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE NATURE OF THE PROBLEM

Two neighbours may agree to drain a meadow, which they possess in common; because it is easy for them to know each other's mind; and each must perceive, that the immediate consequence of his failing in his part, is, the abandoning the whole project. But it is very difficult, and indeed impossible, that a thousand persons should agree in any such action; it being difficult for them to concert so complicated a design, and still more difficult for them to execute it; while each seeks a pretext to free himself of the trouble and expense, and would lay the whole burden on others. Political society easily remedies both these inconveniences. Magistrates find an immediate interest in the interest of any considerable part of their subjects. They need consult nobody but themselves to form any scheme for the promoting of that interest. And as the failure of any one piece in the execution is connected, though not immediately, with the failure of the whole, they prevent that failure, because they find no interest in it, either immediate or remote. Thus bridges are built; harbours opened; ramparts raised; canals formed; fleets equipped; and armies disciplined everywhere, by the care of government, which, though composed of men subject to all human infirmities, becomes, by one of the finest and most subtle inventions imaginable, a composition, which is, in some measure, exempted from all these infirmities.

David Hume, A Treatise of Human Nature,1 Book 3 Part II.8

As it was in Hume's day, collective action continues to be one of the most bewildering challenges of the twenty-first century. Often at the eleventh hour states that are bargaining fail to reach a negotiated settlement despite the existence of very compelling conditions to do so, and so leave the international community perplexed. At other times the conundrum springs from the fact that despite the existence of all-encompassing political conflicts, a negotiated settlement nevertheless occurs. At its core, the empirical puzzle this book addresses is a generic collection action problem: How do international watercourse states that share water resources develop new sets of rules or institutions to govern their shared resources? In this respect, the Euphrates/Tigris watercourse is no different than any other international watercourse in water scarce regions. But unlike some others, it has yet to see voluntary cooperation forming among its affected states to govern the entire watercourse and to address the overarching concerns over sustainable development. Indeed, the Euphrates/Tigris watercourse states have yet to even agree on a definition of their shared resource. In this and in any other case, the sustainable and efficient use of international watercourses requires collective action among the watercourse states to achieve even a rudimentary level of integrated water resource management. But such collective action – or inaction – is not always in the best interests of all states involved. This ensures that socially optimal outcomes are something that cannot be achieved either automatically or spontaneously.

To begin to understand the nature of this problem, we must first define its characteristics. In this chapter, I begin first by seeking a definition for ‘international watercourse’, a term that is at times contentious, before moving on to discuss the key concept of collective action problems, as well as the concepts of the tragedy of the commons, transaction costs, and property rights, all of which are essential for understanding conflicts over water use. The chapter ends with a summarizing parable of water rights conflicts.

What is an International Watercourse?

One of the most contentious issues in international watercourse conflicts is the definition of ‘international watercourse.’ The topic itself provokes intense debate among watercourse states, academics, bureaucrats, diplomats, and lawyers. This was especially the case during the codification process of the law on Non-navigational Uses of International Watercourses. On 8 December 1970, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution assigning the International Law Commission the task of codifying the customary principles of international law and procedural requirements for notification and consultation among watercourse states. It subsequently took 17 arduous years for the International Law Commission to draft the convention on Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses. The difficulty in reconciling competing watercourse interests could not have been more apparent, and was further revealed when the convention failed to gather first a unanimous vote of the states, and second a sufficient number of ratifications required for it to enter into force. The General Assembly adopted the convention by a vote of 103 states in favor, three states against, and 27 states abstaining (on 21 May 1997).2 All the member states of the United Nations (UN) were invited to ratify the convention by 20 May 2000. To date the convention has still not entered into force due to an insufficient number of ratifications.

The sessions of the International Law Commission provided a stage for watercourse states to play out their prickly politics. In those sessions, finding a definition of ‘international watercourse’ proved to be one of the most challenging tasks, with some states arguing that a distinction be made between an international river that forms a boundary between states and a trans-boundary river that crosses the border. Others opposed the usage of the term ‘trans-boundary river’ and suggested its removal from all the legal documents. Behind this conflict lay the competing interests of states determined, in part, by their geographic position in a watercourse. Each definition entails different rights and obligations for states. If, for example, it is defined as an ‘international watercourse’ limited territorial sovereignty claims finds support and puts upper watercourse states under the obligation to share the resource and not to cause significant harm to lower watercourse states. If, on the other hand, it is a ‘trans-boundary river,’ the absolute sovereignty of the watercourse state over the resource within its territories takes precedence limiting upper watercourse states obligations to the lower watercourse states.

Indeed, the definition of ‘international watercourse’ has been one of the prime sources of contention among the Euphrates/Tigris watercourse states. Turkey, as the upper watercourse state of the Euphrates/Tigris, makes a distinction between an international river that forms a border and a trans-boundary river that crosses the border and perceives the Euphrates and Tigris as forming a single trans-boundary water system. Therefore any water rights negotiations should include both the Euphrates and the Tigris. On the other hand, Iraq prior to the US invasion in 2003, was against the usage of the term ‘trans-boundary river,’ and in its commendation to the Draft Articles on Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses, stated that this term wherever it occurs should not be adopted. Syria's position on this issue has been equivocal, since it is a middle watercourse state of the Euphrates, the Tigris, and the Orontes watercourses. However, Syria has argued that while the Euphrates and the Tigris are international watercourses, the Orontes, which originates in Lebanon and crosses Syrian territory before reaching the Mediterranean Sea in Turkey, is not an international watercourse. The distinction is an important one and determines the legitimacy of some water rights claims.

In light of the significant debate and compromises that have informed the definition, here I use the definition of the 1997 Law of Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses. The law defines international rivers, or ‘international watercourses,’ in article 2, as follows:

An international watercourse is a watercourse parts of which is situated in different states, and ‘watercourse’ here means a system of surface waters and ground waters constituting by virtue of their physical relationship a unitary whole and normally flowing into a common terminus.3

This definition relies on a single criterion, that is, a watercourse is an international watercourse if it has parts in different states.4 The inclusion of ground waters in the definition is also notable and raises important questions about the classification of these resources. I shall return to this problem in the discussion of the differences in ground and surface water resources below.

The Nature of International Watercourses

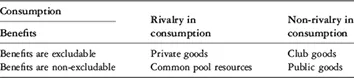

Another central issue that needs to be tackled in defining an international watercourse is the clarification of what category of goods an international watercourse falls into; this is not easily done. The goods-categorization of international watercourses has important connotations and implications for the determination of the property rights of water and for the nature and resolution of international watercourse problems (Table 1.1).

Economists identify four main categories of goods, namely public, private, club goods, and common pool resources. Rivalry/non-rivalry in consumption and excludability/non-excludability of benefits from potential users are the determining criteria by which goods are classified under one of the above-mentioned types. Accordingly, private goods are subject to rivalry in consumption and the benefits are easily excludable; public goods, on the other hand, are not subject to a similar rivalry in consumption and the benefits are non-excludable. Club goods refer to goods that are not subject to rivalry in consumption, but the benefits are excludable. Lastly, common pool resources, or commons, refer to goods for which there is a rivalry in consumption and the benefits are not excludable. These are ideal types and most goods fall somewhere on the two dimensional continuum with varying degrees of excludability and rivalry. Among the common pool resources that have received significant scholarly attention are fisheries, forests, wildlife, ground and surface water resources, irrigation systems, land tenure and use, and global commons including climate change, air pollution, and international watercourses.

Table 1.1. Classification of Goods.

The literature dealing with water scarcity and conflicts variously classifies international watercourses under the categories of private goods, public goods, and common pool resources. This has important implications for the suggested solutions to our main problem. As result, the oppositions between the different classifications of international watercourses, for example, public goods versus private goods versus common pool resources, comes to the fore as an issue of contestation in the literature, which will be dealt with in the coming sections. Table 1.1 shows that the main distinguishing characteristics of public goods are non-excludability and non-rivalry in consumption. Water as a commodity does not carry both of these characteristics. Yet, it has long been treated as a public good and a free commodity. For now, suffice it to say that the tradition of treating water as a public good by both states and the public presents challenges to states, since the uninterrupted provision of water is expected to be provided by a state. The idea of treating water as a private good is unacceptable to many societies. Indeed, water is often provided by the state free of charge or with a minimum charge to the public.5

Common pool resources or commons, on the other hand, require more scrutiny here because international watercourses carry some of the same characteristics and are subject to the same perils as are the common resources. Common pool resources are defined as ‘natural or man-made resource systems that are large enough to make the exclusion of potential users from obtaining benefits from its use prohibitively costly, and the benefits obtained from its consumption by one individual user are sub-tractable from those available to other potential users.’6 Since benefits are not excludable and someone's consumption is another's loss in common pool resources situations, the over-exploitation of resources to the extent of a resource's devastation becomes likely. International watercourses have some of these specific characteristics. For instance, it is difficult for a watercourse state to deny legitimately the benefits that are obtained from the development of water resources to other watercourse states, whether they have contributed or not to projects like dams, which regulate a river's flow and prevent flooding. This is a classical example of positive externalities or spillovers. Alternatively, pollution affects all watercourse states, but not equally. Indeed, lower watercourse states could bear the costs of pollution disproportionately. The nature of international watercourses is such that upper watercourse states could rationally choose actions with negative spillover effects imposing costs on other users while fully benefiting from the resource and vice versa. The cost–benefit analysis for an individual state though rational could be the wrong for the entire watercourse. Though it is virtually impossible to cut river flow running into lower watercourse states, upper watercourse states could significantly alter the nature of the resource. Moreover, the rivalry in consumption of international waters is nowhere more apparent than in the arid and semi-arid regions. Due to sequential access, appropriation and usage in international watercourses have close resemblance to private goods. International watercourses then are impure common pool resources with strong private good characteristics.

This situation with international watercourses fairly represents the underlying tension between collective and individual rationality, between the interests of the entire watercourse and its parts divided among different states. It is better for the users, be it individuals or states, of common pool resources to take particular actions, but these actions are not always in the best interests of some users. So how do users coordinate their actions and design institutions specifying their rights and duties with respect to their common resources? Here then coordination over common resources becomes a collective action problem.

Collective Action Problems

Political philosophers have long recognized the problem of collective action within the context of the subversive incentive structure of common resources. One of the earliest accounts of this problem, in fact, dates to the fourth century BC. In Politics, Aristotle observed that what is common to the greatest number has the least care bestowed upon it.7 Indeed, few are surprised when we read about current overfishing, overexploitation of groundwater aquifers, or air pollution, for example. Often, the incentives created by an open-access or non-property regime are to blame and the suggested solutions range from regulation by governments to privatization, and include voluntary self-government by the users. We can categorize such proposed solutions into three groups: hierarchical, market-based, and community based solutions. In hierarchical solutions a pre-existing structure, such as the state or a group leader, imposes order; in market solutions a price mechanism enables collective action by reducing cost and increasing benefits; in community-based solutions common values and knowledge play an important role. In what follows, I briefly trace and discuss the intellectual origins of each of these solutions in order to illustrate the diversity of collective action problems. For our purposes, this illustration underscores the need for a multipronged, rather than simply an either-or approach to locating a solution to the collective action problem of international watercourses.

There has long been tension between hierarchical, market-based, and community based solutions. Earlier literature was frequently marked by the presumption that collective action solutions must be provided by the state. The intellectual origins of this disposition go back to at least the seventeenth century. Writing during the English Civil War (1648–51), Thomas Hobbes argued that a Leviathan, a commonwealth or state with an authority to restrict individuals’ unrestricted pursuit of self interest, was needed in order for there to be social order.8 He famously described the causes of disorder and the dire results of an absence of central authority:

[S]o that in the nature of man, we find three principal causes of quarrel. First, competition; secondly, diffidence; thirdly, glory […] Hereby it is manifest that during the time men live without a common power to keep them all in awe, they are in that condition which is called war; and such a war as is of every man against every man […] In such condition there is no place for industry, because the fruit thereof is uncertain; and consequently no culture of the earth; no navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by sea; no commodious building; no instruments of moving and removing such things as require much force; no knowledge of the face of the earth; no account of time; no arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.

Hobbes, Leviathan, Ch. XIII

Though Hobbes captured the primal need for central authority, it was Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–78) who gave a more accurate presentation of collective action problems in his story of a group of stag hunters. If the hunters coordinate their actions and cooperate they could catch a stag, which could feed all of them and more.9 If one of the hunters defects and goes after a hare, he could only feed himself and the rest will go hungry. The defector will receive a higher payoff regardless of what the others do, but all the hunters will be better off if they cooperate. This gives the hunters strong incentive to cooperate, unless they believe one of the other players will defect. More recent commentators on this type of si...