![]()

PART I

FUNCTIONS FOR SALE

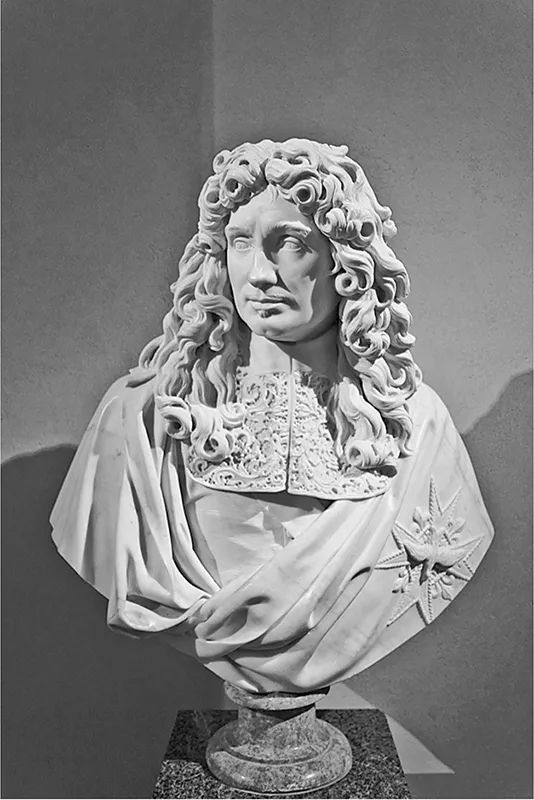

Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1619–1683) by Antoine Coysevox

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Colbert and the Sale of Offices

When in the later Middle Ages kings began to realise that they could no longer wage war effectively by raising feudal levies, they were compelled to look for unprecedented sums instead to fund professional warriors. They realised at the same time that they would never be able to find the necessary sums through taxation alone. Soon seeing themselves as overtaxed, their subjects resisted their demands either by evasion or simply by refusing to pay; and states lacked the means of assessment and compulsion to back up their demands, especially among their richest subjects who found means to avoid at least the majority of direct taxes. Great orders or corporate bodies, such as the church or the nobility, soon proved able to formulate excellent reasons for exemption that no king was able to set aside. Above all, the liquid wealth of mercantile groups completely escaped fiscal demands.

These were the problems that gave rise to the sale of offices. By selling public offices, in other words farming out portions of the royal authority to persons prepared to pay for it, kings found a way of persuading holders of liquid capital to place it in their hands. Nor was it only their own capital. Office-holders themselves could borrow more on the security of their offices; and by varying the powers and privileges attached to them, a king could find further occasions to make their holders borrow and pay out.

And so in the sixteenth century the sale and manipulation of offices became widespread in European monarchies. It was found in the Spanish Empire and the states of the Pope, in England, and in several German principalities.1 But nowhere was venality more widespread or more systematically exploited than in France. It was already well established when, in the 1520s, King Francis I set up the Office of Parts Casual (bureau des parties casuelles) to serve, in the famous words of the jurist Loyseau, ‘as a stall for selling this new merchandise’.

Given that, ever since 1467, an office was defined as a function of which no holder could be deprived except by death, resignation, or forfeiture, it was the soundest of investments. Very soon, most of the king’s offices were venalised, and their number never ceased to multiply. Entire new categories of offices were created simply for selling, without the slightest regard for sound administration. Between 1515 and 1610, their number rose from around 4–5,000 to about 25,000, most of them judicial offices. The advantages attached to venal offices reached their peak in 1604 with the introduction of the Paulette or annual due (its official name, usually shortened to annuel) which guaranteed the free transmission of an office to a named successor, heir, or buyer in return for the payment of a fee worth one sixth of its official valuation (finance). This protected the officer from the operation of the so-called forty-day rule (introduced in the 1530s) under which, if an officer happened to die within 40 days of relinquishing an office, it reverted to the king or, as the phrase went, ‘fell to the Parts Casual’. The only worry office-holders might still have was over the renewal of the annuel, which was normally only granted for a period of nine years. The king might always choose not to renew it, which would upset the matrimonial strategies of thousands of families whose property and fortunes were bound up in offices. Almost inevitably, therefore, any renewal by the king offered him the chance to demand extra payments from officers in order to retain the privileges of ‘admission’ to the payment of the annuel.

French society and institutions in the seventeenth century were deeply marked by the development of venality. Office purchase became the main ladder of social mobility for the elites, and several thousand ennobling offices at the summit of the system opened nobility to the ambitions of the richest commoners. The body of office-holders made up a powerful network of interests, and each company fiercely protected its corner of the system. At the same time, the king came to depend more and more on venality. His ‘casual’ revenues, essentially what venality brought in, made up an important proportion of the royal finances. In the year when Richelieu entered the Thirty Years’ War, casual revenues made up no less than 40 per cent of the king’s income.2 And, since the alienation of royal authority represented by the sale of an office was never more than temporary, capital advanced in this way could never be considered more than a loan. The king could not suppress an office without reimbursing the holder. And so, despite repeated promises by monarchs and regents throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries to abolish venality, reimburse office-holders, and recruit servants of the state on merit, it was never seriously possible to think of such a policy because of its prohibitive cost. It is probable that the point of no return in this process had already been reached as early as the reign of Henry II (1547–1559), when the renewal of Italian wars brought renewed expansion of venality.3 The creation under Henry IV of the annuel marked in turn a recognition of the fact that it was better to milk systematically a system which could not be got rid of. This approach reached its peak under Richelieu who, while deploring the principle of venality, realised the practical impossibility of doing without it, and exploited it to its very limits.

It was under the ministry of Richelieu that Jean-Baptiste Colbert entered the circles of power. He did so in 1640 when his father bought for him the office of commissioner for war (commissaire des guerres). He passed some time at the beginning of his career in the office of François Sabathier, Treasurer of the Parts Casual,4 thus learning very early on how the venal system worked, not to mention the operations of the great state financiers and the dangers brought on by their bankruptcies (like that of Sabathier himself in 1641) for the stability of the crown’s finances.5 Later, as a clerk to Secretary of State Michel Le Tellier, and his link-man to Mazarin, he found himself at the centre of the state’s affairs at the time of the crisis which led to the Fronde. Notoriously, the Fronde began with a revolt of office-holders. Triggered by new financial demands prior to the renewal of the annuel in April 1648, the Fronde quickly developed into a protest movement, led by the magistrates of the Parlement of Paris, against the suspension of interest payments (gages) attached to offices, against new office creations, against the extortionate demands of the traitants or partisans who managed the market in offices, and against the loss of jurisdiction by courts made up of venal officers in favour of non-venal commissioners in the form of the intendants. Colbert, by then a Counsellor of State and so close to the centre of power, was able to observe how this resistance imperilled the kingdom’s war effort, and finally plunged it into civil war. The latter in turn almost destroyed the career of this man on the rise when, in 1651, Mazarin, the patron to whom he had sworn loyalty, was driven into exile. Colbert was reduced simply to managing the affairs of the absent cardinal. These experiences seem to have determined his attitude towards officers in general, and the whole system of venality.

Although the defeat of the Fronde and the uncontested return of Mazarin to power brought a renewal of many of the ‘innovations’ condemned by the magistrates of the parlementary Fronde (gages in arrear, return of intendants, renewed reliance on traitants and partisans) Mazarin did not stubbornly carry on as if nothing had happened. It was true that the war, which as before continued to drive the exploitation of venality, continued until 1659, but the creation of new offices slowed markedly and when the annuel was renewed in 1657 there were no new conditions or financial demands. In this Mazarin followed the advice of Fouquet, who as procurator-general of the parlement thought himself best placed to manage it, and as Superintendant of the Finances sought to persuade the court not to impede new financial edicts necessary for the final resolution of the Spanish war.6

But already Colbert did not like Fouquet’s approach. He thought there was nothing to be gained by protecting the interests of office-holders, at whatever level.7 When in the autumn of 1659 Mazarin asked his opinion on the state of the finances, Colbert condemned the short-term expedients so far favoured by the Superintendant. And although, like the Frondeurs of 1648, he advised the setting up of a special Chamber of Justice to make traitants pay back their excessive and illicit profits, that was the only way in which his ideas matched those of the office-holders and chimed in with their interests. For Colbert, the essential corollary of diminishing the power of traitants was to reduce at the same time the privilege of office-holders, whose exploitation offered the financiers so many of their so-called ‘extraordinary affairs’. He advised starting by cutting the gages and fiscal privileges of ten thousand officers in the Bureaux of Finances, and minor financial jurisdictions like the élections and the salt stores (greniers à sel). Then the number of offices themselves could be cut.

To this end [he wrote] we might take away their annual due, diminish their gages and rights, and order the price of one or two offices of every sort on a footing of the last one sold, in each generality or election, always beginning by reimbursing the youngest; by so doing, with justice to all, we might bring down all these offices over the time of 3 or 4 years to the tenth part of the number of officers living on what they draw from the people, raising the number of those subject to the taille who would be the richest and would give the people more means of paying their taxes. The king would also derive an infinitely more considerable advantage than that, which is that more than 20000 men who lived throughout the kingdom by means of these great abuses which have slipped into the finances, will be obliged to apply themselves to trade and to manufactures, to agriculture and to war, which are the only occupations which render the kingdom flourishing.8

After that it would be possible to

work at the reduction of the multiplicity of officers of sovereign and subordinate jurisdictions, of the abuses committed in justice, and to have it dispensed to the people more promptly and at less cost, it being certain that officers of justice draw from the people of the realm every year, by an infinity of means, more than 20 millions of pounds which there would be much justice in diminishing by more than three quarters, which would render the people more comfortable and would leave them more means to provide for the expenses of the state; and further, there being more than 30000 men living from justice in the whole extent of the kingdom, if it were reduced to the point where it ought to be, 7 or 8000 at the most would be sufficient, and the rest would be obliged to employ themselves in commerce, in agriculture or in warfare, and they would work in consequence to the advantage and the good of the kingdom, instead of only working as at present to its destruction. Should his Eminence so desire, notes can be sent to him of all these increases in officers of justice which have been made for 50 or 60 years, and the means that could be employed to reduce them, without risk of any outcry ...9

Mazarin took no notice of this suggestion; but the memorandum of Colbert clearly shows a first sketch of several ideas which would drive his policies once the cardinal had disappeared and Fouquet was eliminated, with the agreement of the young Louis XIV.

Louis XIV certainly had his own reasons for mistrusting office-holders. He had not forgotten, nor ever would, the humiliating treatment he had received at their hands during the Fronde. He blamed rebellious magistrates for launching this movement, ‘parlements still in possession of and relishing usurped authority’.10 At the same time he deplored ‘offices filled by chance and by money, rather than by choice and by merit; the inexperience of some judges, lacking in knowledge; rules on age and length of service evaded almost everywhere’.11 He concluded that ‘reform was necessary. My affairs were not i...