![]()

Part 1

The Conqueror

The long reign of Hammurabi, some 43 years, saw a profound transformation in the Babylon that his father had bequeathed to him. From a mediocre power, land-locked in a Near East dominated by a few superpowers, Hammurabi created a kingdom, exerting supremacy over the whole of Mesopotamia. Now a new synthesis of this history can be attempted, based on the considerable influx of new information which has been published in the last 20 years and which derives in particular from the very rich archives of Mari.

His reign can be divided into four phases. Insofar as concerns the kingdom of Babylon the first 18 years are still rather poorly known. They seem obscured under the shadow of the vast kingdom which covered the whole of the north of Mesopotamia, from the middle reaches of the Tigris to the middle reaches of the Euphrates, created by the great Samsi-Addu of Ekallatum. The second phase opened up with the death of Samsi-Addu (1775), when there was an attempt by the king of Ešnunna to reclaim his heritage. He failed in this attempt and Hammurabi, fighting together with the emperor of Elam and the troops from Mari, contributed to his downfall. But once the Elamites had annexed Ešnunna, they wanted Babylon to submit as well, but Hammurabi, with the support of his Syrian allies, managed to repulse them in 1764. What followed was a brief but successful phase of his reign in which Hammurabi launched political offensives in all directions. It culminated in the capture of Larsa in 1763, and then in 1761 of Mari, which was destroyed several months later. The final ten years of his reign was a period of consolidation of his previous conquests.

INTRODUCTION

The Relationship between the Historian and the Sources

To place him in a wider historical context, Hammurabi compelled the world of his time to recognise Babylon as a superpower in the Near East. But to appreciate this fact it is important to present the sources which have made it possible to reconstruct the events of this period. The traditional aim of historical research has been to narrate the past as elegantly as possible. Any allusions to the documentary sections of the dossier compiled by the researcher have had to be unobtrusive. But in recent years a more clinical and frank approach has become acceptable, in which it has become obligatory for the historian to show readers the documentation available. However skilfully an investigation may be conducted, it may suffer from the inevitable limitations imposed by the documentation, particularly when we are dealing with material from so long ago. The art of good scholarship lies in being able to surmount these obstacles, while openly acknowledging their existence. These problems are primarily associated with the significance of writing within the social and cultural practices of a given period, but also with the risks involved in the conservation process itself.

The Nature of the Sources

All the sources available for writing a history of the reign of Hammurabi are a result of the efforts of archaeologists, which is also true for writing any general history of Mesopotamia. The discovery of primary material has the great advantage of being unlikely to be as biased as a later, traditional narration of events would have been. But even though we now have access to contemporary epigraphical material, original texts written on materials such as stone, metal and especially clay, interpreting them presents a plethora of obstacles. The Mesopotamian documents about Hammurabi at our disposal can in general be described as basic, for we have no narrative history or more sophisticated description of events. There is no ancient biographer or even a chronicler of his reign. No-one undertook to string together isolated occurrences into a progressive story. For that matter, neither do we have any comprehensive description of the institutions of ancient Babylon. There is no Babylonian counterpart to Thucydides or Titus Livy. We have to imagine trying to reconstruct the development of the institutions of ancient Greece just from the surviving decrees, without any recourse to the Constitutions collected by Aristotle and his pupils. Mesopotamian archaeologists have to survive with no traveller and geographer such as Pausanias (second century AD) as their guide. They have no narrative of an itinerary offering a description of visits to sites. It is as though they had to solve a giant jigsaw puzzle unsure of the overall picture or whether they had the right number of pieces.

A historian of Classical Antiquity is accustomed to categorising sources as epigraphical documents or literary texts. These literary texts were repeatedly copied, from the period of Late Antiquity until the end of the Middle Ages, sometimes through the intermediation of Byzantine and Arab sources, and particularly through the efforts of those working in the scriptoria of Western monasteries. At long last they appeared in print through skills acquired from the technical advances of the Renaissance. But, as for texts of the pre-Classical period from the ancient Near East, it is only the Bible that has been the object of such an unbroken tradition.

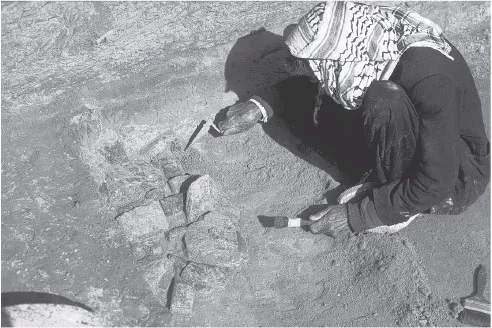

The difficulties associated with dealing with epigraphical material should not be overlooked. The researcher is always at the mercy of whatever the excavator happens to find, and experience has shown that archaeological discoveries are most often achieved not by rational planning, but by a succession of fortunate coincidences. André Parrot, for example, began excavating the palace of Mari (Tell Hariri) in Syria, not very far from the border with Iraq, in 1933. But it was bedouin, who happened to unearth an ancient statue while digging a family grave, that led him to start work there. The discovery of the archives that came from his excavations there have provided an abundance of information about the life and times of Hammurabi. On more than one occasion a government’s decision to construct a dam was the impetus for an archaeological rescue dig. It was better to recover at least something of what was concealed on a site before allowing it to be submerged forever. Of course there have been excavations that have been undertaken with advance planning and are properly programmed, but they are rare by comparison. One such excavation was the remarkable investigation of the Diyala valley, to the east of Baghdad, undertaken by Americans in the interwar years. Instead of just concentrating on Ešnunna (Tell Asmar), the main town of the region, they were able to establish what was happening in the whole region.

Sometimes the first results of a dig seem to have been clearly inadequate from some perspectives, but the discovery and publication of new texts can help to correct some deficiencies. The archives from the palace of Mari have enabled us to fill in a great many details of the middle years of the reign of Hammurabi of Babylon, the years coinciding with those of the last sovereign of Mari, Zimri-Lim (1775–1762). But unfortunately we have no similar material with which to reconstruct precise details of the events at the beginning of his reign. It is also important to remember that we can place these Mari documents into a particular archaeological context, which is not always the case. It is never without significance to know the different literary genres found at one particular location. What is most deplorable is that clandestine digging has had such a ravaging effect and has so often has robbed us of crucial information. Documents frequently arrive on the market deprived of their archaeological context and even of details about the site where they were found. They are then randomly scattered all over the world to be incorporated into private and public collections. This illicit activity still continues apace, and whatever the legal and moral questions it raises we must highlight the fact that it produces an irreparable loss of information.

The archival documents on which we rely for our information frequently have the drawback of being terse in style. In sale contracts there is never any statement to say why some patch of ground is being sold or the purpose for which the purchaser is acquiring it. Letters provide us with much information and, although they are less stereotyped, they are sometimes very difficult to understand. Background details are not always explicitly stated, for these were perfectly well known to sender and addressee alike. All too often the allusions in them give only a vague idea of what is implied.

The normal way in which Babylonians wrote to one another was to use the cuneiform script imprinted on a clay tablet. Clay had the advantage of being easily accessible, even though it took some time while it was carefully worked, cleaned, shaped and made ready for writing. The written document was put out in the sun to dry and to make it durable. There are certainly considerable advantages in such a durable medium, not all of which could have been foreseen when it was being used. An outbreak of fire, provided it is not too violent, serves to increase its durability, and flood water does not cause lasting damage. A tablet discovered in damp surroundings can be put out to dry immediately after it is excavated and the information recorded on it is preserved. Hardly any other medium in the history of writing has been so tough and so cheap, but a clay tablet is not very versatile and poses some restrictions in communication. A correct estimate had to be made for size when shaping the tablet so that the text to be inscribed would fit. This must have been particularly difficult for a scribe to whom a letter was being dictated. Any correction could be made only at the time of writing, while the clay was moist, and once it had dried no changes would have been possible. When a document became obsolete it was easily recycled by soaking the hardened clay and kneading it again into shape. We are probably often dealing with archives written on recycled clay. Usually the tablets that were kept in an archive date only to the period immediately before the building in which they were stored was destroyed, and all earlier documents have become lost. But, fortunately for the historian, obsolete texts were sometimes thrown away, and often a very useful archive can be reconstituted from discarded tablets which were used by ancient builders as filling during renovation work. A high level of archaeological and epigraphic expertise is required to recover and process such material.

The script in which Akkadian was written consists of a series of wedge-shaped signs. It is known as ‘cuneiform’, a name derived from the Latin word cuneus (‘wedge’). The signs were impressed upon the surface of a clay tablet with a stylus made from a reed. Differently angled wedges were combined to form specific signs. The script was probably invented for writing Sumerian and the earliest evidence for it can be dated to the end of the fourth millennium. Sumerian does not seem to be related to any other known written language and died out as a spoken language towards the end of the third millennium. But for more than 2,000 years it was used in religious and scholarly circles. It must have had a status similar to that of Latin in Western mediaeval and modern civilisation.

Fig. 1 When a new floor of pounded earth was being laid in the temple of Šamaš at Larsa (Tell Senkereh) tablets dating from the time of Hammurabi were used as material for ballast. Here they are being delicately excavated.

By stages, from the second half of the third millennium onwards, Akkadian, a member of the large family of Semitic languages, the best known of which are Hebrew and Arabic, replaced Sumerian. From around 2,000, two branches of the language can be distinguished, Assyrian in the north and Babylonian in the south. When writing Akkadian, two different techniques are combined. Some cuneiform signs function as whole words, the ‘ideograms’, and others indicate just a syllable of a word, the ‘syllabograms’. This leads to a measure of superfluity, and it has been calculated that the language could have been adequately written with about 80 syllabograms. Old Babylonian documents use about 120 signs. Disregarding very rare signs, there are about 50 ideograms that occur with varying frequency according to the genre of text being written. Obviously it was not the easiest script to learn, but it would be easy for those of us used to the alphabet to exaggerate this difficulty. Several members of the ruling class could read and write, but they would normally have had professional scribes in their service, who unavoidably act as a screen, intermediaries for the modern historian of their versions of ancient events. They reveal only as much information as they have filtered out, and when reading their versions this aspect of their writing should not be forgotten.

The invasions of the Amorites began in about 2000 and from then onwards there were significant modifications to the population of central and southern Mesopotamia. Although as yet we have no single text in Amorite, the extent of their influence can be seen from the frequent attestation of people with Amorite personal names. In the regions to the north and north-east of Mesopotamia Hurrian was spoken, and we find a number of Hurrian names as well as a letter and some incantations written in Hurrian in this period.

More often than not a cuneiform document is discovered as a clay tablet in a poor state of preservation. It cannot be published until much meticulous work has been done by a trained epigraphist on the unclear traces of the signs. Usually supplementary information has to be adduced from elsewhere for this task to reach a satisfactory conclusion. If the tablet has been broken, piecing together the fragments that remain can be a frustrating puzzle in itself and any attempt to restore the text of lacunae is fraught with uncertainty. But even when a satisfactory text has been established, the translator faces other kinds of problems. Despite the wide range of Akkadian literature now at our disposal, a newly discovered text will often contain rare words which raise philological problems. It is not unusual for the meaning of such words to remain imprecise or doubtful. Over the course of time documents will need to be re-edited, not only because subsequent closer examinations of the tablets, usually referred to as ‘collations’, establish better readings, but also because proposals for corrections to the original publication and a revised translation arise from the later discovery of related documents. For example, there were about 1,300 letters from the royal archives of Mari published between 1936 and 1993, but now, thanks to J.-M. Durand, new translations of them with commentaries are available.1

While it is clear that a historian of Ancient Babylonia needs to become competent in both epigraphy and philology, we must also be aware that history cannot be properly written from documents alone, for there are other sources of information available which can and must be used. Many Assyriologists have developed the habit of referring to iconographic examples simply to illustrate an allusion in a text. They have left the language of iconography encrypted and not allowed the images to speak on their own terms. It is true that we do not have so many bas-reliefs, stelae or statues sculpted in the round but we do have a number of clay figurines and many cylinder seals, which together provide a wide range of iconographic material. Understanding the language of iconography is far from easy, as can be seen from the uncertain significance of the common motif of the ring and the rod in the hands of a god who is being addressed by the king. Other questions such as this still have to be answered adequately.

The monuments unearthed from archaeological excavations have an intrinsic importance for the historian who wishes to understand the civilisation of Ancient Mesopotamia. Without reference to the structure of a palace it would be impossible to reach a full understanding of the nature of royal power, but this involves more than an architectural description. To assign a date to the end of a known level of occupation is also possible with archaeological evidence of destruction and this can be important for understanding events about which the texts are silent. Archaeological surveys over a wider region are also important in this connection. Mapping the surface finds of pottery from all the recognisable sites in a particular area can produce a reasonably precise pattern of sedentary occupation. When the information gleaned in this way is combined with what can be deduced from texts we are able to establish the beginnings of a historical geography. This is how the location of some sites was fixed well before any excavation began there. Research based on regional surveys has also been able to identify ancient waterways, which were different from those of today. An important task of such research has been to trace the courses of the Tigris and the Euphrates in the second millennium BC.

Combining information from texts with that from non-written sources is far from easy, but if it should happen that different types of evidence complement one another, that is a particularly precious occasion for the historian. Usually references to events in texts cannot be observed from the archaeological record and, conversely, texts will be silent about objects and phenomena discovered by archaeology.

COMMEMORATIVE TEXTS

It is convenient to classify the texts available to us as commemorative, archival or pedagogic documents. Commemorative texts include royal inscriptions, laudatory hymns and lists of year names.

Year Names

The simplest way to identify a par...