1 ARBITRARY OBJECTS

During the same year that ‘Modernist Painting’ was first published in the Voice of America’s Forum Lectures, the exhibition Sixteen Americans was being held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Organised by the Curator of Museum Collections, Dorothy Miller, the show intended to survey the currency of American art and included the work of Ellsworth Kelly, Louise Nevelson and Jasper Johns. Miller also decided to exhibit the work of Frank Stella, after having visited his studio with the art dealer Leo Castelli. Stella’s contribution was four large-scale paintings that had been systematically executed in black enamel paint on unprimed cotton duck canvas using a two and a half inch house painter’s brush. Within the exhibition catalogue, alongside a photograph of the besuited 24-year-old, was the following statement, penned by the artist Carl Andre:

As Thierry de Duve points out, at this moment ‘Carl Andre’s Preface to Stripe Painting appears utterly Greenbergian. It shares the same ontological assertion that painting is defined by its minimal, formal, and material “necessities” or conditions, which exclude any symbolic subject matter.’3 But for all of what ostensibly appeared to be a shared agenda, Greenberg’s ‘Modernist Painting’ and Andre’s statement were representative of two quite distinct impulses within the broader context of modernist painting. For whilst Greenberg’s text and for that matter his criticism generally at that time were organised around a qualitative set of aesthetic judgments that were historical in their orientation and origin, Stella’s practice sought to repudiate painting being critically framed this way and the essentially humanist reading it implied. After this point, Greenberg would direct his attention towards the ‘post-painterly abstractionists,’ the name he gave to those artists who he considered were the rightful heirs to formalism following Abstract Expressionism’s demise.4 In contrast, the austere, pared-down and obdurate materiality that characterised Stella’s paintings at the time became understood, by some at least, as directly anticipating the subsequent development of Minimalism.

Despite Stella’s paintings being seen in these terms, the movement itself was notable for the general paucity of painting that was directly produced in its name. This was partly due to the fact that many artists who were directly associated with it, and indeed, had begun their careers as painters, were trying to negotiate a critical position for their work that fell beyond the historically received understanding of art as being organised around a series of discrete disciplines or media, an understanding that underpinned Greenberg’s approach to art criticism. Whereas Greenberg privileged medium specificity within his reading of the artwork, Donald Judd, an artist who would become Minimalism’s unofficial spokesperson, wrote in 1965 that: ‘Half of the best new work in the last few years has been neither painting nor sculpture.’5

However, whilst no painters became directly associated with Minimalism per se, there remained a number of artists who brought a similar attitude and set of ambitions to painting. As Douglas Crimp notes, ‘… it was precisely those moves made by Minimal sculpture and its dematerialized offshoots which invested painting with both a renewed aspiration for anti-illusionism and the strategies with which to pursue it’.6

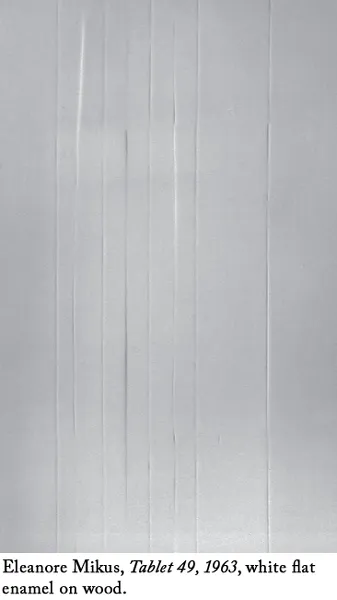

In marked contrast to the more overwrought tendencies with which at least some of their Abstract Expressionist forebears had become associated, the essentially monochromatic paintings of Jo Baer, Robert Ryman, Eleanore Mikus and Agnes Martin sought to present an account of painting that was notable for its apparent lack of incident and overt detail. Notwithstanding the subtle but important differences between their paintings, at the time all paid close scrutiny to the delimitation of what were considered to be, in effect, a number of painting’s material givens. These included its actual or literal surface, its outermost edges and the facture that resulted from a particular application of paint.

Whilst the work that they were producing during the first half of the decade appeared to rehearse Greenberg’s own assertions with regard to modernist painting, it would be erroneous to interpret stylistic affinities with conceptual ones. For example, although Eleanore Mikus’s ostensibly blank paintings appeared to be very close to the white monochromes of Ryman, in terms of the rationales that were informing their respective practices, fundamental differences remained.

Mikus had moved from Rahway in New Jersey to New York in 1960, having an address first on Eighty-Eighth Street in New York City and then subsequently moving to a loft studio at 76 Jefferson. In 1962 two of her Tablet paintings, Tablets 2 and 6, were shown in a group exhibition at the Mortimer Brandt Gallery in New York.

The Tablet paintings were the result of an extended and iterative process that began with the artist bracing together a number of irregularly sized sections of wood. This formed the basis for the painting’s support which was sanded and then applied with several layers of white gesso, a process which, according to the artist, took anything between ‘six weeks to a couple of years to complete.’7

Whilst their pared-down, physical appearance was broadly comparable with the unembellished and somewhat austere aesthetic of Minimalism (although the movement itself was very much in its infancy), the Tablet paintings remained somewhat out of step with both Minimalism and aesthetic formalism. Instead, they remained closer in sensibility to Robert Rauschenberg’s white monochrome paintings that the artist began in 1951 and that were first exhibited two years later at the Stable Gallery in New York. Certainly, both sets of paintings eschewed any straightforward determination of authorial presence. Indeed, beyond being indicative of the fact that his ideas ran counter to those of the Bauhaus artist Joseph Albers, his teacher at Black Mountain College, Rauschenberg’s claim that his practice ‘was just an attitude about materials that was strong enough not to submit to Albers’ dictum of “It’s the man who does the painting …”’ verbally articulated what the white monochrome paintings visually espoused, namely the tendentious withdrawal of authorship.8 Equally, rather than wanting to impose onto her work an individuated series of marks that would denote artistic identity as, arguably, certain Abstract Expressionists had attempted to do, Mikus spoke of wanting to capture a quality in her Tablet paintings that was akin to the worn surface of a turnstile.9

Whilst, then, it could be argued that the somewhat anonymous appearance of both Rauschenberg’s monochromes and Mikus’s Tablets antedated Minimalism’s own depersonalisation of the artwork, where they arguably differed was with regard to the ideas that informed their respective practices. For example, whilst Rauschenberg along with John Cage were exploring ideas around Zen Buddhism, Mikus’s predilection for worn surfaces was due to the particular resonances they could educe. Equally, whilst the approach to picture making by Mikus appeared to have a certain sympathy with Greenberg’s own essentialising claims on behalf of the artwork, what worked against the Tablet paintings becoming assimilated within the more dominant discourses centring upon the status and condition of the modernist artwork was their somewhat equivocal status and willingness to open themselves up to a more associative if not visually poetic, set of readings.

For Greenberg, such essentialising claims centred upon the mobilisation of painting towards that which was considered to be unique to itself. As the critic had claimed two years after ‘Modernist Painting’ had been published, ‘… the irreducible essence ...